Imagine closing your eyes and knowing that every memory you have ever formed is safe somewhere beyond your fragile brain. The smell of your childhood home after rain, the face of someone you loved and lost, the first time fear tightened your chest, the quiet pride of surviving something difficult. All of it preserved, searchable, replayable. Not as stories told by others, not as faded photographs, but as living experiences stored in a digital cloud. The idea feels like science fiction, yet it also feels uncomfortably close. As technology pushes deeper into the brain and deeper into data storage, the question no longer sounds absurd. What if we could upload our memories to a cloud?

This question is not merely about technology. It touches the deepest parts of what it means to be human. Memory is not just information; it is identity, emotion, continuity, and meaning. To imagine memories leaving the brain and living elsewhere is to imagine ourselves becoming something new. The idea promises immortality and healing, but it also threatens privacy, authenticity, and even the definition of self. To explore this possibility honestly, we must walk carefully between scientific reality and emotional truth.

What a Memory Really Is

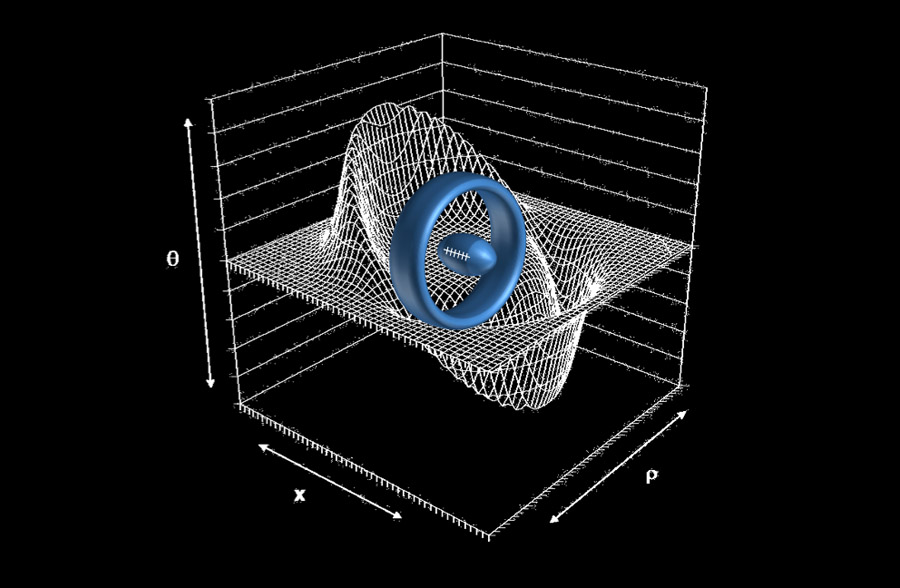

Before asking whether memories can be uploaded, we must understand what a memory actually is. In the brain, memory is not a single object or file that can be neatly extracted. It is a living process created by networks of neurons communicating through electrical signals and chemical changes. When you remember something, specific patterns of neural activity reappear. These patterns are shaped by synaptic connections that strengthen or weaken over time.

Memories are distributed rather than centralized. A single experience may involve sensory regions, emotional centers, language areas, and motor systems all at once. The memory of a loved one’s voice involves sound-processing circuits, emotional associations, and contextual understanding. There is no single “memory cell” to capture and upload. Memory is more like a living ecosystem than a static archive.

Even more importantly, memories are not fixed recordings. Each time you recall a memory, it changes slightly. Emotions shift, details blur or sharpen, and new meanings attach themselves. Memory is creative, not merely reproductive. This biological truth complicates the dream of uploading memories. We are not dealing with files, but with dynamic, evolving patterns deeply embedded in a living brain.

The Science of Reading the Brain

Despite this complexity, neuroscience has made astonishing progress in reading aspects of brain activity. Brain imaging technologies can now identify patterns associated with certain thoughts, images, or sensations. Researchers can sometimes reconstruct rough images a person has seen by analyzing activity in visual areas of the brain. Neural implants can record signals from neurons and translate them into commands, allowing paralyzed individuals to move robotic limbs or type with their thoughts.

These achievements suggest that at least parts of memory-related activity can be detected and interpreted. The brain speaks in electrical and chemical signals, and technology is learning to listen. However, listening is not the same as understanding. Capturing the full richness of a memory would require reading not only which neurons fire, but how strongly, in what timing, and in what context. It would require mapping the brain at an almost unimaginably detailed level.

This is not just a technical challenge but a conceptual one. Memory exists within a living system that is constantly changing. Uploading memories would mean freezing something that is inherently fluid, or continuously updating it as the brain evolves. The science does not forbid this in principle, but it places it far beyond anything currently achievable.

The Dream of a Memory Cloud

The idea of a memory cloud borrows from modern digital life. We already store photos, messages, documents, and videos online. These digital memories extend our biological memory, allowing us to remember more than our brains alone can hold. Uploading memories feels like the next step in this trajectory, replacing external records with internal experiences.

In this imagined future, memories could be accessed instantly. You could relive moments with perfect clarity, share experiences with others, or preserve your inner life for future generations. The cloud would become a vault of human experience, a collective archive of consciousness.

Emotionally, this dream is powerful. It promises an escape from forgetting, from the erosion of time. For those facing neurodegenerative diseases, it suggests a way to preserve identity when the brain begins to fail. For those grieving loss, it offers a chance to hold on more tightly to what matters most.

Memory, Emotion, and the Body

Yet memory is not just neural data. It is inseparable from the body. Emotions arise from interactions between the brain and bodily systems, including hormones, heart rate, and sensory feedback. Fear is not just a thought; it is a racing pulse and tightened muscles. Joy is warmth, lightness, and expansion.

When you remember an emotional event, your body responds. This bodily component shapes the meaning of memory. Uploading memories would require capturing not only neural patterns but the bodily context that gives them emotional depth. A memory without its bodily resonance may feel hollow, like a photograph without color.

This raises a profound question. If a memory is replayed outside the body, is it still the same memory? Or does it become a simulation, accurate in detail but lacking the visceral presence that makes it truly personal? Science suggests that memory and embodiment are deeply linked, making full separation difficult if not impossible.

The Question of Identity

Perhaps the most unsettling implication of uploading memories concerns identity. We tend to think of ourselves as continuous beings moving through time. Memory is the thread that holds this continuity together. It allows us to say “I” and mean the same person yesterday and today.

If memories are stored in a cloud, who owns them? If they can be copied, shared, or edited, what happens to personal identity? If someone else experiences your memories, are they experiencing a part of you? If your memories exist independently of your brain, do you still need your brain to be yourself?

These questions are not merely philosophical. They strike at the core of legal and ethical systems built around individual identity. If memories can be duplicated, individuality becomes less clear. If memories can outlive the body, the boundary between life and death blurs.

The Illusion of Digital Immortality

One of the strongest emotional drivers behind memory uploading is the promise of immortality. If your memories survive, perhaps some part of you survives as well. Loved ones could revisit your thoughts, your experiences, your inner voice. It sounds comforting, almost sacred.

But scientifically, memories alone do not constitute a living mind. Consciousness is not simply a collection of memories. It is an ongoing process involving perception, decision-making, emotion, and self-awareness. Memories without consciousness are records, not experiences.

A cloud of memories would not feel alive. It would not wake up, wonder, or choose. It would not suffer or hope. It would be a mirror, not a mind. While such a mirror could be deeply meaningful, it would not be you in the way you experience yourself now.

The Fragility of Truth

Another challenge lies in the reliability of memory itself. Human memory is famously imperfect. It distorts, embellishes, and forgets. These flaws are not bugs; they are features shaped by evolution. Memory prioritizes meaning over accuracy, helping us adapt rather than record.

Uploading memories might create the illusion of perfect recall, but what would be uploaded? The original experience, or the brain’s current reconstruction of it? If memories change with each recall, the uploaded version may reflect the present self rather than the past reality.

This raises ethical concerns. A memory cloud could become a powerful tool for manipulation. Edited memories could reshape identity. False memories could be preserved and reinforced. The line between truth and narrative would blur even further.

Privacy in the Age of Inner Data

If memories could be uploaded, privacy would face an unprecedented challenge. Memories contain secrets not only about ourselves but about others. They reveal vulnerabilities, desires, fears, and mistakes. Once digitized, such information becomes vulnerable to misuse.

Even with strong security, the risk of unauthorized access would be enormous. A memory breach would be more than a data leak; it would be a violation of the self. Unlike a password, memories cannot be changed easily. The damage would be deeply personal and irreversible.

Scientific accuracy demands acknowledging that any digital system is vulnerable. No storage method is perfectly secure. The idea of placing the most intimate aspects of human life into such systems raises questions that technology alone cannot answer.

Healing and the Hope of Memory Control

Despite these dangers, the potential benefits are significant. Memory uploading could transform medicine. Traumatic memories could be studied, modified, or safely stored outside the brain. People with memory loss could retrieve parts of their past. Neurological conditions could be better understood through detailed memory mapping.

From a scientific perspective, understanding memory at the level required for uploading would represent an extraordinary leap in neuroscience. It would deepen our knowledge of how experience becomes identity. It could lead to therapies that restore memory, reduce suffering, and enhance learning.

Emotionally, the hope of healing is compelling. For those haunted by painful memories or losing themselves to disease, the idea of preserving or reshaping memory feels like mercy.

The Boundary Between Human and Machine

Uploading memories would blur the boundary between biological and digital existence. Humans would become partly informational beings, with parts of their inner lives existing outside their bodies. This shift would challenge long-standing intuitions about what is natural.

Science shows that humans already rely on tools to extend themselves. Writing extends memory. Glasses extend vision. Computers extend calculation. Memory uploading would be an extension of this trend, but at a far more intimate level.

The emotional response to this possibility is mixed. Some feel excitement at the expansion of human capability. Others feel unease at the loss of something sacred. Both reactions are understandable, reflecting the tension between progress and preservation.

Time, Memory, and Meaning

Memory shapes our experience of time. It allows us to learn from the past and imagine the future. It gives life narrative structure. Without memory, moments lose context and meaning.

If memories could be accessed instantly and endlessly, our relationship with time might change. The past could become ever-present, reducing the natural fading that allows healing and growth. Forgetting, often seen as a weakness, plays a crucial role in emotional balance.

Science recognizes that forgetting is adaptive. It prevents overload and allows focus on what matters now. A memory cloud that never forgets might overwhelm rather than enrich, trapping individuals in endless replay.

Consciousness Cannot Be Uploaded So Easily

A crucial scientific distinction must be made between memory and consciousness. Consciousness is not a thing stored in one place. It emerges from dynamic interactions across the brain and body. Uploading memories does not automatically upload consciousness.

Some imagine that if enough memories are stored, consciousness will somehow emerge. Current scientific understanding does not support this. Consciousness appears to require real-time interaction with a living system. A static archive of memories, no matter how detailed, would not spontaneously become aware.

This does not diminish the emotional value of memory preservation, but it clarifies its limits. A memory cloud would be a powerful record, not a living continuation of the self.

The Ethics of Remembering Forever

Ethical questions surround not only privacy but consent and control. Who decides which memories are uploaded? Can memories be deleted? Can they be inherited? Can someone be forced to upload or prevented from doing so?

Science can describe what is possible, but ethics must guide what is acceptable. A world where memories can be extracted and stored would require entirely new moral frameworks. The potential for abuse would be significant if safeguards were weak.

Emotionally, the idea of losing control over one’s memories is terrifying. Memories are where we hide and where we reveal ourselves. Protecting that space is essential to human dignity.

The Value of Forgetting

There is quiet wisdom in forgetting. It allows wounds to soften and identities to evolve. It creates space for forgiveness, reinvention, and peace. A technology that preserves every memory risks undermining this natural process.

Scientific research shows that memory consolidation and forgetting are linked. The brain actively prunes memories to maintain flexibility. Total recall is not a sign of intelligence or health. It can be a burden.

A memory cloud that offers perfect preservation might change how people live, making them more cautious, less spontaneous, more trapped by their past selves. The emotional cost of such permanence deserves serious consideration.

A Mirror Held Up to Humanity

The question of uploading memories ultimately reflects our deepest hopes and fears. We fear loss, death, and forgetting. We hope for meaning, connection, and continuity. Technology becomes the canvas onto which we project these desires.

Scientifically, the road to memory uploading is long and uncertain. The brain’s complexity, the embodied nature of memory, and the limits of current technology make full memory uploading a distant possibility. Emotionally, however, the idea already influences how we think about ourselves.

By imagining memory clouds, we are really asking what parts of ourselves matter most. Is it information, or experience? Is it continuity, or growth? Is it preservation, or change?

The Future as a Question, Not an Answer

Whether or not memory uploading ever becomes possible, the question itself is valuable. It forces us to confront what memory means, what identity means, and what kind of future we want to build.

Science teaches us that not everything that can be imagined should be pursued without reflection. Emotional wisdom reminds us that progress must honor human values, not just technical capability.

If we ever stand at the threshold of uploading our memories to a cloud, the decision will not be purely scientific. It will be deeply human. It will ask us not just what we can do, but who we want to be.

Holding On Without Letting Go

In the end, memory is precious because it is fragile. It gains meaning from its impermanence. Moments matter because they pass. People matter because they change and eventually leave us.

A cloud of memories might preserve images and sensations, but it cannot replace living presence. Science can help us remember, but it cannot teach us how to let go.

Perhaps the most honest answer to the question is this: even if we could upload our memories, we would still need to live, to forget, to feel, and to become. Technology may one day hold our memories, but it will never fully hold our humanity.