For nearly a century, the Big Bang theory has been the reigning champion of cosmic origin stories. It tells us that the universe, all 93 billion light-years of it, burst forth from a singular, unimaginably hot and dense point approximately 13.8 billion years ago. From this cosmic fireball came space, time, matter, energy—everything. Galaxies unfurled like fireworks, stars ignited, and planets coalesced. Eventually, we arrived: tiny humans on a blue rock, asking how it all began.

But what if that story isn’t the whole story? What if the Big Bang wasn’t the beginning at all?

The question may seem heretical, like daring to rewrite Genesis after millennia of tradition. Yet in physics, heresy often leads to revolution. As our instruments reach farther into the universe and our equations probe deeper into the heart of time, some physicists are beginning to consider a remarkable possibility: that the Big Bang was not the origin, but a transition—a dramatic chapter in a much longer cosmic narrative.

A Beginning Without a Before

The Big Bang theory, despite its explosive name, does not actually describe the beginning of everything. It starts at the moment the universe becomes hot and dense enough to leave observable traces. Everything before that is shrouded in mathematical ambiguity and theoretical haze. The phrase “before the Big Bang” sounds paradoxical, like asking what’s north of the North Pole. Time itself, the theory suggests, came into existence with the Big Bang. If time did not exist before that, then how can there even be a “before”?

But this view rests on the assumption that time must have a beginning—a hard edge, a moment of absolute origination. This assumption, while elegant, may not be necessary. Increasingly, physicists and cosmologists are exploring models where time does not begin at the Big Bang, but flows through it, much like a river flowing through a waterfall. The waterfall is dramatic, even transformational—but the water existed before, and continues after.

These ideas aren’t fringe science fiction. They’re grounded in real mathematics, rooted in serious attempts to reconcile general relativity—the theory of gravity—with quantum mechanics, which governs the subatomic realm. At the heart of this effort lies a tantalizing challenge: to understand what space and time really are, and whether they have a beginning at all.

The Quantum Curtain Before the Bang

Peering backward in time, physicists confront a wall. General relativity predicts that as we approach the Big Bang, density and temperature shoot toward infinity. But infinities in physics are signs that something is breaking down. They’re not answers; they’re warning signs. Just as a camera loses focus when zoomed too far, our current theories blur at the Big Bang.

To see past this cosmic curtain, we need a theory that marries the smooth, geometric elegance of Einstein’s space-time with the jittery unpredictability of quantum particles. One candidate is quantum gravity—not a single theory, but a category that includes ideas like loop quantum gravity, string theory, and causal set theory.

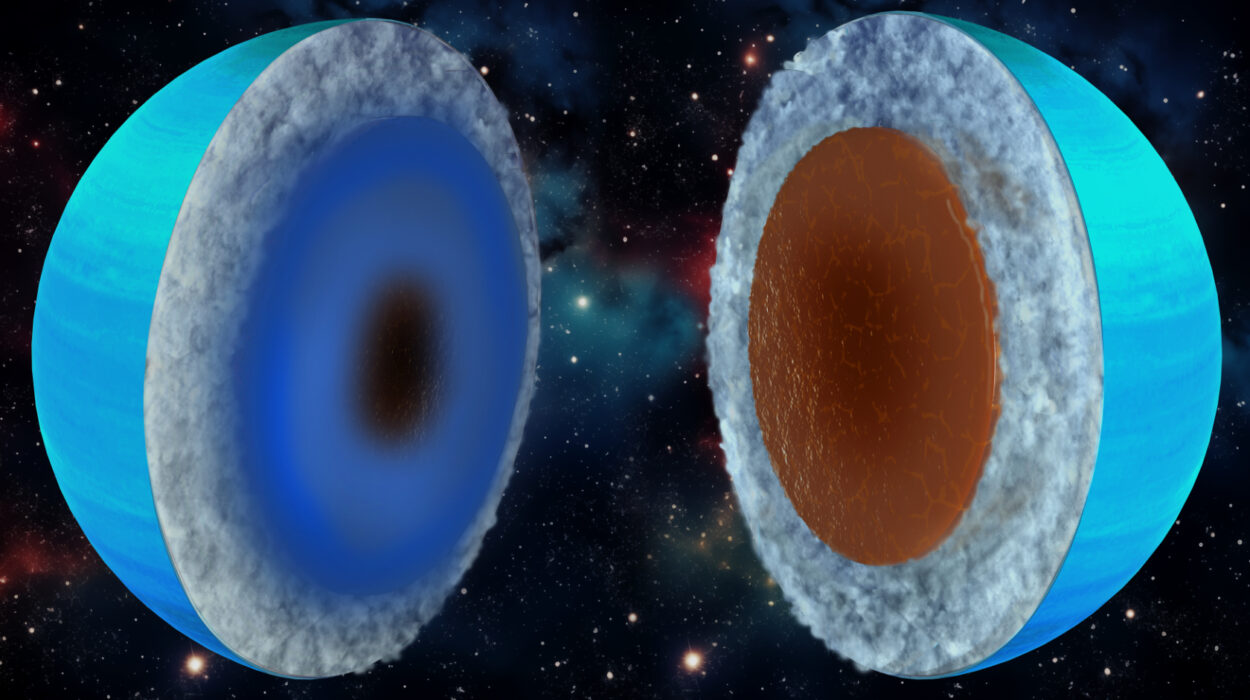

Loop quantum gravity, for instance, proposes that space and time are not continuous but made of tiny loops, like woven threads of a fabric. In this model, the universe doesn’t begin with a singularity. Instead, there is a “quantum bounce.” The universe may have been contracting before the Big Bang, growing denser and hotter, until quantum effects caused it to rebound, expanding into what we now call our universe.

In this picture, the Big Bang becomes a bounce point—a turning of the tide. The universe existed before, perhaps in a contracting phase, and will continue afterward, possibly expanding forever or cycling through new bounces. This is not a birth from nothing, but a reconfiguration of something eternal.

The Echoes of Eternity

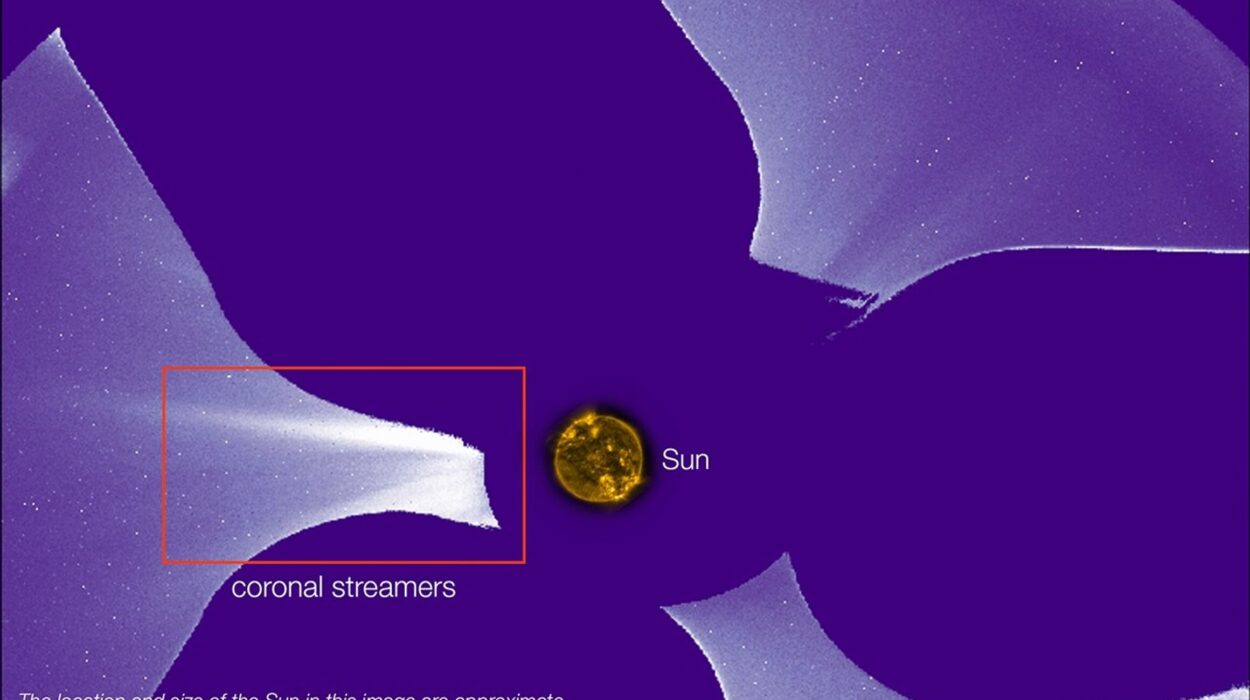

If the Big Bang was a bounce, could we detect echoes of a previous universe? Physicists have turned their eyes to the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—the faint afterglow of the Big Bang—looking for subtle patterns that might betray events from a time before time.

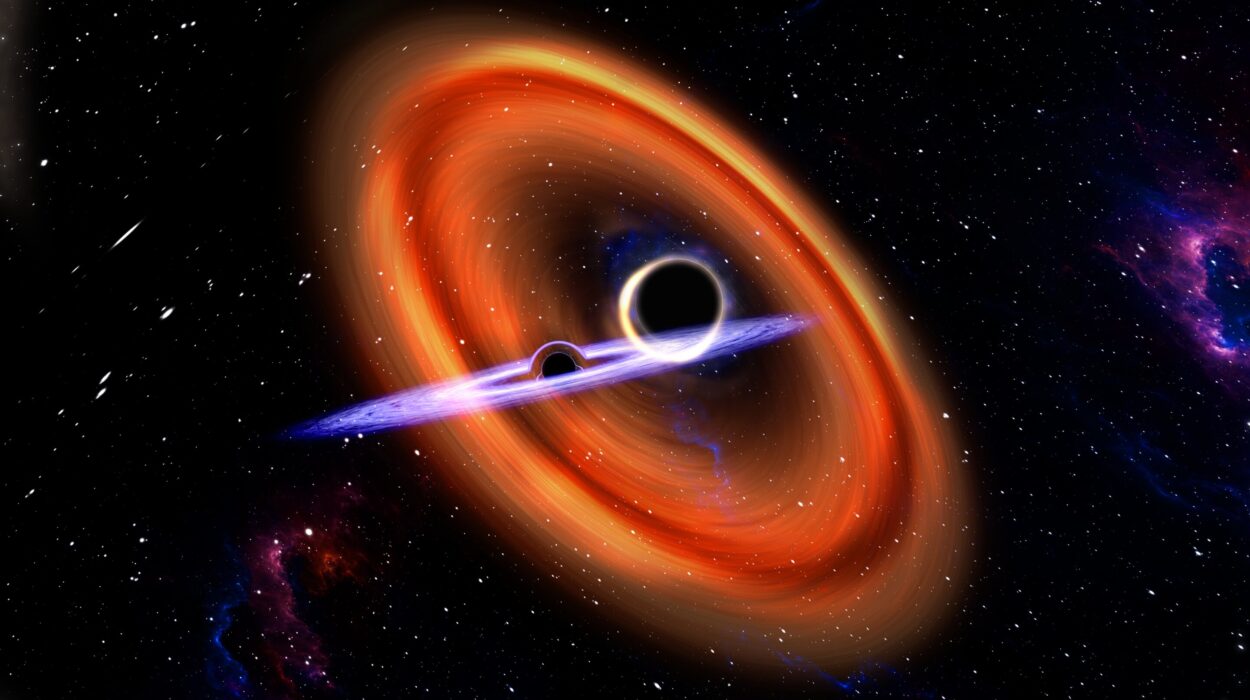

Some researchers, like Roger Penrose, suggest that certain circular imprints in the CMB might be “Hawking points”—the death-throes of black holes from a prior cosmos. In his theory, called conformal cyclic cosmology, the universe repeats in endless cycles of expansion and decay. Each eon ends in a kind of fading whisper, which somehow sets the stage for a new beginning.

Others hunt for signs of asymmetry, irregularities in temperature, or specific anomalies in the CMB that standard inflationary models don’t predict. So far, nothing conclusive has emerged—but the possibility that relics of a past universe could be imprinted in our sky is both scientifically thrilling and existentially profound.

Time as an Illusion?

As we stretch the boundaries of what “before” the Big Bang might mean, we’re forced to grapple with a deeper question: is time even real?

According to some interpretations of quantum mechanics and theories of quantum gravity, time might not be a fundamental property of the universe. It could be emergent—a byproduct of change, rather than a backdrop in which change occurs. In such models, the concept of a “beginning” becomes slippery, like trying to find the first note in a symphony where the instruments gradually fade in.

Theories like Julian Barbour’s timeless universe propose that what we perceive as time is just a sequence of configurations—like pages in a flipbook. There’s no “flow” of time, only a structure of possible moments. From this perspective, the Big Bang isn’t a starting point but a configuration among others, with no special status except that we happen to be able to observe its aftermath.

If time itself is an emergent phenomenon, then the question of what came “before” the Big Bang might be as meaningless as asking what color silence is.

The Multiverse Maze

Another avenue of thought opens an even more mind-bending door: the possibility of a multiverse. In this framework, our universe is just one bubble in a vast, perhaps infinite, cosmic foam. Big Bangs could be common events—like firecrackers popping in an endless festival of creation.

Some multiverse models arise from inflationary cosmology, which suggests that in the first trillionth of a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang, space underwent an exponential expansion. If this inflation continues in other regions, it could spawn new universes with different physical laws, disconnected from our own.

Other models stem from string theory, which requires extra dimensions and multiple solutions to its equations—each corresponding to a different universe with its own set of particles and forces.

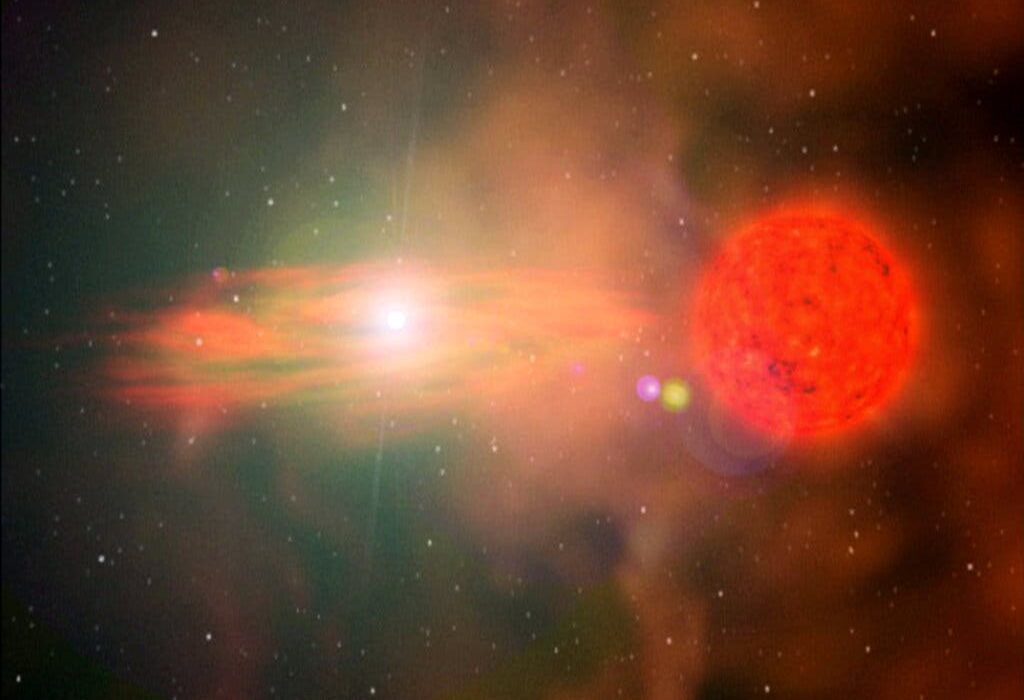

In these scenarios, the Big Bang is not the beginning, but a beginning—a local event in a vastly larger and more complex cosmic architecture. It could be that our universe emerged from a black hole in another universe. Or perhaps our Big Bang was a collision between two higher-dimensional “branes,” like cymbals crashing in a dark orchestra beyond our perception.

These ideas remain speculative, but they are not fantasies. They arise naturally from attempts to understand the fundamental equations that govern reality.

The Philosophy of a Pre-Big Bang Cosmos

The idea that the Big Bang wasn’t the beginning is more than a scientific hypothesis—it’s a philosophical pivot. It shifts our existential footing. For centuries, we’ve asked, “Why is there something rather than nothing?” The Big Bang gave us a partial answer, but if the Bang itself came from something, then we must ask: what kind of reality has no beginning? What kind of universe just is?

In classical theology, the question of origin pointed toward God. In modern cosmology, it might point toward laws, patterns, or structures that exist outside our familiar notions of space and time. Perhaps these meta-laws are eternal, spawning universes like sparks from a flint. Or perhaps the universe is a self-contained loop, its beginning and end meeting like the head and tail of an ouroboros.

Some philosophers argue that existence may not require a cause. That the need for a first cause is a projection of human psychology, not a logical necessity. Others, like the philosopher David Deutsch, see the multiverse as the ultimate explanation: all possible realities exist, and we inhabit one branch of this infinite tree.

Whatever the answer, rejecting the Big Bang as the absolute beginning forces us to grapple with questions that lie at the edge of science, logic, and mystery.

Cosmic Humility and the Future of Origins

If there’s one lesson from considering a pre-Big Bang universe, it’s humility. For all our technological prowess and mathematical wizardry, we are still peering through a fogged window at a vast, ancient reality. Every time we think we’ve reached the foundation, the ground gives way to something deeper.

But that’s also the beauty of science. It’s not a collection of final answers, but a process of perpetual questioning. When Einstein revolutionized physics in the early 20th century, he upended centuries of Newtonian certainty. When quantum mechanics emerged, it shattered our classical intuitions. The idea that the Big Bang wasn’t the beginning could be the next such revolution—a paradigm shift that forces us to reframe not only how the universe began, but what it means for anything to begin at all.

New telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope and future gravitational wave detectors may eventually offer clues. We may find ripples from before the Big Bang, signals encoded in ancient light, or mathematical insights that allow us to bypass the singularity entirely.

Or we may discover that some questions have no definitive answers—only deeper questions. The quest to understand the beginning may become a journey without end.

Epilogue: The Poetry of Pre-Existence

Suppose the Big Bang wasn’t the first breath of existence, but merely a breath in a cosmic song with many verses. That thought doesn’t diminish its importance; it enriches it. Our universe, with its galaxies and black holes and living beings, becomes part of a larger story—one that stretches beyond time as we know it.

Whether we emerged from a bounce, a brane collision, or a prior universe that crumbled into rebirth, the miracle of our existence remains. We are matter that thinks, stardust that contemplates the stars. We are the universe becoming aware of itself, not just as it is, but as it was—and perhaps, as it always has been.

In the end, asking what came before the Big Bang is not just a scientific question. It is a poetic one. It invites us to imagine the unimaginable, to grasp for the infinite, and to find wonder not only in the answers but in the act of asking.