At the heart of every cell in your body lies a hungry demand for energy. Whether you’re sprinting across a soccer field or simply reading a book, your body is constantly converting food into fuel. This energy largely comes from glucose—commonly known as blood sugar. It is the primary currency of energy, absorbed from your meals and delivered by the bloodstream to tissues that require it.

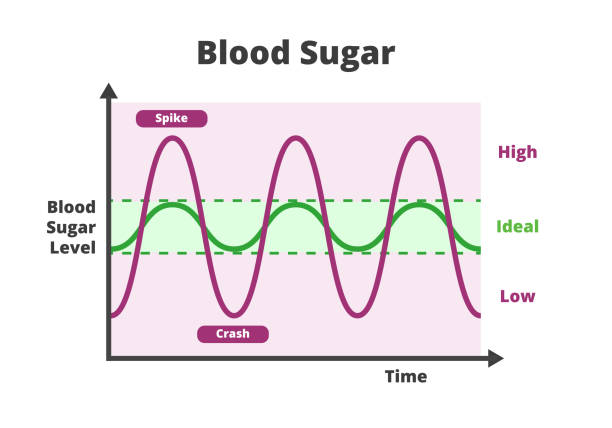

Glucose is carefully regulated by the body, maintaining levels within a narrow range. Too much, and you risk damage to organs and vessels, a hallmark of diabetes. Too little, and you face hypoglycemia, a sudden depletion of energy that can make you dizzy, confused, or even unconscious. While high blood sugar gets much of the spotlight in public discourse, low blood sugar—or hypoglycemia—can be just as dangerous and far more sudden.

Hypoglycemia isn’t a disease in itself; it is a symptom of an underlying problem. To understand what causes hypoglycemia, we must first grasp how the body regulates blood sugar, what happens when those systems fail, and what types of circumstances or conditions can push glucose below safe thresholds.

The Role of Insulin and Counter-Regulatory Hormones

Imagine the body as a finely tuned orchestra, where glucose regulation is a complex performance involving several hormones, with insulin playing lead violin. Produced by the pancreas, insulin helps transport glucose from the bloodstream into muscle, fat, and liver cells. It ensures that blood sugar doesn’t stay elevated after meals.

But insulin doesn’t work alone. Its counterparts—called counter-regulatory hormones—are tasked with doing the opposite. These include glucagon, epinephrine (adrenaline), cortisol, and growth hormone. They raise blood sugar levels when they fall too low. For example, glucagon stimulates the liver to release stored glucose, while adrenaline spurs the breakdown of glycogen and fat for energy during stress.

Together, insulin and its counter-regulators form a delicate push-pull system. When blood sugar begins to dip, insulin secretion slows and counter-regulatory hormones increase. However, this balance can be disrupted by medications, diseases, tumors, lifestyle factors, and even hormonal deficiencies, each potentially causing hypoglycemia through different mechanisms.

The Most Common Culprit Medication-Induced Hypoglycemia

By far the most frequent cause of hypoglycemia—especially in adults—is medication. Specifically, drugs used to treat diabetes, such as insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents, can tip the scales too far. In people with diabetes, insulin may be injected to control high blood sugar. But dosing errors, skipping meals, or unexpected exercise can cause too much glucose to be absorbed from the blood, leading to hypoglycemia.

Sulfonylureas and meglitinides are classes of diabetes medications that stimulate the pancreas to produce insulin. If someone takes these drugs but doesn’t eat enough, they might end up with excess insulin and dangerously low blood sugar. Long-acting sulfonylureas can be particularly tricky, causing prolonged hypoglycemia that may last for hours or even days.

Alcohol can exacerbate this. Drinking heavily on an empty stomach can suppress the liver’s ability to release glucose, especially when combined with glucose-lowering medications. In emergency rooms, one of the most common scenarios involves diabetic patients who drank alcohol and forgot to eat, resulting in severe hypoglycemia that needs urgent care.

Reactive Hypoglycemia and the Paradox of a Normal Pancreas

Not all hypoglycemia is caused by diabetes medication. Some people experience low blood sugar despite having no underlying disease. A classic example is reactive hypoglycemia, which typically occurs a few hours after eating, particularly following a high-carbohydrate meal.

In reactive hypoglycemia, the body overshoots its insulin response. Imagine having a big slice of cake, sending your blood sugar soaring. In response, the pancreas releases a flood of insulin. But in some individuals, the insulin surge is too aggressive, dragging glucose down to abnormally low levels a couple of hours later. The result can be symptoms like shakiness, sweating, irritability, and intense hunger.

This type of hypoglycemia is often seen in people who are insulin-sensitive or those who’ve undergone certain types of stomach surgery, such as gastric bypass. In such cases, food moves too quickly from the stomach into the small intestine, creating a rapid spike and then a crash in blood sugar.

Reactive hypoglycemia is generally mild and can be managed with dietary adjustments—smaller, more frequent meals that are lower in refined carbohydrates and richer in protein and fiber.

Fasting and Malnutrition A Battle Between Supply and Demand

Sometimes, hypoglycemia is a matter of insufficient supply. Prolonged fasting, starvation, or extreme calorie restriction can deplete the body’s glucose reserves. Normally, the liver acts as a warehouse, storing glycogen that it can break down into glucose when food isn’t available. But after 12 to 24 hours without eating, those stores run dry.

This is where gluconeogenesis comes in—a metabolic pathway in the liver and kidneys that creates new glucose from amino acids and fats. However, this system isn’t perfect and takes time to ramp up. In people who are already malnourished or have liver dysfunction, the body may not be able to maintain adequate glucose production.

Children are especially vulnerable to fasting-induced hypoglycemia. Their smaller glycogen reserves and higher metabolic rate mean they burn through energy stores quickly. That’s why even short periods without food can cause hypoglycemia in infants and young children, particularly if they’re ill.

In adults, fasting hypoglycemia is often seen in eating disorders, chronic alcohol abuse, or during extended fasts undertaken for religious or health reasons without proper preparation. It is also a concern in people who have undergone bariatric surgery, where nutritional absorption is compromised.

Hormonal Disorders That Sabotage Glucose Control

A lesser-known but important set of causes involves hormonal imbalances. Because glucose regulation is tightly controlled by hormones, any disruption in this system can result in hypoglycemia. Two key conditions illustrate this well: adrenal insufficiency and hypopituitarism.

In adrenal insufficiency—whether due to Addison’s disease or damage to the adrenal glands—the body fails to produce enough cortisol, a hormone essential for maintaining blood sugar, especially during stress or fasting. Without adequate cortisol, the liver struggles to generate new glucose, and tissues become more sensitive to insulin.

Similarly, the pituitary gland in the brain plays a central role in orchestrating hormone release. If it becomes damaged, either from tumors, trauma, or congenital disorders, the resulting hormonal deficiency can blunt the body’s ability to raise blood sugar. Hypopituitarism reduces levels of ACTH (which stimulates cortisol) and growth hormone—both of which are crucial counter-regulators.

People with these disorders may experience hypoglycemia during illness, stress, or fasting—times when the body would normally rally its hormonal defenses to maintain glucose balance.

The Enigmatic Insulinoma and Other Tumors

Occasionally, the cause of hypoglycemia is a tumor—a small, insulin-secreting growth in the pancreas known as an insulinoma. These rare but dramatic tumors arise from beta cells and pump out insulin regardless of the body’s actual needs. The result is persistent or recurring hypoglycemia, often with symptoms occurring in the early morning or after exercise.

Insulinomas can be difficult to diagnose because symptoms mimic those of anxiety or other neurological issues. A person might feel jittery, lightheaded, or mentally foggy, and not realize that their brain is starving for glucose. Over time, these episodes can become more severe, leading to confusion, seizures, or loss of consciousness.

Diagnosis usually involves a supervised fast in a hospital setting, during which glucose, insulin, and C-peptide levels are measured. If insulin levels remain high even when glucose is dangerously low, it suggests an insulin-producing tumor. Imaging studies like CT, MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound can then locate the tumor, which is typically cured by surgical removal.

Other tumors can also cause hypoglycemia, though indirectly. Large tumors (especially in the liver or adrenal glands) can consume massive amounts of glucose or secrete substances that mimic insulin. These are rare, but when they occur, they tend to be part of a larger and more ominous clinical picture.

Inborn Errors of Metabolism When Genetics Sabotage Energy

In infants and children, inherited metabolic disorders are an important and sometimes overlooked cause of hypoglycemia. These are genetic defects that impair the body’s ability to metabolize sugars, fats, or amino acids. Common examples include glycogen storage diseases, fatty acid oxidation disorders, and galactosemia.

Children with these conditions may appear normal at birth but soon develop symptoms such as lethargy, vomiting, seizures, or failure to thrive. Hypoglycemia in these cases is not simply a lack of food—it’s a breakdown in the cellular machinery needed to extract energy from it.

These disorders often require specialized testing and management. Treatments may include strict dietary control, avoidance of fasting, and in some cases, enzyme replacement or liver transplantation. Early diagnosis through newborn screening can dramatically improve outcomes, but in undiagnosed cases, hypoglycemia may be the first and most dangerous clue.

The Nervous System’s Warning Signs and Desperate Measures

When blood sugar drops, the brain—which relies almost exclusively on glucose—starts to suffer first. This is why the symptoms of hypoglycemia often begin with what doctors call “adrenergic” effects: shakiness, sweating, palpitations, anxiety. These are driven by the sympathetic nervous system and serve as an alarm to get you to eat.

If glucose continues to fall, the symptoms become neuroglycopenic—meaning the brain isn’t getting enough sugar. This leads to confusion, blurred vision, difficulty speaking, seizures, and eventually coma. These effects are more dangerous and can occur without much warning in people with frequent hypoglycemia who have lost their early warning symptoms—a condition called hypoglycemia unawareness.

The body can adapt to low blood sugar over time, but this adaptation can be a double-edged sword. While it may reduce symptoms temporarily, it also raises the risk of severe, unnoticed hypoglycemia. This is especially dangerous during sleep or in those who live alone, as the ability to self-correct through food intake is impaired.

How Lifestyle and Exercise Play a Role

Even healthy individuals can experience hypoglycemia under certain circumstances. Athletes who engage in prolonged or intense exercise without adequate nutrition may deplete their glycogen stores, especially if they’re training fasted. This type of exercise-induced hypoglycemia can cause fatigue, poor performance, and lightheadedness during or after activity.

In people with diabetes, physical activity can magnify the effects of insulin, lowering blood sugar both during and after exercise. Managing this requires careful planning—adjusting insulin doses, monitoring glucose levels, and consuming carbohydrates before, during, or after workouts.

Stress, sleep deprivation, and erratic eating patterns can also affect glucose regulation. While they may not cause hypoglycemia outright, they can lower the threshold at which symptoms occur or exacerbate an underlying condition.

When the Diagnosis Isn’t Obvious

Identifying the cause of hypoglycemia can be challenging. It requires a combination of careful history-taking, laboratory testing, and sometimes hospital observation. Important clues include the timing of symptoms, recent medications, dietary habits, and underlying medical conditions.

Doctors often use Whipple’s triad to establish a true diagnosis of hypoglycemia: (1) low plasma glucose, (2) symptoms of hypoglycemia, and (3) relief of symptoms after glucose intake. This helps differentiate genuine hypoglycemia from conditions that may mimic it, such as anxiety, dehydration, or certain neurologic disorders.

Once a cause is found, treatment can be tailored accordingly—whether it’s adjusting a medication, removing a tumor, correcting a hormone deficiency, or managing a chronic illness. For many, lifestyle changes and education are enough to keep hypoglycemia from returning.

The Lifesaving Power of Awareness

Hypoglycemia may seem like a fleeting inconvenience, but for those affected, it can be life-altering—or even life-threatening. Its causes range from everyday situations to rare medical conditions, but the unifying thread is a mismatch between the body’s energy needs and its available supply.

Fortunately, most cases can be prevented or managed with knowledge, vigilance, and medical guidance. Whether you live with diabetes, a hormonal disorder, or no diagnosis at all, understanding the signals your body sends—and responding to them with care—can prevent the spiraling effects of low blood sugar.

In the grand symphony of physiology, glucose is the note that must never falter. When it does, the consequences ripple across every system. But with the right knowledge, hypoglycemia need not be a mystery or a menace. It becomes, instead, a condition that can be understood, anticipated, and ultimately controlled.