Vitiligo is not just a skin condition—it is a story written in contrasting shades across the human body. For those who live with it, vitiligo can become a canvas of visible difference, often drawing unwanted attention and misunderstandings. Scientifically, vitiligo is an acquired disorder in which the pigment-producing cells of the skin, called melanocytes, are destroyed or stop functioning, leading to white patches of varying size and shape.

But vitiligo is more than biology. It affects how people see themselves, how society responds to visible differences, and how individuals find strength in their uniqueness. To truly understand vitiligo, we must explore its medical science, its emotional and social impact, and the treatments that can help manage it.

What Is Vitiligo?

Vitiligo is a chronic skin condition characterized by the progressive loss of pigmentation in certain areas of the skin. Melanin, the pigment responsible for giving skin, hair, and eyes their color, is produced by melanocytes. When these cells are destroyed or stop functioning, melanin production halts, leaving behind white or light-colored patches.

Vitiligo is not contagious and does not directly threaten physical health. However, because skin is the body’s most visible organ, the condition carries a profound psychosocial impact. People living with vitiligo may struggle with self-esteem, anxiety, or depression, not because of the disease itself, but because of stigma and misunderstanding.

Globally, vitiligo affects about 0.5% to 2% of the population, touching millions of lives across all ethnicities, genders, and ages. It can appear at any stage of life, though many cases begin before the age of 20.

The Science of Pigmentation: Why Color Matters

To understand vitiligo, one must first understand pigmentation. Melanocytes reside in the basal layer of the epidermis, producing melanin through a process called melanogenesis. Melanin not only gives skin its color but also protects it from harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

There are two primary forms of melanin:

- Eumelanin, which is brown to black,

- Pheomelanin, which is yellow to red.

The balance and distribution of these pigments determine skin tone. In vitiligo, melanocytes vanish or become dysfunctional, creating patches of unpigmented skin that stand in contrast with normally pigmented areas.

This loss of pigment is not merely cosmetic—it disrupts the skin’s protective role, making depigmented areas more vulnerable to sun damage.

Causes of Vitiligo: Why Does It Happen?

Vitiligo’s exact cause remains complex, and no single explanation can fully account for all cases. Instead, scientists believe it results from a combination of genetic, autoimmune, environmental, and oxidative stress factors.

Autoimmune Hypothesis

The most widely accepted theory is that vitiligo is an autoimmune disorder. In this model, the immune system mistakenly identifies melanocytes as harmful and attacks them, leading to their destruction. Elevated levels of autoantibodies and autoreactive T-cells in people with vitiligo support this theory.

Genetic Factors

Vitiligo often runs in families, suggesting a genetic predisposition. More than 30 genetic loci have been associated with increased susceptibility, many of which are linked to immune system regulation. However, inheritance is not straightforward; not everyone with a family history develops the condition.

Oxidative Stress

Another explanation involves oxidative stress, where an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants damages melanocytes. Excess hydrogen peroxide accumulation in the skin has been observed in vitiligo patients, potentially contributing to melanocyte death.

Environmental Triggers

Environmental factors may also play a role in triggering vitiligo in genetically susceptible individuals. These include:

- Severe sunburn,

- Chemical exposure (e.g., phenolic compounds),

- Physical trauma to the skin (a phenomenon known as the Koebner effect),

- Emotional stress.

Neural Hypothesis

Some researchers suggest that dysfunction in the nerve supply to the skin might influence melanocyte survival. This may explain cases where vitiligo follows dermatomal or segmental patterns.

In reality, vitiligo likely arises from an interplay of these mechanisms, with each individual case shaped by unique biological and environmental factors.

Symptoms of Vitiligo

Vitiligo is primarily recognized by the appearance of white or depigmented patches on the skin. These patches can develop anywhere, but common sites include:

- Hands and feet,

- Face (especially around the eyes and mouth),

- Armpits and groin,

- Elbows and knees,

- Scalp and hair, leading to premature graying.

Types of Vitiligo

- Generalized Vitiligo: The most common form, with widespread symmetrical patches.

- Segmental Vitiligo: Limited to one side or a specific area, often stable after initial spread.

- Focal Vitiligo: A few isolated patches in a localized region.

- Universal Vitiligo: Rare, with depigmentation affecting most of the body.

Progression

Vitiligo’s progression varies widely. In some individuals, patches remain localized and stable for years, while in others, depigmentation spreads rapidly. The unpredictability of its course is one of the most challenging aspects for patients.

Associated Symptoms

Vitiligo itself does not cause physical pain, itching, or other direct symptoms. However, it can be associated with other autoimmune disorders, such as:

- Thyroid disease (e.g., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis),

- Type 1 diabetes,

- Pernicious anemia,

- Alopecia areata.

Thus, vitiligo may sometimes serve as a visible marker of underlying immune dysfunction.

Diagnosis of Vitiligo

Diagnosis usually begins with a clinical evaluation by a dermatologist. The distinctive appearance of white patches is often enough to confirm suspicion, but additional tools and tests may be used to rule out other conditions.

Physical Examination

Dermatologists examine the distribution, symmetry, and extent of depigmented patches.

Wood’s Lamp Examination

A Wood’s lamp (UV light) highlights depigmented patches more clearly, helping distinguish vitiligo from other causes of hypopigmentation, such as tinea versicolor or pityriasis alba.

Medical History

Doctors may ask about family history, autoimmune disorders, recent stress, chemical exposures, or skin injuries to better understand potential triggers.

Laboratory Tests

Blood tests may be conducted to screen for associated autoimmune conditions, particularly thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 levels, and blood sugar checks.

Skin Biopsy

In rare cases, a biopsy may be performed. Under the microscope, skin samples from vitiligo show an absence of melanocytes.

Treatment of Vitiligo

Vitiligo has no universal cure, but a variety of treatments aim to restore skin color, halt disease progression, and improve quality of life. The best approach often depends on the extent, location, and activity of the condition, as well as individual preferences.

Topical Treatments

- Corticosteroid Creams: These can reduce inflammation and may restore pigment, particularly in early stages.

- Calcineurin Inhibitors (Tacrolimus, Pimecrolimus): Useful for sensitive areas like the face and neck, with fewer side effects than steroids.

Phototherapy

Light-based treatments stimulate melanocyte activity and repigmentation.

- Narrowband UVB Therapy: The most widely used and effective, especially for widespread vitiligo.

- Excimer Laser: Targets localized patches with high-intensity UVB.

Systemic Treatments

For rapidly spreading vitiligo, systemic immunosuppressants such as corticosteroids or methotrexate may be prescribed, though these carry significant side effects.

Surgical Options

In cases where vitiligo is stable (not spreading), surgical procedures may restore pigmentation:

- Skin Grafting: Transplanting healthy pigmented skin to depigmented areas.

- Melanocyte Transplantation: Culturing and transferring melanocytes to affected skin.

Depigmentation Therapy

For extensive vitiligo where repigmentation is not feasible, depigmentation of remaining pigmented skin can create a uniform appearance. Monobenzone cream is sometimes used for this purpose.

Emerging Treatments

Research into new therapies is rapidly advancing. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, for example, have shown promise in clinical trials for reversing depigmentation. Antioxidant therapies and stem-cell-based approaches are also under investigation.

Supportive Measures

- Sunscreen: Essential to protect depigmented areas from sunburn and prevent contrast with pigmented skin.

- Cosmetic Camouflage: Makeup and self-tanning products can help mask patches.

- Psychological Support: Counseling, support groups, and therapy play a vital role in managing the emotional impact of vitiligo.

Living with Vitiligo: The Human Experience

Vitiligo is as much an emotional journey as it is a medical condition. In many cultures, visible skin differences can lead to stigma, discrimination, or isolation. Children with vitiligo may face bullying, while adults may struggle with self-image and confidence.

Yet, there is also a growing movement toward embracing vitiligo as a part of identity. Public figures and models with vitiligo have helped challenge beauty standards, showing the world that uniqueness can be powerful. Campaigns and communities now celebrate vitiligo as a form of diversity rather than a flaw.

For many, managing vitiligo involves finding balance—between treatment and acceptance, between concealing and embracing. Mental health support and societal education are just as critical as medical interventions.

Vitiligo and Associated Conditions

Vitiligo often coexists with other autoimmune disorders. This does not mean everyone with vitiligo will develop another condition, but vigilance is important. Commonly associated disorders include:

- Autoimmune thyroid disease,

- Addison’s disease,

- Type 1 diabetes,

- Rheumatoid arthritis,

- Psoriasis.

This connection underscores the systemic nature of autoimmune activity and the need for holistic care.

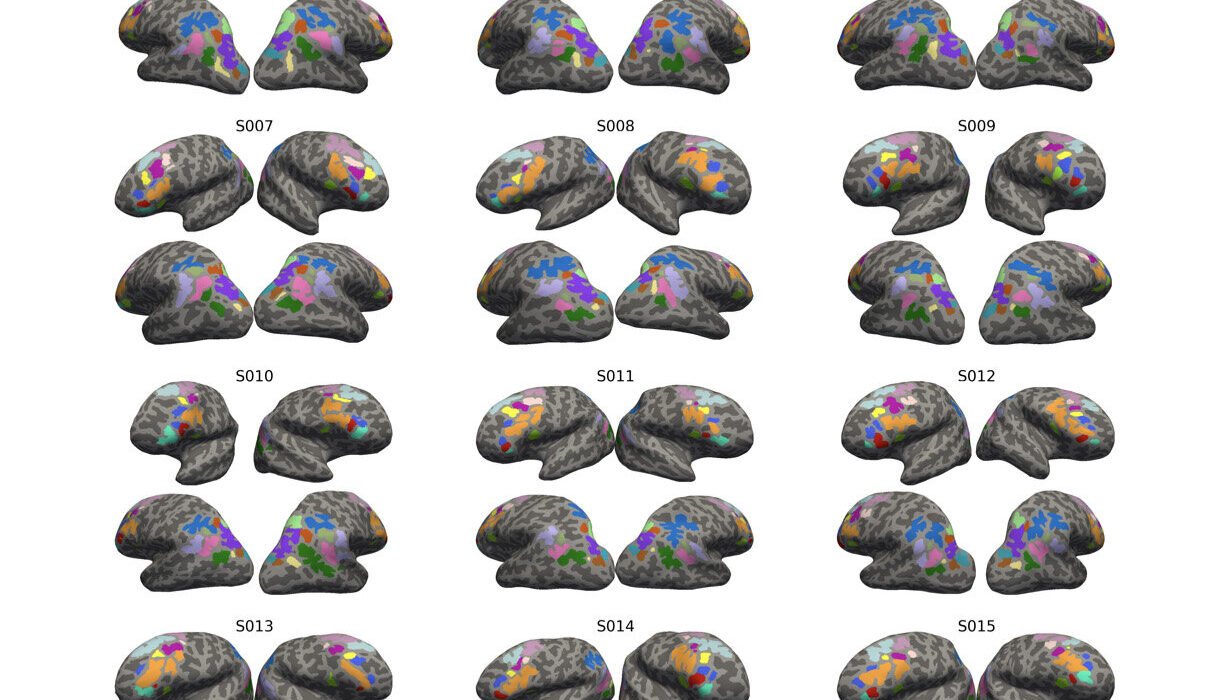

Future Directions in Vitiligo Research

The scientific community continues to explore vitiligo’s mysteries. Some promising areas include:

- Targeted Immunotherapies: Drugs that fine-tune immune responses to protect melanocytes without broad suppression.

- Cellular Regeneration: Harnessing stem cells to regenerate melanocytes.

- Genetic Insights: Understanding gene-environment interactions to predict risk and personalize treatment.

- Holistic Care Models: Integrating dermatology, psychology, and social support for comprehensive care.

These advances hold the promise of not only managing vitiligo but potentially preventing or reversing it in the future.

Conclusion: Redefining Beauty and Health

Vitiligo is more than a skin condition—it is a window into the complex interplay of genetics, immunity, and environment. While its patches may be visible, the true story of vitiligo lies in resilience, courage, and the redefinition of beauty.

For those living with vitiligo, treatment can help restore pigmentation and confidence, but acceptance and empowerment are equally vital. The condition challenges us as a society to look beyond appearances, to recognize health as not just the uniformity of skin but the vitality of the whole person.

Vitiligo does not diminish life—it adds to the spectrum of human diversity. And in that diversity, there is strength, beauty, and the shared humanity that connects us all.