Reproduction is one of the most fundamental biological processes in the natural world. It’s the process by which life continues, the bridge between generations, and the biological imperative that connects all living things. In humans, this process involves the intricate interplay of male and female reproductive systems—each a masterwork of evolutionary design. While the female system often takes center stage in conversations about childbirth and pregnancy, the male reproductive system is equally essential, responsible for the production, nourishment, and delivery of the crucial half of the genetic blueprint: sperm.

The male reproductive system is not just about creating sperm, however. It’s about generating the right conditions for fertility, sustaining hormone balance, and maintaining sexual health throughout a man’s life. In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll dive deep into the fascinating world of male reproductive anatomy and physiology—from the origins of sperm to the mechanisms of ejaculation and the hormones that orchestrate it all. We’ll also examine how this system develops, how it changes with age, and what can go wrong when it malfunctions.

The Big Picture: Purpose and Function of the Male Reproductive System

At its core, the male reproductive system has three primary responsibilities: to produce sperm (the male gametes), to synthesize and regulate the hormone testosterone (crucial for development and sexual function), and to deliver sperm to the female reproductive tract during intercourse. These tasks may sound simple on the surface, but they require a remarkably complex network of organs, ducts, and glands all working together in perfect harmony.

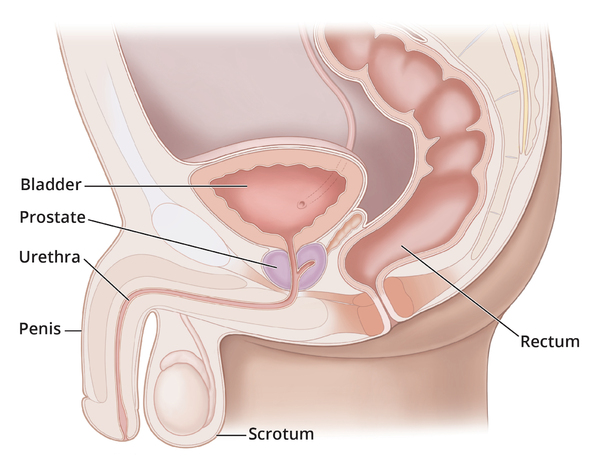

This system is split between external organs, which are visible outside the body and involved in sexual interaction, and internal organs, which are responsible for sperm production, storage, and transport. Let’s begin by examining these structures in detail.

External Anatomy: The Visible Elements of Fertility

The Penis: A Multifunctional Marvel

The penis is the most visible component of the male reproductive system, and it serves multiple purposes. It acts as a conduit for both urine and semen and plays a key role in sexual arousal and reproduction.

Structurally, the penis contains three columns of erectile tissue: two corpora cavernosa and one corpus spongiosum. During arousal, these tissues fill with blood, causing the penis to become erect—an essential prerequisite for intercourse and sperm delivery. The tip of the penis, known as the glans, is highly sensitive and plays a significant role in sexual pleasure. Covering the glans is the foreskin (or prepuce), which may be removed in circumcision.

Running through the penis is the urethra, a shared channel for both urine and semen—though never at the same time, thanks to a muscular valve that ensures reproductive and urinary functions remain distinct.

The Scrotum: Nature’s Thermal Cradle

Beneath the penis lies the scrotum, a loose pouch of skin and muscle that houses the testes, or testicles. It might look like a simple sac, but the scrotum performs an elegant and essential function: thermoregulation. Sperm production occurs optimally at temperatures slightly lower than core body temperature. The scrotum responds to changes in ambient temperature by contracting or relaxing, moving the testes closer to or farther from the body.

Tiny muscles called the dartos and cremaster regulate this movement with incredible precision. When it’s cold, the scrotum contracts and wrinkles, pulling the testes closer to preserve heat. In warmer conditions, it relaxes, allowing the testes to cool. This dynamic thermostat plays a key role in male fertility.

Internal Anatomy: The Hidden Machinery of Reproduction

The Testes: The Sperm and Hormone Factories

The testes are the paired oval-shaped organs within the scrotum. Each is about the size of a walnut, but their role in male biology is colossal. They are the primary reproductive organs responsible for two essential functions: producing sperm and synthesizing testosterone.

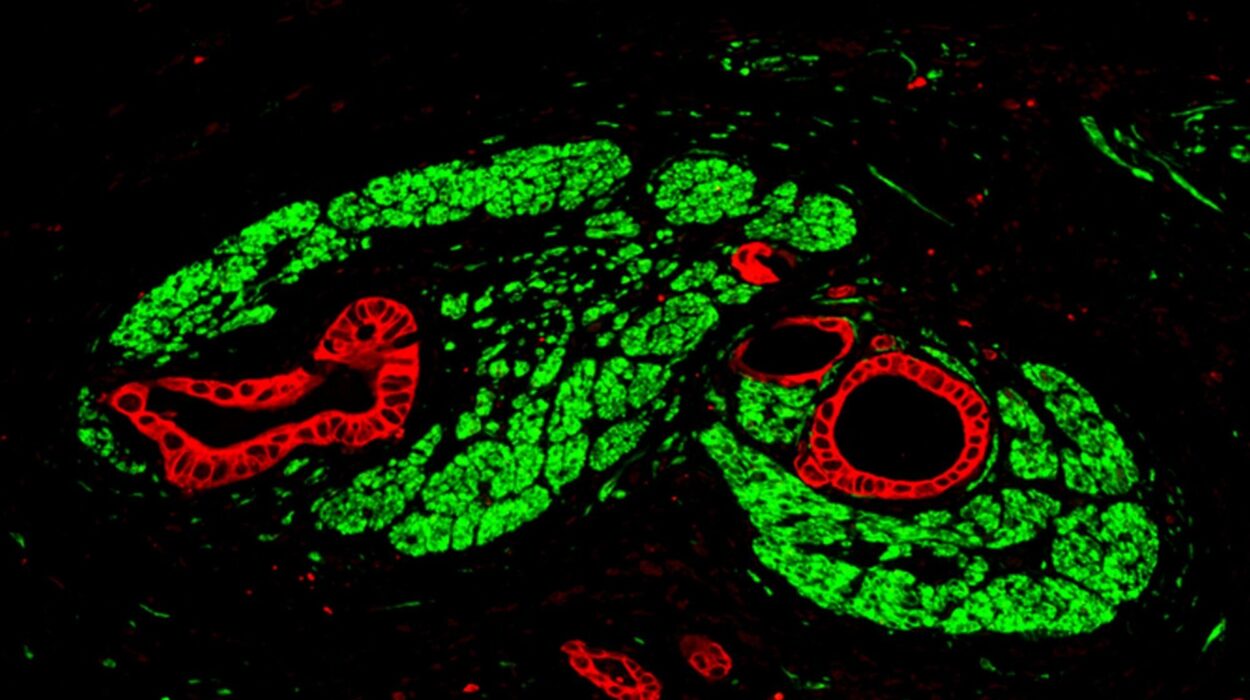

Inside each testis are seminiferous tubules, tightly coiled structures where spermatogenesis (sperm production) takes place. These tubules are lined with specialized cells that nurture developing sperm cells and facilitate their transformation from primitive germ cells to motile, mature spermatozoa.

Between the tubules are Leydig cells, which produce testosterone. This powerful hormone drives male sexual development, supports libido, maintains muscle mass and bone density, and regulates the production of sperm itself.

Sperm production begins at puberty and continues throughout a man’s life—though it tends to decline gradually with age. A healthy man can produce millions of sperm per day, a testament to the reproductive system’s staggering productivity.

The Epididymis: A Finishing School for Sperm

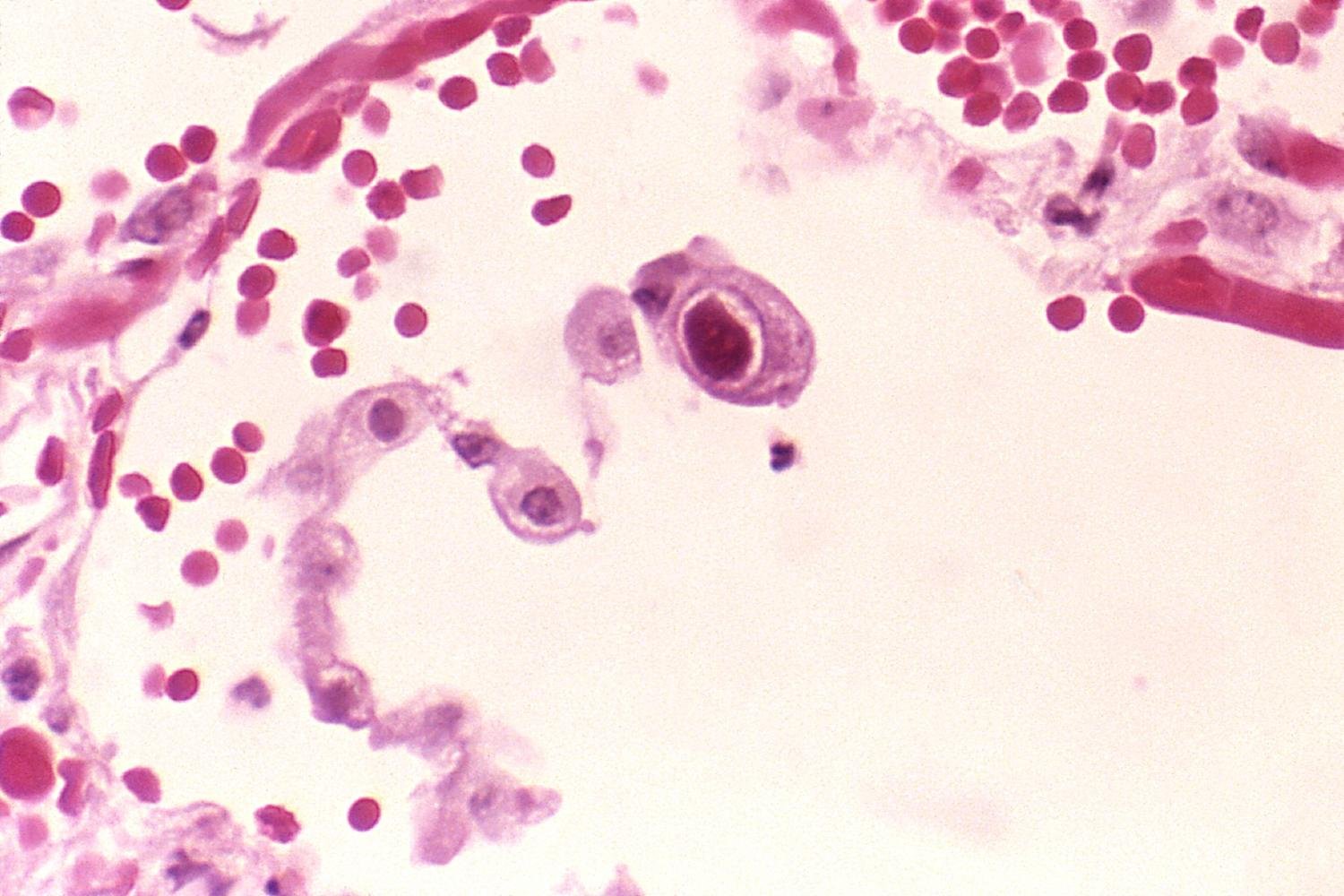

After being created in the seminiferous tubules, immature sperm move into the epididymis, a long, coiled tube that rests atop each testis. The epididymis is not just a storage depot—it’s a refinement center. Over several days, sperm undergo biochemical changes here that enable them to swim and fertilize an egg. Without this crucial maturation process, sperm would remain functionally inert.

The epididymis also stores sperm until ejaculation. When ejaculation occurs, muscular contractions push the sperm into the next structure: the vas deferens.

The Vas Deferens: The Sperm Highway

The vas deferens is a thick-walled muscular tube that transports sperm from the epididymis to the ejaculatory ducts, located behind the bladder. During ejaculation, peristaltic contractions in the vas deferens propel sperm forward with surprising speed. This tube is also the site targeted during a vasectomy, a surgical procedure for male sterilization in which the vas deferens is cut and sealed, preventing sperm from reaching the ejaculate.

Seminal Vesicles and Prostate Gland: Makers of Semen

Sperm alone make up only about 5% of semen volume. The rest is fluid produced by accessory glands, which nourish, protect, and help transport sperm.

The seminal vesicles contribute about 60% of semen content. Their secretion is rich in fructose, providing sperm with the energy needed for their long journey toward the egg. The fluid is also alkaline, helping to neutralize the acidic environment of the female reproductive tract.

The prostate gland, about the size of a walnut, surrounds the urethra just below the bladder. It contributes enzymes and a slightly milky fluid to semen that enhances sperm motility and longevity. One important enzyme is prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which helps liquefy semen after ejaculation, allowing sperm to swim more freely.

Finally, the bulbourethral glands, or Cowper’s glands, secrete a small amount of lubricating fluid during sexual arousal. This pre-ejaculate fluid neutralizes any acidity in the urethra from leftover urine, preparing a safer path for sperm.

The Hormonal Orchestra: Endocrine Control of Reproduction

Behind the scenes of sperm production and sexual function is a symphony of hormonal signals orchestrated by the brain. This hormonal axis begins in the hypothalamus, a part of the brain that releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in rhythmic pulses. GnRH stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to release two critical hormones: luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

LH travels to the testes and stimulates Leydig cells to produce testosterone. FSH, meanwhile, works in concert with testosterone to activate the Sertoli cells inside seminiferous tubules, promoting sperm development.

Testosterone itself provides negative feedback to the brain and pituitary, keeping the system in balance. Too much or too little testosterone can disrupt this delicate dance, leading to infertility, reduced libido, or developmental disorders.

Ejaculation and Orgasm: The Grand Finale

Ejaculation is the coordinated climax of male sexual activity. It involves two phases: emission and expulsion. During emission, sperm travel from the epididymis through the vas deferens and mix with seminal fluid to form semen. During expulsion, strong rhythmic contractions of the pelvic floor muscles propel the semen out through the urethra.

This process is tightly controlled by the autonomic nervous system, with the sympathetic nervous system triggering ejaculation and the parasympathetic system responsible for erection. Orgasm is the subjective pleasurable sensation that accompanies ejaculation, though the two events can, in rare cases, be separated.

Developmental Biology: From Boyhood to Manhood

The male reproductive system does not function from birth. Instead, it undergoes dramatic changes during puberty, triggered by a surge in testosterone production. The testes enlarge, pubic and facial hair appears, the voice deepens, and the penis grows. These secondary sexual characteristics, along with the onset of spermatogenesis, mark the beginning of reproductive capability.

During embryonic development, the presence of the SRY gene on the Y chromosome prompts the formation of male structures. In its absence, the default pathway is female. Hormones like anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and testosterone direct the differentiation of male internal and external genitalia in the fetus.

Aging and the Male Reproductive System

While men remain fertile much longer than women, the male reproductive system does age. After age 40, testosterone levels begin to decline gradually in a process sometimes referred to as andropause. This can lead to reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, decreased muscle mass, and sometimes mood changes.

Sperm production also decreases with age, and DNA damage in sperm may increase, potentially affecting fertility and offspring health. Nevertheless, many men remain fertile well into their later decades, and some father children in their 60s or even beyond.

Disorders and Diseases: When Systems Go Wrong

Like any complex system, the male reproductive system is susceptible to disorders. Erectile dysfunction (ED) affects millions of men and can result from vascular, neurological, hormonal, or psychological causes. Treatments range from lifestyle changes and medications like sildenafil (Viagra) to mechanical aids or surgery.

Prostate issues, including benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer, become more common with age. BPH causes urinary difficulties due to prostate enlargement, while prostate cancer is a leading cancer among men, often detected by elevated PSA levels or digital rectal exams.

Infertility affects around 10–15% of couples, and in about half of cases, male factors are involved. These may include low sperm count, poor motility, structural abnormalities, or genetic disorders.

Testicular cancer, though rare, is the most common cancer in young men aged 15–35. It’s highly treatable, especially when detected early, highlighting the importance of regular self-exams.

Conclusion: A System of Power, Precision, and Potential

The male reproductive system is a masterpiece of biological engineering—both robust and finely tuned. It is responsible for creating and delivering the genetic essence of life, sustained by a powerful hormonal framework and a coordinated network of organs and glands.

From the silent production of sperm deep within the testes to the drama of ejaculation and orgasm, from the hormonal cascades of puberty to the challenges of aging, the male reproductive system plays a vital role in health, identity, and the continuation of the human species.

To understand it is not just to learn anatomy—it is to witness a marvel of evolution, complexity, and life itself.