For decades, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) have felt like cruel riddles. They arrive quietly, then reshape lives with relentless force. In FTD, the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes begin to falter, altering personality, behavior, and language in ways that can feel like watching a loved one slowly slip away. In ALS, motor neurons—the cells that allow us to move—gradually die, leading to muscle weakness and paralysis.

Doctors and scientists have searched for answers in genes, in environmental exposures, in injuries, even in diet. Yet in many cases, the true cause has remained painfully out of reach. Why do some people develop these devastating neurodegenerative diseases while others, even those with similar genetic risks, do not?

Now, researchers at Case Western Reserve University believe they have uncovered a missing piece of the puzzle. And astonishingly, it begins not in the brain—but in the gut.

A Sugar with a Dark Side

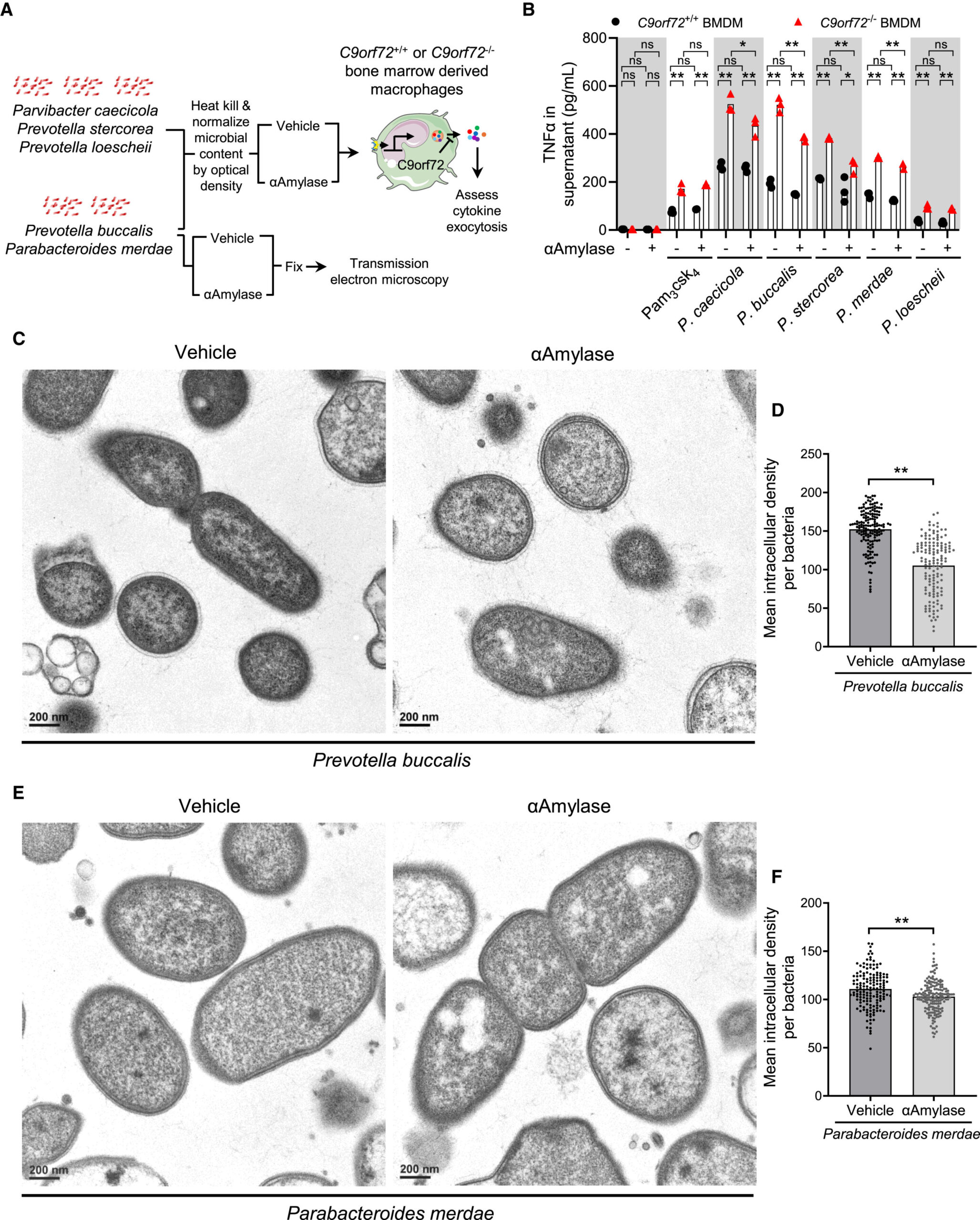

The discovery, recently published in Cell Reports, centers on something deceptively simple: glycogen, a type of sugar. But this is not the glycogen we typically think of as stored energy in our own cells. Instead, the focus is on inflammatory forms of glycogen produced by certain gut bacteria.

According to Aaron Burberry, assistant professor in the Department of Pathology at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine and senior investigator of the study, harmful gut bacteria can generate these inflammatory glycogen molecules. Once produced, these sugars trigger immune responses. And those immune responses, meant to protect the body, can instead damage brain cells.

The idea is both elegant and unsettling. A molecular signal originating in the digestive system can ripple outward, activating immune pathways that ultimately contribute to the deterioration of the brain.

The team examined 23 ALS/FTD patients, and the results were striking. About 70% of them had high levels of these dangerous glycogen forms. Among individuals without the brain diseases, only about a third showed similarly elevated levels.

This pattern suggests more than coincidence. It points to a biological bridge—one that connects gut microbes, immune activation, and neurodegeneration.

The Genetic Puzzle Finally Makes Sense

For years, scientists have been especially puzzled by carriers of the C90RF72 mutation, the most common genetic cause of ALS and FTD. Not everyone with this mutation develops disease. Some do. Some don’t. The question has lingered like a shadow: what tips the balance?

This study offers an explanation. It identifies gut bacteria as a key environmental trigger that may determine whether a genetically at-risk individual actually develops the disease.

In other words, genes may load the gun—but the gut may pull the trigger.

By revealing this molecular link, the research helps explain why some people with the mutation become ill while others remain unaffected. It shifts the narrative from pure genetics to a more complex interplay between genes and the environment—specifically, the microscopic ecosystem inside our digestive tract.

Inside the Sterile World That Made It Possible

Discoveries like this don’t happen by accident. They require unusual tools and environments. At Case Western Reserve, researchers have access to something rare: germ-free mouse models. These mice are raised in completely sterile conditions, without any bacteria.

Why does that matter? Because it allows scientists to introduce specific gut microbes and observe precisely how they affect the brain. Without the noise of other microorganisms, cause and effect become clearer.

The program is led by Fabio Cominelli, Distinguished University Professor and director of the Digestive Health Research Institute. A critical innovation behind the work is a specialized “cage-in-cage” sterile housing system developed by Alex Rodriguez-Palacios, assistant professor in the Digestive Health Research Institute.

This setup allows researchers to conduct large-scale microbiological studies that would be impossible using traditional methods, which typically accommodate only a handful of mice at a time. The sterile system makes it possible to systematically explore how particular gut bacteria produce harmful glycogen and how those sugars influence the brain.

In this carefully controlled world, the invisible conversations between gut microbes and neurons begin to reveal themselves.

Rewriting the Future of Treatment

Perhaps the most hopeful aspect of the study is what happened next. After identifying the harmful sugars, the team worked to reduce them. When they did, they saw something extraordinary: brain health improved and lifespan extended.

The implication is profound. If inflammatory glycogen from gut bacteria contributes to brain cell death, then breaking down or preventing the production of these sugars could become a new therapeutic strategy.

The findings immediately suggest new treatment targets for ALS and FTD. They also introduce potential biomarkers—measurable indicators that could help identify which patients might benefit from therapies aimed at the gut.

Rather than focusing solely on the brain, doctors might one day treat these neurodegenerative diseases by adjusting the microbial chemistry of the digestive system. The gut, once considered peripheral to neurological disease, may become central to intervention.

The research team is already looking ahead. They plan to conduct larger studies examining the gut microbiome communities of ALS and FTD patients before and after disease onset. Understanding when and why harmful microbial glycogen is produced will be crucial.

Clinical trials designed to test whether degrading glycogen in patients can slow disease progression could begin within a year, supported by these findings.

Why This Discovery Matters

For families facing ALS or FTD, time feels fragile. These diseases progress steadily, often without effective treatments that alter their course. A discovery that identifies not just a risk factor but a modifiable one changes the emotional landscape.

This research matters because it transforms an abstract mystery into a tangible pathway. It identifies a molecular connection linking gut bacteria, inflammatory sugars, immune responses, and brain cell death. It explains why certain genetic mutation carriers become sick while others do not. And it introduces practical targets for intervention.

Most importantly, it reframes how we think about neurodegenerative disease. The brain does not exist in isolation. It is in constant dialogue with the rest of the body, including the trillions of microbes living in the gut. When that dialogue goes wrong, the consequences can be devastating. But when we understand the language—down to the level of a single sugar molecule—we gain the power to intervene.

If future clinical trials confirm these findings, treatments for ALS and FTD may one day involve not just neurologists, but experts in digestive health. The fight against neurodegeneration could begin with restoring balance in the gut.

In a field long marked by unanswered questions, this discovery offers something rare: clarity. It suggests that by targeting harmful bacterial glycogen and calming the immune response it provokes, we may be able to slow or even alter the course of diseases that once seemed unstoppable.

And all of it began with a simple, startling realization—the gut was whispering to the brain all along.

Study Details

Blake McCourt et al, C9orf72 in myeloid cells prevents an inflammatory response to microbial glycogen, Cell Reports (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2025.116906