For centuries, the image has felt almost too dramatic to be real. Massive elephants lumbering across battlefields, armored and towering, carrying soldiers into war. Ancient writers described them. Artists carved them into stone and pressed them onto coins. Stories of Hannibal and his elephants echoed through classrooms, books, and films. Yet for all that imagery, something essential was missing. No bones. No physical trace of those legendary animals had ever been found in the places and time of the Punic Wars.

That silence lasted until 2020, when a single, battered bone emerged from rubble in southern Spain. It was small enough to hold in two hands, only about 10 centimeters across, cube-shaped and worn. But it carried the weight of centuries of doubt and imagination. Found at the Colina de los Quemados site in Córdoba, it may finally anchor the legend of war elephants to the ground of history.

The Wars That Shaped an Empire

The Punic Wars, fought between 264 and 146 BCE, were a brutal struggle between the Roman Republic and the Carthaginian Empire. Three wars, decades of violence, and a reshaping of the Mediterranean world. Among all the generals and battles, one name endures most vividly: Hannibal, the Carthaginian commander whose campaigns terrified Rome.

Hannibal’s elephants became symbols of both ingenuity and intimidation. Ancient accounts describe them as living war machines, unfamiliar and frightening to Roman troops. Over time, these descriptions hardened into legend. Coins showed riders atop elephants. Sculptures placed their massive forms in stone. Western culture absorbed the image and repeated it, generation after generation.

As the study’s authors note, the image of Hannibal leading elephants across Europe left “a profound mark on Western art, literature, and culture.” Musicians, writers, playwrights, and eventually filmmakers all returned to that same unforgettable scene. Yet archaeology lagged behind storytelling. The elephants remained visible only in words and images, not in the soil.

Evidence Without Bones

Before the Córdoba discovery, nearly all evidence for war elephants came from historical accounts, iconography, and artifacts. Coins showed a man riding an elephant. A sculpture from the Roman necropolis of Carmona depicted the animal’s unmistakable shape. These objects confirmed belief, but they did not prove presence in a biological sense.

There were hints elsewhere. At Col de la Traversette in the southern Alps, researchers reported chemical and organic markers that some historians associate with Hannibal’s famous crossing of the Alps in 218 BCE. According to historical estimates, that march involved more than 30,000 infantry, 7,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants. But markers are not bones, and debate continued.

Without skeletal remains, skeptics could still ask whether elephants truly reached these regions in wartime, or whether later retellings exaggerated their role. The story remained powerful, but incomplete.

A Construction Site and a Surprise

The discovery in Córdoba was not part of a hunt for elephants. Archaeologists were excavating the Colina de los Quemados site ahead of the expansion of the Córdoba Provincial Hospital. The hill had been occupied for thousands of years, with evidence of human presence stretching back to the mid-3rd millennium BCE. It appeared to have been abandoned around the time a Roman military camp was established, a camp that would later grow into the modern city.

As excavation progressed, the team uncovered a layer of destruction. Rubble, collapsed walls, and signs of violent disruption marked a single level of occupation. Beneath a fallen adobe wall, sealing that layer like a time capsule, lay the bone.

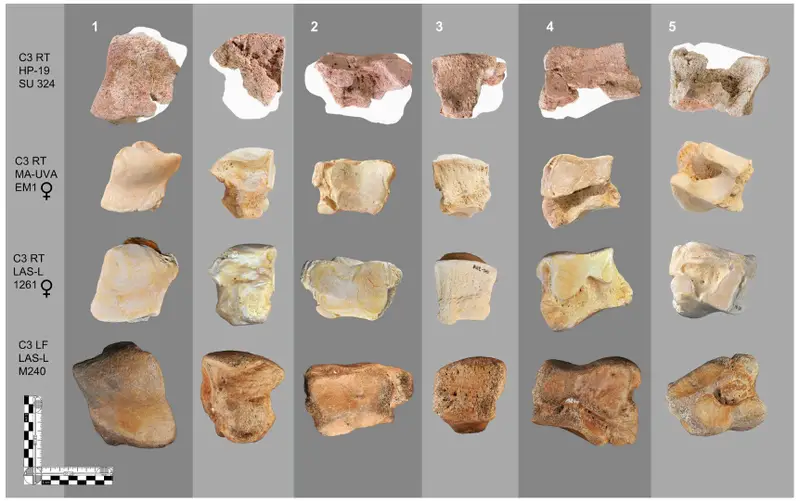

At first, its identity was uncertain. Time had not been kind to it. The bone was poorly preserved, cracked, and eroded. Yet its shape was distinctive. After careful comparison with modern elephant bones and fossilized mammoth specimens, the researchers identified it as a carpal bone from an elephant’s wrist.

In a site crowded with human history, this non-human fragment stood out sharply.

Reading Time from a Fragment

The bone could not reveal everything. Its condition ruled out DNA or protein analysis, meaning the researchers could not determine whether it came from an Asian or African elephant. But one crucial question remained answerable: when did this animal live?

Using radiocarbon dating on the bone’s mineral fraction, the team narrowed its age to between the late 4th and early 3rd centuries BCE. That range aligns closely with the period of the Second Punic War, the very conflict in which Hannibal’s elephants are said to have played their most dramatic role.

The timing did not prove how the bone arrived at Colina de los Quemados, but it firmly placed the animal in the right historical window. The bone was not a medieval curiosity or a later import. It belonged to the era when elephants marched alongside armies.

A Battlefield Without a Name

The researchers are careful not to overstate what they know. The precise historical event linked to the bone remains unclear. No ancient text describes an elephant dying at this exact location. Yet the surrounding evidence tells its own story.

The same destruction layer contained artillery projectiles, along with coins and ceramics confirmed to be associated with military use. Stone shots fired from lithoboloi or petroboloi, and bolt projectiles from torsion engines such as the oxybeles or scorpio, point to organized warfare rather than accidental damage.

The authors explain that such projectiles are “one of the principal archaeological indicators of military activity” during this period. Their presence suggests siege warfare or open battlefield conflict, both consistent with accounts of the Second Punic War in the Iberian Peninsula.

In that violent context, an elephant bone feels less out of place.

Could It Have Been a Souvenir?

The team considered alternative explanations. Perhaps the bone was brought to Córdoba as a trade good or a souvenir, carried far from its original setting. Ancient people did transport exotic items, and elephants were rare and remarkable animals.

But the researchers found this explanation unconvincing. A single carpal bone, they note, would not have been particularly useful or attractive. It lacks the visual drama of a tusk or the symbolic power of an intact skull. As an object of trade or display, it makes little sense.

Given the military artifacts and destruction surrounding it, the simpler explanation remains the most compelling. The bone likely belonged to an elephant that was physically present during a moment of conflict.

A Small Bone with Heavy Meaning

The authors are cautious but clear in their conclusion. The elephant carpal from Colina de los Quemados “may constitute one of the scarce instances of direct evidence on the use of these animals during Classical Antiquity,” not just in Spain, but in Western Europe as a whole.

It is a modest object. It does not confirm every detail of Hannibal’s campaigns, nor does it resolve debates about routes or tactics. But it does something quietly powerful. It bridges the gap between story and soil.

For the first time, a war elephant from the Punic Wars is no longer just an image on a coin or a line in a text. It is a physical presence, measured, dated, and placed within a violent human landscape.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it reminds us how fragile the boundary is between legend and evidence. For generations, war elephants were accepted largely on faith in ancient authors and artists. Now, a single bone adds weight to those voices, grounding them in material reality.

It also shows how archaeology works at its most human scale. Not through spectacular skeletons or dramatic monuments, but through fragments that survive by chance. A bone beneath a collapsed wall. A clue preserved because it was overlooked, buried, and forgotten.

Finally, the discovery deepens our understanding of the Second Punic War as something that unfolded not just in texts, but in real landscapes filled with fear, noise, and living creatures swept into human conflict. Elephants were not just symbols. They were animals with bodies, bones, and vulnerabilities, caught in wars that reshaped history.

In Córdoba, one of those bodies left behind a small piece of itself. More than two thousand years later, that fragment speaks.

Study Details

Rafael M. Martínez Sánchez et al, The elephant in the oppidum. Preliminary analysis of a carpal bone from a Punic context at the archaeological site of Colina de los Quemados (Córdoba, Spain), Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2026.105577