Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a disease that silently lurks within the digestive system, causing chronic inflammation and painful ulcers in the lining of the large intestine. It’s one of the most common inflammatory bowel diseases, yet despite years of research, scientists have struggled to pinpoint the exact cause. The disease, believed to be an autoimmune condition, causes symptoms that range from persistent diarrhea to rectal pain and bleeding, but the trigger that sends the immune system into overdrive has remained elusive—until now.

In a breakthrough study, researchers led by Fangyu Wang, Xuena Zhang, and Minsheng Zhu from Nanjing University have uncovered a potentially game-changing discovery. They have identified a bacterial toxin that seems to destroy key immune cells, leaving the gut vulnerable to the attacks that drive UC. Published in the journal Science, this discovery may provide the first clear explanation of how ulcerative colitis takes root in the body—and it could point the way toward a new type of treatment.

An Unexpected Culprit: Bacterial Toxins at the Heart of the Problem

The connection between bacteria and the immune system has long been known. We all carry a vast community of microbes inside our guts, some helpful and some potentially harmful. However, until this recent study, the role of these microbes in UC remained poorly understood. What if the real problem wasn’t the immune system turning against the body, but rather a hidden threat, a microscopic villain, undermining the system from within?

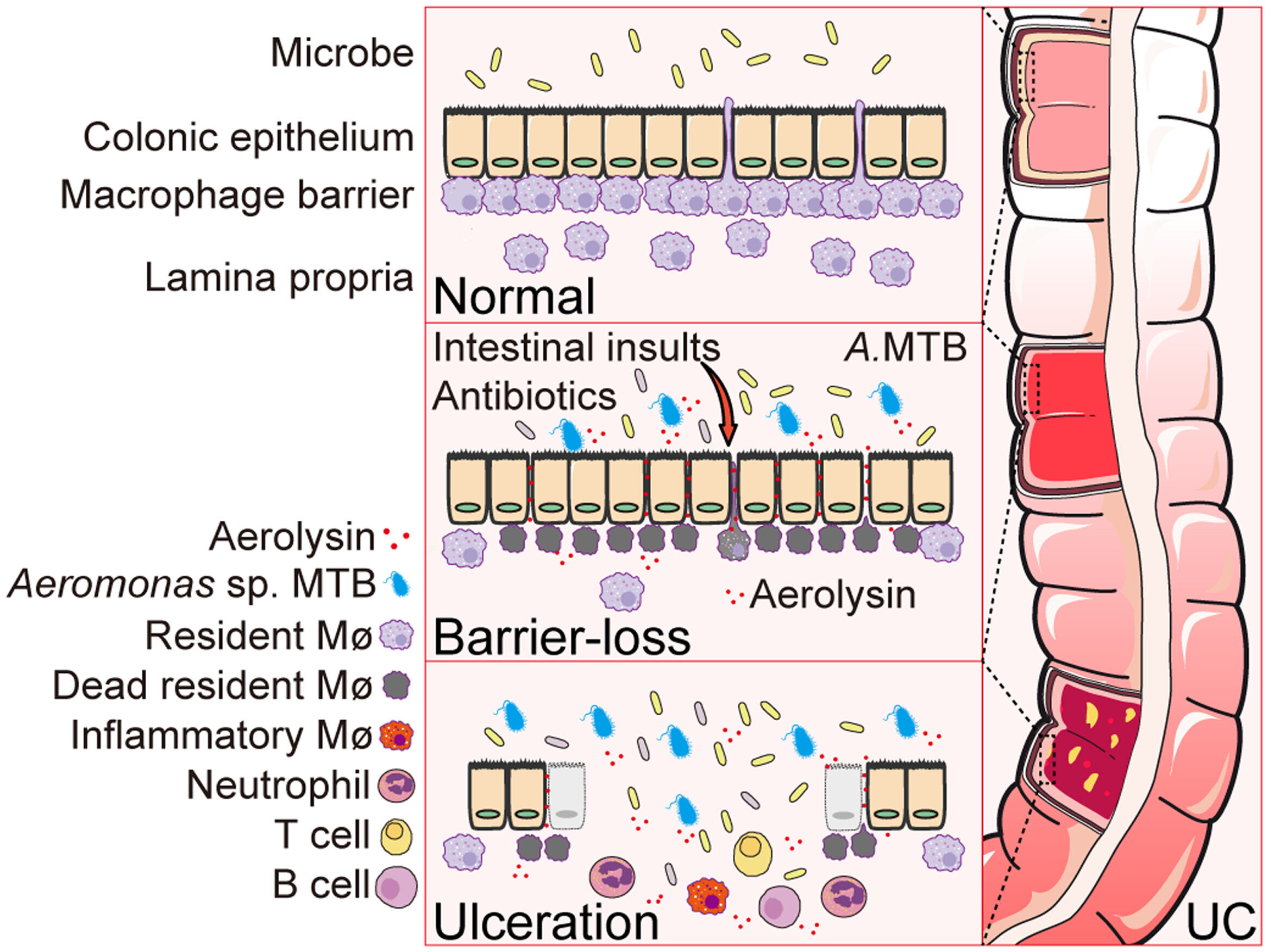

The research team’s investigation began with an important clue: previous studies had shown that macrophages, a type of immune cell that plays a critical role in protecting the gut lining, were largely absent in the gut barrier of people with UC. Macrophages are the body’s defenders, constantly on patrol to eliminate pathogens and debris. Without these immune sentinels, the gut is left exposed and vulnerable to inflammation. But why were these cells missing?

In a quest to solve this puzzle, the team turned their attention to bacteria. They theorized that something might be actively destroying these crucial macrophages, sabotaging the gut’s defenses. To test this, they analyzed fecal samples from both UC patients and healthy individuals, searching for any clues that might explain the absence of macrophages.

What they discovered was startling: a potent toxin called aerolysin, produced by a type of bacteria in the Aeromonas genus. Aerolysin was found in 72% of the UC patient samples, compared to only 12% of healthy individuals. This alarming difference suggested that the presence of this toxin could be tied to the onset of the disease.

The Destructive Power of Aerolysin

Aerolysin is no ordinary substance. It’s a toxin that attacks the very cells that protect the gut, including the vital macrophages. Once aerolysin encounters its target, it punches holes in the cell’s outer membrane, leading to rapid and often catastrophic cell death. In the case of UC, this means the immune system’s first line of defense is being obliterated, leaving the gut open to the inflammation that causes painful symptoms like bleeding and ulcers.

To explore this theory further, the team dubbed the specific strain of bacteria that produces aerolysin the “macrophage-toxic bacteria” (MTB). The name was fitting, as this strain seemed to be actively killing off the immune cells that are supposed to keep the gut healthy.

But the team wasn’t content with simply identifying the presence of aerolysin. They needed to prove that it was this toxin, not just the bacteria itself, that was causing the damage. And so, they turned to mice models that had been chemically induced with colitis—an animal model often used to study UC.

When they infected these mice with the MTB bacteria, the results were clear and alarming. The mice exhibited symptoms similar to UC—weight loss, bleeding, and ulceration of the intestines—all of which worsened as the bacterial infection took hold. However, when the researchers introduced a genetically engineered version of the bacteria that couldn’t produce aerolysin, the symptoms didn’t worsen at all. It was a clear sign that it wasn’t the bacteria itself causing the damage, but the toxin they were releasing.

A Glimmer of Hope: Targeting the Toxin to Treat UC

As promising as this discovery was, the team wasn’t done yet. They wanted to see if they could reverse the damage caused by aerolysin. To do this, they administered anti-aerolysin antibodies to the mice that had been infected with the macrophage-toxic bacteria. The results were striking—symptoms of colitis in the mice were alleviated.

This is where the potential of this research really shines. At present, UC treatments typically involve suppressing the immune system, which can leave patients vulnerable to infections and other complications. But what if there was a way to specifically target the cause of the inflammation—without affecting the entire immune system?

As the team discusses in their paper, “Our findings highlight how microbes may contribute to UC pathogenesis and suggest that targeting bacterial virulence factors could be a therapeutic strategy for UC.” This could pave the way for more precise treatments that target the bacterial toxins responsible for the disease, rather than the broad and often harmful immune suppression that patients currently endure.

Why This Research Matters

The implications of this study are far-reaching, not just for those suffering from ulcerative colitis, but for the broader field of autoimmune diseases. For years, scientists have known that the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in health, but understanding the exact mechanisms has been challenging. This discovery provides a tangible link between bacterial toxins and the destruction of key immune cells, offering a new perspective on how diseases like UC develop.

If these findings hold true in humans, it could revolutionize how we think about and treat UC. Rather than relying on treatments that suppress the immune system, which can have wide-ranging side effects, doctors could potentially use therapies that target the specific bacterial toxins causing the damage. This would be a far more targeted and effective approach, with the potential to reduce symptoms without the harsh consequences of immune suppression.

Moreover, this research may open the door to similar approaches for other autoimmune diseases. By identifying bacterial factors that contribute to immune system malfunctions, scientists could develop new strategies for preventing or managing a variety of conditions linked to immune dysfunction.

Ultimately, this study is more than just a scientific breakthrough; it’s a beacon of hope for the millions of people living with ulcerative colitis and other autoimmune diseases. The idea that we might be able to treat these conditions by targeting the root cause—bacterial toxins—represents a major leap forward in our understanding and treatment of these chronic, often debilitating diseases. As we look to the future, this discovery could mark the beginning of a new era in precision medicine, where treatments are tailored to target the true causes of disease at their source.

More information: Zhihui Jiang et al, An Aeromonas variant that produces aerolysin promotes susceptibility to ulcerative colitis, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adz4712

Sonia Modilevsky et al, A bacterial toxin disarms gut defenses against inflammation, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.aec7924