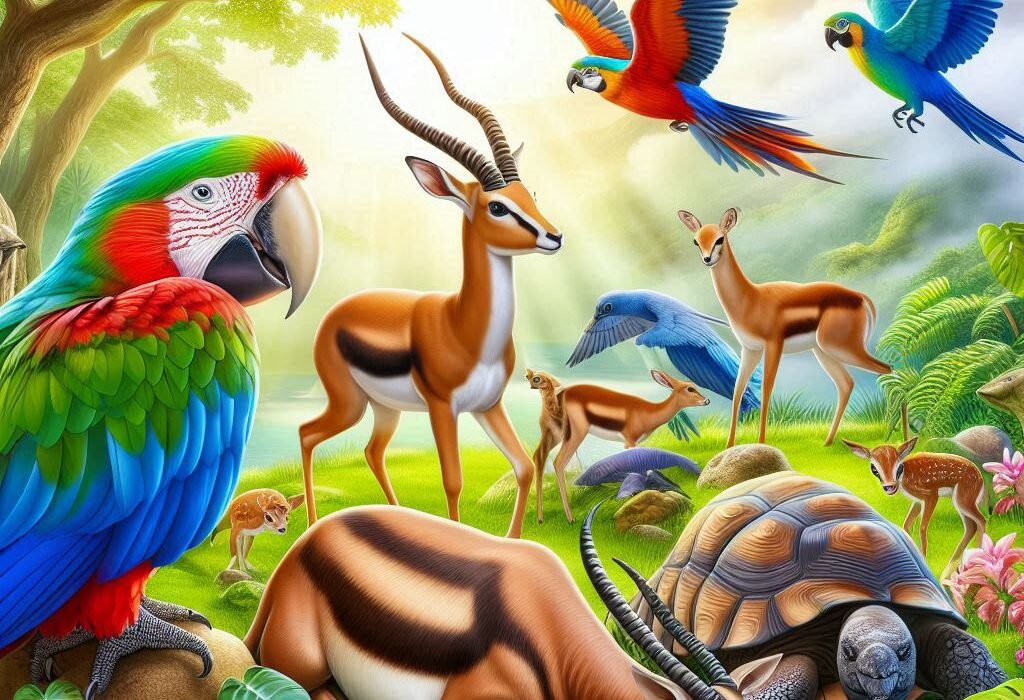

Picture a squirrel perched on the edge of a tree branch, its fluffy tail balancing it against the wind. In its front paws, it clutches an acorn. Watch closely: the squirrel isn’t just holding it with claws like you might expect—it’s using something subtler, something almost human. Its thumbs have flat, smooth nails, not the curved claws that arm its other fingers. With these tiny thumbnails, it steadies the nut, rotates it, and peels it open with a precision that feels almost deliberate.

This small detail might seem trivial, but it hides a remarkable story about evolution, survival, and the success of one of Earth’s most prolific animal groups: the rodents. For centuries, scientists had noticed that some rodents have thumbnails, while others don’t. But until recently, no one had traced this pattern across the sprawling rodent family tree, a lineage that includes nearly half of all mammal species alive today.

Now, thanks to a sweeping study published in Science, we are beginning to understand what these tiny thumbnails reveal about how rodents conquered the world.

A Question Nobody Thought to Ask

It’s easy to assume that everything about familiar animals like squirrels is already well studied. Yet even seasoned rodent experts admit they were surprised.

“When I talk with people about this research, I always start by asking, ‘Did you know rodents have thumbnails?’ Most people don’t. I didn’t,” says Rafaela Missagia, research associate at Chicago’s Field Museum and assistant professor at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. “I had studied rodents for years, and I didn’t know anything about their nails until I started working on this project.”

That sense of wonder and humility became the spark for a research collaboration. The Field Museum is home to one of the world’s most expansive mammal collections, and because rodents make up about 40% of mammal diversity, the museum has thousands of specimens, each carrying hidden details about anatomy and evolution.

It was here that neuroscientist Gordon Shepherd of Northwestern University saw an opportunity. Scientists already knew that some rodents had thumbnails, some had clawed thumbs, and others lacked thumbs altogether. But no one had assembled the big picture. Could thumbnails be a clue to why rodents are so successful?

A Museum Becomes a Time Machine

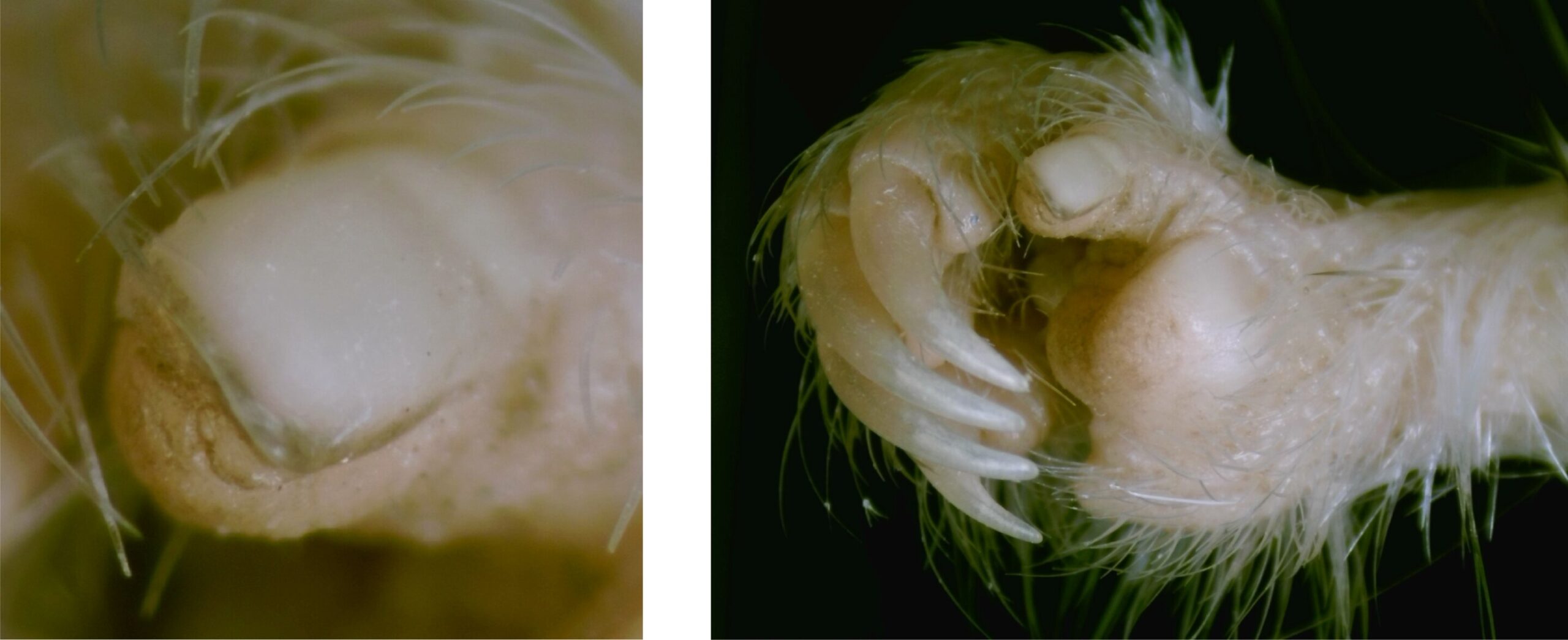

To answer that question, the team embarked on a meticulous survey. They examined hundreds of preserved rodent skins and skeletons at the Field Museum, carefully noting whether each specimen’s thumb bore a flat nail, a claw, or nothing at all.

“There are more than 530 genera of rodents, containing over 2,500 species,” explains Anderson Feijó, curator of mammals at the Field Museum and one of the study’s authors. “We looked at 433 of those genus groups from across the rodent family tree.”

What they found was striking: the overwhelming majority—about 86% of the genera studied—had species with thumbnails.

But observation was only the beginning. To make sense of this evolutionary pattern, the researchers combined the anatomical survey with data about behavior. They turned to sources ranging from field guides to photographs on the citizen-science platform iNaturalist, compiling evidence about how rodents use their hands.

The result was a reconstructed family tree showing not only which rodents had thumbnails, but also how they handled their food.

Thumbs for Dining

The connections that emerged told a clear story. Rodents with thumbnails were much more likely to grasp and manipulate food with their hands, while those without thumbnails often relied on their mouths alone.

Guinea pigs, for example, lack thumbs entirely and tend to nibble food directly without holding it. Squirrels, on the other hand, skillfully rotate nuts in their paws, positioning them with the help of their thumbnails. The thumbnail functions like a stabilizing pad, allowing for finer control than a claw could provide.

This may sound like a small evolutionary tweak, but it had enormous consequences. Nuts and seeds are high-energy food sources, but they are also hard to crack. Animals capable of delicately maneuvering them had access to a treasure trove of nutrition that less dexterous creatures couldn’t exploit.

The researchers suggest that this ability might have given rodents a crucial edge. By mastering nuts and seeds, thumbnail-bearing rodents could thrive in new habitats, expand their diets, and ultimately diversify into the thousands of species we see today.

An Ancient Adaptation

The study didn’t just reveal how thumbnails help modern rodents. It also pushed the timeline of thumbnails far back in evolutionary history.

The team’s analysis suggests that the earliest common ancestor of all living rodents likely had thumbnails too. In other words, thumbnails weren’t a late addition to the rodent toolkit—they were present at the very root of the lineage.

This means that for tens of millions of years, thumbnails may have been quietly shaping the course of rodent evolution. From forests to grasslands to deserts, rodents with nimble hands could exploit resources that others couldn’t. Their thumbnails may have been one of the subtle, overlooked innovations that helped rodents spread across every continent except Antarctica.

Beyond Eating: Life in Trees and Underground

Food wasn’t the only factor at play. The researchers also discovered a link between thumbnails and lifestyle.

Primates, which are our closest relatives, mostly have nails instead of claws, and they are often tree-dwellers. The team wondered whether a similar pattern existed in rodents. The data confirmed their hunch: rodents with thumbnails were more likely to live above ground or in trees, while those that dig—fossorial rodents—were more likely to have claws on their thumbs instead.

This makes sense. Digging demands sharp, strong claws for tearing into soil. But life among branches rewards dexterity, and thumbnails offer the fine-tuned grip needed to steady a nut or balance on bark.

In this way, thumbnails are more than feeding tools. They are fingerprints of ecology, revealing how rodents interact with their environments.

A Case of Convergent Evolution

One of the most fascinating aspects of the study is how thumbnails in rodents echo a familiar story in primates. Humans and our primate relatives also have nails on our thumbs instead of claws. But the resemblance is not due to shared ancestry. Instead, it’s an example of convergent evolution, in which two unrelated groups arrive at a similar solution to a problem.

For primates, nails likely evolved to support life in trees and manipulation of objects, paving the way for the extraordinary dexterity that would eventually allow humans to make tools, write, and build civilizations. For rodents, thumbnails may have been the gateway to their own success, though on a very different evolutionary path.

The parallel is striking. It suggests that across very different lineages, flat nails can open the door to new behaviors and new opportunities.

The Hidden Value of Museum Collections

Perhaps the most inspiring lesson from this research is not just about rodents, but about science itself. None of this discovery would have been possible without the vast archives of preserved specimens in museums.

“Museum collections are an endless source of discoveries,” says Feijó. “For all of the rodents that were used in this study, I bet none of the collectors would have imagined that someone someday would be studying those rodents’ thumbnails.”

Specimens collected decades or even centuries ago are still yielding new insights, reminding us that science is not only about looking forward, but also about revisiting what we already have with fresh eyes and fresh questions.

In that sense, the squirrel’s thumbnail is more than a curiosity. It is a symbol of hidden stories waiting to be uncovered—stories that may reshape how we see even the most ordinary animals.

A World Changed by Tiny Details

It’s easy to overlook small features like a thumbnail. Yet evolution is built on such details. A flat nail instead of a claw may seem minor, but in the grand sweep of time, it can open doors to new behaviors, new habitats, and new evolutionary paths.

Squirrels holding their acorns are not just charming scenes of autumn—they are the visible echoes of ancient adaptations that allowed rodents to thrive across the planet. Their thumbnails, silent and unassuming, are part of a legacy that helped shape ecosystems everywhere.

And so, next time you see a squirrel perched on a branch, pausing to rotate a nut between its paws, take a closer look. Hidden in that tiny gesture is a story of survival, ingenuity, and the power of evolution. A thumbnail may be small, but in the hands of a rodent, it changed the world.

More information: Evolution of thumbnails across Rodentia, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.ads7926