Across grocery store aisles and in lunchboxes, vending machines, and kitchen cupboards, ultra-processed foods have become an everyday staple for millions of Canadians. From sugary breakfast cereals to frozen pizzas, salty chips, and microwavable meals, these factory-crafted concoctions are convenient, affordable, and heavily marketed. But beneath their colorful packaging and irresistible flavors lies a darker reality—one that a new landmark Canadian study has brought into sharp focus.

Researchers at McMaster University have published groundbreaking findings confirming what many health experts have long suspected: ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are directly and significantly linked to a range of poor health outcomes. This is the first Canadian study of its kind to leverage population-based biomarker data to uncover the insidious ways UPFs are impacting the human body.

Digging Into the Data: A Canadian First

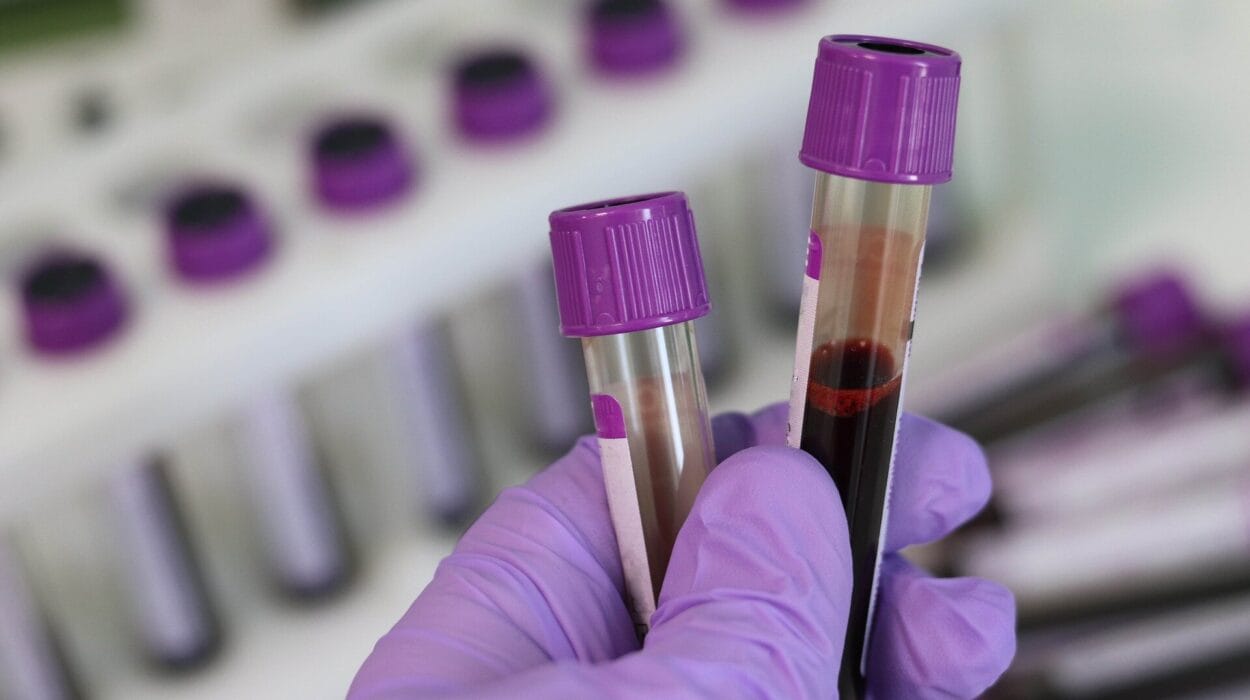

The McMaster team analyzed data from over 6,000 adults drawn from the Canadian Health Measures Survey, conducted by Health Canada and Statistics Canada. This dataset is a goldmine of national health information, offering a rare window into how lifestyle choices translate into biological realities.

Participants, representing a cross-section of Canada in terms of age, income, education, and geographic location, completed detailed dietary questionnaires and were subsequently examined in mobile health clinics. Blood pressure, cholesterol levels, waist circumference, insulin levels, and other key biomarkers were recorded and analyzed. What emerged from this trove of data was a clear, consistent, and troubling pattern.

A Cascade of Consequences

Those who consumed the highest amounts of ultra-processed foods were more likely to be men, have lower income and education levels, and eat fewer fruits and vegetables. But most strikingly, they also had dramatically higher levels of body fat, blood pressure, insulin, and triglycerides. Their cholesterol profiles were worse, their waistlines wider, and their metabolic markers more concerning.

And here’s the kicker: these links held strong even after accounting for how much food they ate, how much they exercised, whether they smoked, and even their socioeconomic status.

“Even when we adjusted for BMI, which is usually a big confounder in nutrition studies, the associations between UPF consumption and poor health outcomes remained strong,” said Dr. Anthea Christoforou, senior author of the study and an assistant professor in the Department of Kinesiology at McMaster. “This suggests that something about the UPFs themselves—beyond just making us gain weight—is contributing to disease.”

More Than Calories: The Inflammatory Truth

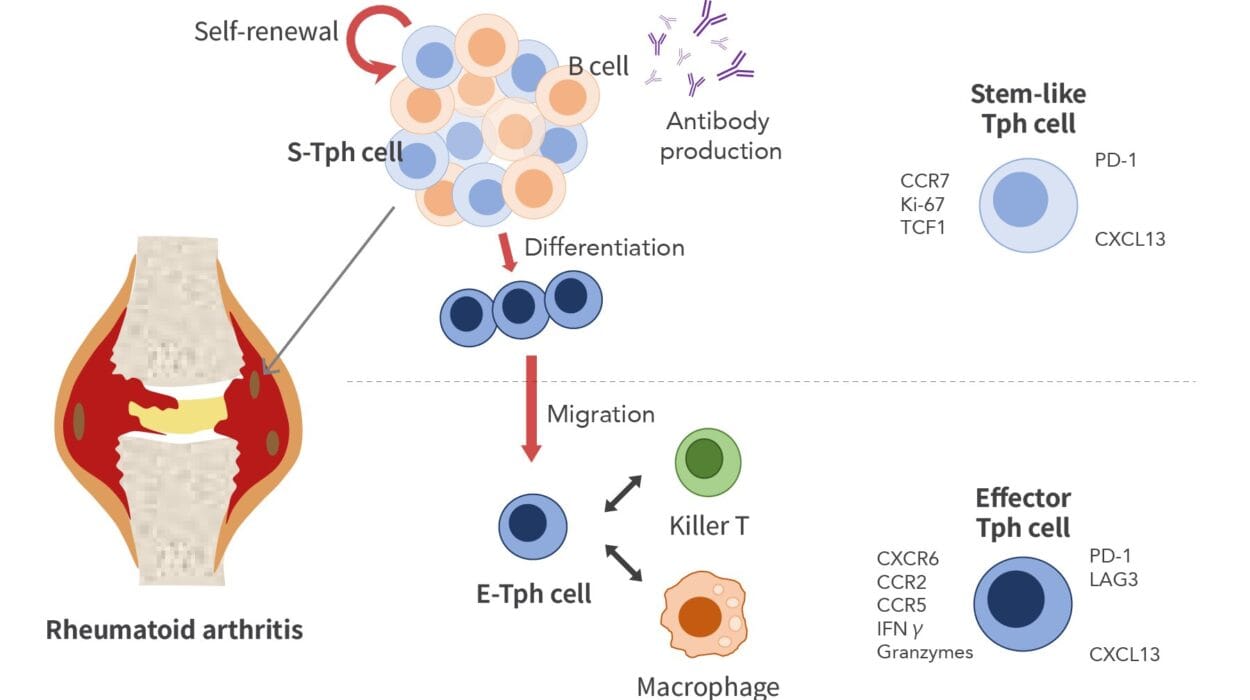

One of the most revealing aspects of the study was its look at inflammation. Researchers measured C-reactive protein (CRP), a substance produced by the liver in response to inflammation, as well as white blood cell counts. Both were elevated in people who consumed high levels of UPFs. This means these foods aren’t just passively contributing to weight gain—they’re actively triggering inflammatory responses in the body.

“In a sense, this suggests that our bodies are seeing these foods as non-foods, as some kind of other element,” explained Christoforou. “They may be kicking off immune responses much like bacteria or toxins would.”

Chronic inflammation is a known precursor to a host of diseases—heart disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, and even neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s. The idea that daily consumption of convenient snacks and meals could be fueling such fires in the body is sobering.

What Makes a Food Ultra-Processed?

Ultra-processed foods are not simply “junk food” or “fast food.” They are industrial formulations made mostly from substances extracted from foods (like oils, fats, starches, sugars, and proteins), or synthesized in laboratories (like artificial colors, sweeteners, preservatives, emulsifiers, and flavor enhancers). They are designed to be hyper-palatable, convenient, and shelf-stable—but rarely nutritious.

Typical examples include sodas, flavored yogurts, boxed cake mixes, reconstituted meat products, and ready-to-heat meals. These products often bear little resemblance to their original ingredients and are engineered to be consumed quickly, without preparation, and often in large quantities.

A Global Takeover of the Plate

Canada is far from alone in its struggle with UPFs. In fact, the Canadian experience reflects a global trend. In middle- and high-income countries, UPFs are becoming the dominant source of calories. These foods now account for over 50% of total dietary energy intake in countries like the U.S., U.K., and Australia. Canada is not far behind.

According to the McMaster study, Canadian participants consumed an average of more than three servings of UPFs per day. Those in the highest consumption group averaged six servings daily—a number that likely underestimates true intake, given the ubiquity of hidden additives and refined ingredients in many everyday foods.

Who Eats the Most—and Why?

The study also highlights social patterns in UPF consumption. Individuals with lower income and education levels were more likely to eat greater quantities of ultra-processed foods. This is hardly surprising—UPFs are generally cheaper, require less preparation time, and are more aggressively advertised to budget-conscious consumers.

However, the researchers caution against assuming that only lower-income Canadians are at risk. “Ultra-processed foods are impacting health across all socioeconomic groups,” said Angelina Baric, a graduate student and co-author of the study. “While some populations are more exposed to these foods, our findings show that the health risks persist independently of income and education.”

This observation underscores the need for population-wide solutions, not just targeted interventions. The UPF problem is systemic—and so must be the response.

Beyond Obesity: A Metabolic Menace

One of the most compelling aspects of the McMaster study is that it looks beyond weight gain. While it’s well-established that UPFs are linked to rising rates of overweight and obesity, this research shows that even people with normal weight can experience harmful metabolic effects from high UPF intake.

This includes insulin resistance, dyslipidemia (abnormal cholesterol levels), and systemic inflammation. In other words, a person may appear outwardly healthy while silently developing risk factors for heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions—all because of what’s on their plate.

“It’s not just about counting calories or losing weight,” Christoforou emphasizes. “It’s about what those calories are made of, how those foods are engineered, and how they interact with our biology at the molecular level.”

The Hidden Mechanics of Harm

But how exactly do UPFs trigger these effects? The study’s authors suggest several possible mechanisms. Additives such as emulsifiers and artificial sweeteners may alter the gut microbiome, increasing permeability and allowing toxins to enter the bloodstream. Industrial fats and sugars may promote insulin resistance and fatty liver disease. Even the texture and speed of consumption may play a role in metabolic disruption.

What’s more, UPFs often displace healthier whole foods from the diet—foods rich in fiber, antioxidants, and phytonutrients that help regulate inflammation, blood sugar, and digestion.

Policy, Not Just Personal Choice

Health Canada currently recommends limiting processed food intake, but such advice is often drowned out by the marketing clamor of the food industry. Experts argue that more forceful policies are needed to curb UPF consumption at the population level.

This includes clearer labeling, restrictions on advertising to children, taxes on certain products, subsidies for fruits and vegetables, and changes to the way food is priced, packaged, and promoted.

“The food environment we live in is engineered for UPF consumption,” Christoforou notes. “It’s not enough to tell people to eat better. We have to make it easier—and more affordable—for them to do so.”

The Road Ahead: From Discovery to Action

The McMaster team is not stopping here. Their next steps include studying UPF consumption in children, exploring links to fertility and hormonal health in women, and examining the biological pathways through which these foods induce inflammation and metabolic chaos.

They are also investigating the role of affordability and local food environments in driving dietary choices. Ultimately, their goal is to inform fair, inclusive public health strategies that help all Canadians eat—and live—better.

“This is not just a health issue,” Baric concludes. “It’s a social issue. It’s an economic issue. It’s an environmental issue. The way we produce, sell, and consume food has to change—because our health depends on it.”

Reference: Angelina Baric et al, Ultra-processed food consumption and cardiometabolic risk in Canada: a cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian health measures survey, Nutrition & Metabolism (2025). DOI: 10.1186/s12986-025-00935-y