In the vast silence of the universe, where distances are measured in billions of light-years and time itself stretches toward incomprehensible beginnings, astronomers expected simplicity at the largest scales. The modern cosmological picture rests on a powerful assumption: when viewed broadly enough, the universe should look the same in every direction. This principle, known as cosmic isotropy, lies at the heart of contemporary cosmology. Yet, hidden within the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, scientists have discovered a puzzling feature that seems to challenge this expectation. It is an anomaly so strange, so unexpected, that it earned a provocative nickname—the “Axis of Evil.”

The Axis of Evil is not a physical structure, nor is it a cosmic object that can be pointed to in the sky. Instead, it is a pattern embedded in the cosmic microwave background, the oldest light in the universe. Its name reflects both its controversial nature and the unease it provokes among cosmologists. If this alignment is real and not an artifact of data or chance, it may hint at physics beyond our current understanding of the universe. The story of the Axis of Evil is a story of precision measurement, statistical surprise, theoretical discomfort, and the profound human struggle to interpret the cosmos honestly.

The Cosmic Microwave Background: A Map of the Infant Universe

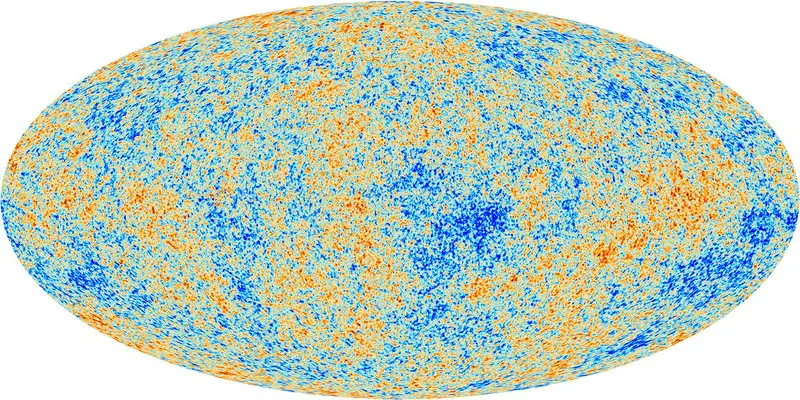

To understand the Axis of Evil, one must first understand the cosmic microwave background, often abbreviated as the CMB. This faint radiation fills the universe uniformly, bathing all of space in microwaves that correspond to a temperature just a few degrees above absolute zero. The CMB is not merely background noise; it is a fossil imprint of the universe when it was only about 380,000 years old.

Before this time, the universe was a hot, dense plasma of charged particles and radiation. Photons scattered constantly off electrons, preventing light from traveling freely. As the universe expanded and cooled, protons and electrons combined to form neutral hydrogen atoms. With fewer charged particles to scatter from, photons were suddenly able to move freely through space. Those photons, stretched by billions of years of cosmic expansion, are what we observe today as the CMB.

Importantly, the CMB is not perfectly uniform. Tiny temperature fluctuations, at the level of one part in 100,000, are imprinted across the sky. These fluctuations encode a wealth of information about the early universe, including the seeds of galaxies and the geometry of spacetime itself. Mapping and analyzing these patterns has become one of the most powerful tools in cosmology.

The Expectation of Cosmic Uniformity

The standard cosmological model assumes that, on the largest scales, the universe is both homogeneous and isotropic. Homogeneity means that the universe has roughly the same properties at every location, while isotropy means it looks the same in every direction. These assumptions are not arbitrary; they are strongly supported by observations and simplify the equations of general relativity when applied to cosmology.

Inflationary theory, which posits a brief period of extremely rapid expansion in the early universe, provides a compelling explanation for isotropy. Inflation smooths out any initial irregularities, stretching tiny regions to cosmic scales and erasing directional preferences. As a result, the CMB should exhibit random fluctuations without any preferred orientation when examined statistically.

While small anomalies and random alignments are expected, any large-scale directional pattern would be surprising. Such a pattern could imply either an unrecognized systematic error in measurements or something fundamentally new about the universe. It is against this backdrop of expectation that the Axis of Evil emerged.

Discovering the Anomaly in the Cosmic Map

The first hints of the Axis of Evil appeared in data from the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, commonly known as WMAP. Launched in 2001, WMAP was designed to measure the temperature fluctuations of the CMB with unprecedented precision. When the first full-sky maps were released, cosmologists began decomposing the data into spherical harmonics, a mathematical technique that separates patterns by their angular scale.

The largest-scale fluctuations in the CMB are described by the lowest multipoles, particularly the quadrupole and octopole components. These correspond to temperature variations spanning vast regions of the sky. In a statistically isotropic universe, the orientations of these multipoles should be random. However, analyses of the WMAP data revealed something unexpected: the quadrupole and octopole appeared to be unusually aligned with each other.

Even more unsettling, this alignment seemed to point roughly along the plane of the Solar System and toward the direction of the ecliptic. The coincidence was striking. Instead of pointing in random directions, these large-scale patterns appeared to share a common axis. Because this axis seemed to violate cherished cosmological assumptions, and because it aligned suspiciously with local reference frames, it was half-jokingly dubbed the “Axis of Evil.”

Why the Alignment Is So Disturbing

The discomfort surrounding the Axis of Evil arises from several interconnected concerns. First, if the alignment is intrinsic to the universe, it challenges the assumption of isotropy. A preferred direction in the universe would undermine one of the foundational pillars of cosmology and suggest new physics beyond the standard model.

Second, the alignment’s proximity to the ecliptic plane raises the possibility of contamination. The Solar System is filled with foreground signals, including emission from dust and charged particles. If these foregrounds were not perfectly removed from the data, they could imprint spurious patterns that mimic cosmic anomalies.

Third, the statistical significance of the alignment is subtle. Cosmology deals with only one observable universe, which complicates statistical interpretation. Determining whether an anomaly is genuinely improbable or simply a rare but acceptable fluctuation is inherently challenging.

Despite these difficulties, the Axis of Evil has persisted as a topic of debate, refusing to disappear under closer scrutiny.

Statistical Significance and the Problem of Cosmic Variance

One of the greatest challenges in evaluating the Axis of Evil is cosmic variance. Because we can observe only one universe, we have only one realization of the largest-scale fluctuations. At small scales, many independent regions can be compared, allowing robust statistics. At the largest scales, however, the number of independent modes is very limited.

This limitation means that even genuinely random fluctuations can appear unusual. Assessing the probability of a particular alignment requires assumptions about what constitutes a meaningful anomaly. Different statistical methods can yield different conclusions about significance, ranging from modest tension to serious inconsistency with isotropy.

Some studies have estimated that the alignment has a probability of occurring by chance at the level of a few percent. Others argue that once one accounts properly for selection effects and a posteriori choices, the significance diminishes substantially. The debate highlights a deep epistemological challenge in cosmology: distinguishing between chance and necessity when dealing with a single cosmic sample.

Confirmation and Controversy from Planck Data

The launch of the Planck satellite by the European Space Agency provided an opportunity to revisit the Axis of Evil with improved data. Planck measured the CMB with higher resolution and sensitivity than WMAP, and it employed different instruments and scanning strategies, reducing the likelihood of shared systematic errors.

When Planck’s results were released, cosmologists scrutinized the large-scale anomalies with renewed intensity. The alignment between the quadrupole and octopole persisted in the Planck data, lending credibility to the idea that it was not merely an artifact of WMAP. However, the interpretation remained contentious.

Planck analyses emphasized caution, noting that uncertainties in foreground subtraction and the limited statistical power at large scales complicate definitive conclusions. While the Axis of Evil could not be dismissed outright, neither could it be confidently declared a sign of new physics. Instead, it occupied an uneasy middle ground between anomaly and artifact.

Foregrounds and Systematic Effects

A crucial question in the Axis of Evil debate concerns the role of foreground contamination. The CMB signal must be extracted from a sky filled with emissions from the Milky Way, interplanetary dust, and extragalactic sources. Sophisticated algorithms are used to separate these components, but no method is perfect.

Because the Axis of Evil aligns suspiciously with the ecliptic, critics argue that residual Solar System effects may be responsible. Emissions from zodiacal dust, instrumental scanning patterns tied to the satellite’s orbit, or subtle calibration issues could imprint artificial alignments.

Defenders of the anomaly counter that extensive tests have been conducted to assess these possibilities. Different foreground removal techniques, frequency bands, and data subsets have been analyzed, with the alignment often remaining visible. While this does not conclusively rule out systematics, it suggests that the anomaly is robust against many sources of error.

Theoretical Explanations Beyond Standard Cosmology

If the Axis of Evil is indeed a real feature of the universe, it demands explanation. Several theoretical ideas have been proposed, each with profound implications.

One possibility is that the universe is not perfectly isotropic due to unusual initial conditions. In some models, inflation may not have lasted long enough to erase all directional information, leaving a faint imprint on the largest scales. Such scenarios challenge the simplest versions of inflation but remain compatible with certain extensions.

Another idea involves cosmic topology. If the universe has a nontrivial global shape, such as being finite but unbounded, it could produce correlations and alignments in the CMB. In such models, light could wrap around the universe, imprinting patterns that break isotropy. While intriguing, these models must confront strong observational constraints.

More radical explanations invoke anisotropic cosmologies, in which the expansion rate of the universe differs slightly along different directions. These models are tightly constrained by data but not entirely ruled out. Even a tiny anisotropy in expansion could, in principle, influence the largest-scale CMB patterns.

The Role of Chance and Human Pattern Recognition

An often-overlooked aspect of the Axis of Evil controversy is the human tendency to see patterns. Humans are exceptionally skilled at detecting alignments and structures, sometimes even where none exist. In a data-rich field like cosmology, the risk of overinterpreting random features is ever-present.

Some researchers argue that the Axis of Evil emerged partly because cosmologists looked for anomalies after the fact. Once an unusual feature was noticed, it became the focus of intense scrutiny, potentially exaggerating its perceived significance. This does not mean the anomaly is illusory, but it underscores the importance of rigorous statistical discipline.

The debate thus reflects a broader tension in science between openness to surprise and resistance to self-deception. Cosmology, dealing with the ultimate scale of reality, magnifies this tension.

Philosophical Implications of a Preferred Direction

If future evidence were to confirm the Axis of Evil as a genuine cosmological feature, the implications would extend beyond physics. A preferred direction in the universe would challenge long-held philosophical assumptions about symmetry and uniformity. It would force a reexamination of the Copernican principle, which holds that Earth and its surroundings do not occupy a special position in the cosmos.

Such a revision would not imply a return to geocentrism, but it would suggest that the universe possesses a subtle structure that distinguishes directions on the largest scales. This would raise profound questions about why the universe has the properties it does and whether these properties are the result of deeper laws or historical contingencies.

Even the name “Axis of Evil,” though informal, reflects the emotional weight of the issue. It captures the sense that something seemingly malevolent has crept into an otherwise elegant and symmetric cosmic picture.

The Current State of the Mystery

As of today, the Axis of Evil remains unresolved. It is neither universally accepted as evidence of new physics nor dismissed as a mere artifact. Instead, it occupies a liminal space, a reminder of the limits of our knowledge and the challenges inherent in studying the universe at the largest scales.

Future observations may shed light on the issue. Improved measurements of CMB polarization, deeper surveys of large-scale structure, and new theoretical insights could help clarify whether the alignment is cosmological in origin or the result of subtle biases. Advances in data analysis techniques may also refine our ability to assess statistical significance in a single-universe context.

Regardless of its ultimate resolution, the Axis of Evil has already played an important role in cosmology. It has forced scientists to scrutinize their assumptions, improve their methods, and confront the possibility that the universe may be more complex than previously imagined.

The Axis of Evil as a Symbol of Scientific Humility

Beyond its technical details, the Axis of Evil serves as a powerful symbol of scientific humility. Cosmology has achieved extraordinary success, constructing a coherent narrative of cosmic history supported by diverse observations. Yet even within this triumph lies uncertainty, ambiguity, and the potential for surprise.

The willingness to take anomalies seriously, without prematurely embracing or dismissing them, is a hallmark of good science. The Axis of Evil exemplifies this balance. It reminds us that the universe does not owe us simplicity, and that our most cherished principles must remain open to challenge.

In the faint patterns of ancient light, we glimpse both the order and the mystery of the cosmos. Whether the Axis of Evil ultimately proves to be a statistical fluke, a systematic artifact, or a window into new physics, it stands as a testament to the enduring human desire to understand the universe honestly and deeply. In that pursuit, even uncertainty becomes a source of wonder, guiding us toward deeper questions about the nature of reality itself.