On clear nights, the Moon appears serene and familiar, a steady companion that has shaped human calendars, myths, and imagination for millennia. Its phases govern tides, its light softens darkness, and its presence feels timeless. Yet beneath this calm exterior lies a story of violence and transformation—one that reaches back to the earliest chapters of Earth’s history. Modern planetary science suggests that the Moon was born not from quiet accumulation, but from catastrophe. According to the leading hypothesis, a colossal collision between the young Earth and a Mars-sized body known as “Theia” created the debris from which our Moon formed. This idea, known as the giant impact hypothesis, is one of the most compelling narratives in planetary science, weaving together geology, physics, chemistry, and cosmic chance.

Understanding the Moon’s origin is more than an exercise in celestial history. It illuminates how planets form, how collisions shape worlds, and why Earth became a planet capable of sustaining life. The Moon is not merely Earth’s satellite; it is a fossil record of a formative event that helped define our planet’s destiny.

The Early Solar System: A Violent Nursery

To understand how the Moon may have formed, it is necessary to imagine the solar system as it existed over four billion years ago. The tranquil arrangement of planets we observe today is the outcome of a long and chaotic process. In its infancy, the solar system was a turbulent disk of gas and dust surrounding the newborn Sun. Within this disk, particles collided, stuck together, and gradually built up into larger bodies known as planetesimals.

As these bodies grew, gravity amplified their interactions. Collisions became more frequent and more energetic. Some impacts led to growth, others to fragmentation. Over tens of millions of years, this cosmic melee produced a small number of dominant planetary embryos—objects large enough to shape their surroundings. Earth was one of these embryos, still incomplete, still molten in places, and still sharing its orbital neighborhood with other sizable bodies.

In this environment, massive impacts were not rare anomalies; they were expected outcomes. The Earth itself is thought to have grown through repeated collisions, each one contributing material and energy. The formation of the Moon, within this framework, becomes a question not of whether a giant impact occurred, but of how its specific circumstances produced such a distinctive satellite.

Early Ideas About the Moon’s Formation

Before the giant impact hypothesis gained prominence, scientists proposed several competing theories to explain the Moon’s origin. Each reflected the observational evidence available at the time, and each grappled with the Moon’s unique characteristics.

One early idea suggested that the Moon formed alongside Earth from the same region of the solar nebula, a concept known as co-accretion. In this view, Earth and Moon were siblings born together. While appealing in its simplicity, this theory struggled to explain why the Moon has a much smaller iron core than Earth and a significantly lower overall density.

Another hypothesis proposed that the Moon formed elsewhere in the solar system and was later captured by Earth’s gravity. This capture theory faced serious physical challenges. Capturing a body as large as the Moon without dissipating enormous amounts of energy is extremely difficult, and the resulting orbit would likely be highly elongated rather than the relatively stable one observed today.

A third idea, the fission hypothesis, suggested that the Moon split off from a rapidly spinning early Earth. This notion was inspired by the apparent similarity between Earth’s mantle composition and lunar rocks. However, calculations showed that Earth would have needed to rotate implausibly fast for such a process to occur.

Each of these ideas contained partial truths but failed to account for the full range of evidence. The stage was set for a new hypothesis that could integrate geochemical, dynamical, and physical constraints into a coherent explanation.

The Birth of the Giant Impact Hypothesis

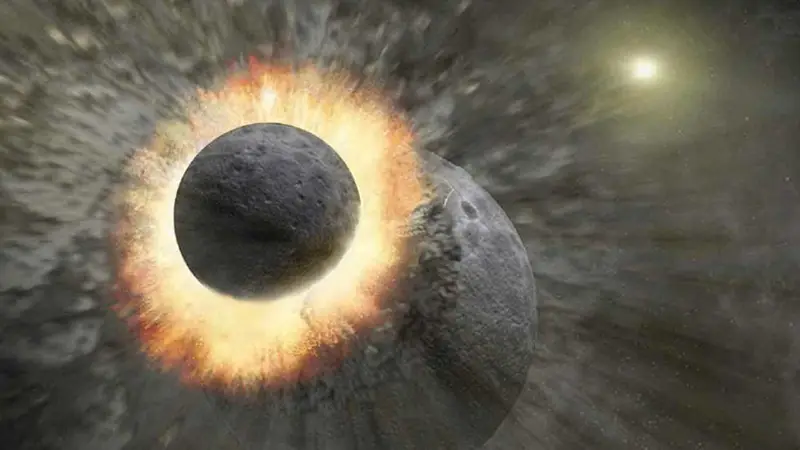

The giant impact hypothesis emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century as planetary scientists began to synthesize insights from multiple disciplines. The core idea is both dramatic and elegant: a large protoplanet, roughly the size of Mars, collided with the young Earth at an oblique angle. The impact ejected vast amounts of material into orbit around Earth, forming a disk of debris. Over time, this debris coalesced to form the Moon.

The hypothetical impactor came to be known as Theia, named after the Titan in Greek mythology who was the mother of Selene, the Moon goddess. While Theia itself is no longer present as a distinct body, its legacy may be preserved in the Moon’s composition.

Computer simulations played a crucial role in developing this hypothesis. When researchers modeled high-energy collisions between planetary bodies, they found that certain impact scenarios naturally produced Earth–Moon systems resembling the one we observe today. These models showed that an oblique impact could impart the Earth–Moon system with its current angular momentum while also explaining the Moon’s relatively low iron content.

The giant impact hypothesis did not arise from speculation alone. It gained traction because it addressed multiple puzzles simultaneously, offering a unifying explanation where previous theories fell short.

Theia: A Lost World

Theia occupies a unique place in the story of the Moon—a planet-sized body that existed briefly and then vanished, its material scattered and transformed. Though Theia itself has never been observed, its existence is inferred from the need for an impactor of substantial mass.

Theia is thought to have formed in a similar region of the solar system as Earth, perhaps sharing a comparable composition. This proximity is important because it helps explain why lunar rocks resemble Earth’s mantle in many chemical respects. If Theia had originated far from Earth’s orbit, its isotopic signature would likely differ more strongly.

In simulations, Theia typically approaches Earth at a velocity comparable to Earth’s orbital speed, not as a hypervelocity projectile from the outer solar system. The angle of impact is critical. A head-on collision would likely have merged the two bodies completely, while a grazing impact could strip material from both without destroying Earth. The latter scenario is favored because it produces a debris disk rich in silicate material and relatively poor in iron.

The idea that Earth once shared its orbit with another planetary embryo underscores the contingent nature of planetary history. The Earth we know today is not an inevitable outcome but the product of a particular sequence of events, one of which involved the destruction of another world.

The Mechanics of a Planetary Collision

A collision between Earth and Theia would have been an event of unimaginable energy. At the moment of impact, kinetic energy would have been converted into heat, shock waves, and deformation. Portions of both bodies would have melted or vaporized, while other regions would have been flung outward by the force of the collision.

Numerical models suggest that much of the material ejected into orbit came from Earth’s outer layers and from Theia’s mantle. Iron cores, being denser, tended to merge with Earth rather than remain in orbit. This selective process helps explain why the Moon has a much smaller iron core compared to Earth.

The debris disk formed around Earth would have been hot and dynamic. Initially composed of molten and vaporized rock, it would have cooled over time, allowing solid particles to condense and collide. Through gravitational interactions, these particles would gradually accrete into a single dominant body: the Moon.

This process likely occurred relatively quickly on geological timescales, perhaps within a few thousand years. From chaos emerged a stable satellite, locked in orbit around a planet still recovering from trauma.

Evidence from Lunar Rocks

One of the strongest lines of evidence supporting the giant impact hypothesis comes from the analysis of lunar rocks returned by the Apollo missions. These samples revolutionized our understanding of the Moon’s composition and history.

Lunar rocks share remarkable similarities with Earth’s mantle in terms of isotopic ratios of elements such as oxygen. Isotopes act as chemical fingerprints, and matching fingerprints suggest a shared origin or extensive mixing. This similarity was initially surprising, given that the Moon was thought to contain significant material from Theia.

At the same time, lunar rocks show clear differences from Earth in volatile elements. The Moon is depleted in substances that vaporize easily, such as water and certain gases. This depletion is consistent with formation in a high-temperature environment, like the aftermath of a giant impact.

The combination of similarity and difference is key. It suggests that the Moon formed from material that was once part of Earth or intimately mixed with it, but that the formation process involved extreme heating that drove off volatiles. No earlier hypothesis accounted for this pattern as successfully as the giant impact model.

Isotopic Puzzles and Refinements

While isotopic similarities between Earth and Moon support the giant impact hypothesis, they also present challenges. If a significant fraction of lunar material came from Theia, why do Earth and Moon appear so isotopically alike? This question has prompted refinements to the original model.

One possibility is that Theia had a composition very similar to Earth’s because it formed in nearly the same orbital region. Another idea is that the impact led to extensive mixing between Earth’s mantle and the debris disk, homogenizing isotopic differences. High-energy impacts could vaporize rock, allowing isotopes to equilibrate before the Moon fully formed.

More recent models explore variations in impact angle, speed, and mass ratio to reproduce the observed isotopic data. These refinements do not undermine the giant impact hypothesis; rather, they demonstrate its flexibility and its capacity to evolve in response to new evidence.

Science advances through such tension between theory and observation. The isotopic puzzles of the Moon have deepened understanding rather than diminished confidence in the overall framework.

The Moon’s Internal Structure

Seismic data, collected by instruments left on the Moon during the Apollo missions, reveal that the Moon has a differentiated internal structure, including a crust, mantle, and core. However, the lunar core is much smaller relative to the Moon’s size than Earth’s core is relative to Earth.

This structural difference aligns with the giant impact hypothesis. During the collision, iron from both bodies would preferentially sink toward Earth’s core, leaving the debris disk depleted in metal. The Moon, forming from this debris, would naturally have a lower iron content.

The Moon’s mantle and crust also record a history of early melting, consistent with formation from hot material. The concept of a global magma ocean, in which the Moon’s surface was once largely molten, fits well with an origin in impact-generated debris.

These internal features are not incidental details; they are physical records of the Moon’s birth environment. The Moon’s very structure is a geological memory of catastrophe.

Angular Momentum and Orbital Dynamics

Any theory of the Moon’s origin must account for the angular momentum of the Earth–Moon system. Angular momentum describes how mass and motion are distributed in a rotating system, and it is conserved in isolated systems.

The Earth–Moon system has a large amount of angular momentum, reflected in Earth’s rotation and the Moon’s orbital motion. The giant impact hypothesis naturally explains this by transferring angular momentum from the collision into the newly formed system.

Simulations show that certain impact scenarios produce angular momentum values close to those observed today. Over time, tidal interactions between Earth and Moon have modified the system, slowing Earth’s rotation and causing the Moon to gradually recede. These long-term processes build upon the initial conditions set by the impact.

The ability of the giant impact hypothesis to reproduce not only the Moon’s composition but also its orbital characteristics is a major reason for its acceptance within the scientific community.

The Moon’s Influence on Earth

Understanding the Moon’s origin also sheds light on its profound influence on Earth. The Moon stabilizes Earth’s axial tilt, reducing extreme variations in climate over geological timescales. It drives ocean tides, which may have played a role in the development of early life. It also slows Earth’s rotation through tidal friction, lengthening days over billions of years.

These effects are consequences of the Moon’s mass, orbit, and proximity—properties shaped by its formation. Had the impact been different, Earth might have ended up with no large moon or with multiple smaller satellites. Such alternative outcomes could have led to a very different planetary environment.

In this sense, the giant impact hypothesis connects the Moon’s violent birth to the conditions that later allowed life to flourish on Earth. Catastrophe and creation are intertwined.

Competing and Alternative Models

Although the giant impact hypothesis is the leading explanation, it is not the only model explored by scientists. Alternative scenarios, such as multiple smaller impacts or variations in impact dynamics, have been proposed to address specific issues like isotopic similarity.

Some models suggest that the Moon formed from a series of collisions rather than a single event, with debris gradually accumulating. Others explore the possibility of a more massive impact that led to extensive mixing. These ideas are best viewed not as rivals but as extensions of the core concept that impact-driven processes shaped the Earth–Moon system.

The willingness of scientists to explore alternatives reflects the strength, not weakness, of planetary science. By testing variations, researchers refine their understanding and identify which aspects of the model are essential and which are flexible.

The Role of Computer Simulations

The giant impact hypothesis owes much of its development to advances in computational physics. Simulating a planetary collision requires modeling gravity, fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and material behavior under extreme conditions. Such simulations are computationally demanding, but they allow scientists to explore scenarios that cannot be recreated experimentally.

As computational power has increased, simulations have become more detailed and realistic. They now incorporate complex equations of state for rock and metal, track vaporization and condensation, and follow the long-term evolution of debris disks.

These models do more than illustrate ideas; they generate quantitative predictions that can be compared with observations. In this way, computer simulations serve as a bridge between theory and evidence, transforming speculative narratives into testable science.

What the Moon Tells Us About Planet Formation

The story of the Moon’s origin extends beyond Earth. Giant impacts are now recognized as a common feature of planet formation throughout the universe. Observations of exoplanetary systems and debris disks around young stars support the idea that collisions shape planetary architectures.

By studying the Moon, scientists gain insight into processes that likely occurred on other terrestrial planets, including Mars and Venus. The absence of a large moon around Venus, for example, raises questions about its collisional history and its subsequent evolution.

The Moon thus serves as a natural laboratory for understanding how planets grow, differentiate, and interact. Its origin story is a case study with implications that reach far beyond our own world.

Emotional Resonance of a Violent Birth

There is a profound emotional dimension to the giant impact hypothesis. The Moon, often associated with calmness and romance, emerges from this narrative as a survivor of cosmic violence. Its existence is a reminder that beauty can arise from destruction, that stability can follow chaos.

For many, this realization deepens rather than diminishes the Moon’s significance. The Moon becomes not only a symbol but a testament to resilience, a scar left by an ancient wound that healed into something enduring and life-shaping.

Science does not strip the universe of meaning; it adds layers to it. Knowing that the Moon formed from the remnants of a lost world invites reflection on impermanence, chance, and the interconnectedness of cosmic events.

Remaining Questions and Future Research

Despite the success of the giant impact hypothesis, questions remain. The precise nature of Theia, the exact conditions of the impact, and the details of isotopic equilibration continue to be areas of active research. Future lunar missions, including sample returns from previously unexplored regions, may provide new clues.

Advances in analytical techniques allow scientists to measure isotopic ratios with increasing precision, revealing subtle differences that could refine models further. Improved simulations will continue to test the limits of impact scenarios.

Science thrives on such open questions. The Moon’s origin is not a closed case but an evolving story, one that grows richer as new evidence emerges.

Conclusion: A Moon Born of Fire and Chance

The hypothesis that the Moon formed from a collision with Theia represents one of the most powerful ideas in planetary science. It explains the Moon’s composition, structure, and orbit through a single, transformative event. It situates Earth’s history within a broader cosmic context of collision and creation.

The Moon we see today is the quiet aftermath of an ancient catastrophe, a companion forged in fire and motion. Its existence reminds us that the universe is dynamic, shaped by both violence and order. To look at the Moon with this knowledge is to see not just a celestial body, but a chapter of Earth’s autobiography written in rock and light.

In understanding the Moon’s origin, we come closer to understanding ourselves—not only as inhabitants of Earth, but as participants in a vast, unfolding cosmic story where chance encounters can give rise to enduring worlds.