Each night, when we close our eyes and surrender to sleep, we cross a threshold into a world that is at once familiar and alien. In dreams, the boundaries of time and space dissolve. The living embrace the dead, impossible landscapes unfold with ease, and the deepest desires or fears take vivid form. We wake, sometimes with a smile, sometimes in terror, sometimes in confusion. And in that fragile moment between dream and waking, we often ask the oldest question in human history: Why do we dream?

Dreams have always been part of us. Long before there were laboratories, EEG machines, or neuroscientists, our ancestors gazed into the firelight and shared tales of dreams. They believed them to be messages from gods, glimpses into the future, or journeys of the soul leaving the body. Even now, in the 21st century, after centuries of science, dreams remain among the greatest mysteries of the mind.

Ancient Visions of the Dream World

To understand why dreams fascinate us, we must first look at how humans across history have understood them. In Mesopotamia, dream tablets inscribed in cuneiform over 4,000 years ago show that people believed dreams carried divine messages. Egyptian priests acted as interpreters of dreams, decoding them as signs of health, destiny, or warnings from the gods.

The Greeks brought philosophy into the realm of dreams. Aristotle wrote about them as natural phenomena—echoes of the day’s experiences. Plato, meanwhile, suggested that dreams revealed the hidden desires of the soul. Hippocrates believed dreams could diagnose illness, seeing them as a mirror of the body’s internal state.

In the Bible, dreams shape destinies—Joseph interprets Pharaoh’s dreams of famine, guiding the survival of Egypt. In Islam, the Prophet Muhammad described dreams as one of the forty-six parts of prophecy. In cultures from the Aboriginal Australians to the Mayans, dreams were not illusions but alternate realities—another layer of existence as real as waking life.

Even today, remnants of these beliefs linger. We speak of “dream interpretation,” of symbols and omens, of good dreams and bad dreams. Though science has pushed us forward, the human heart still feels that dreams must mean something.

The Science of Sleeping and Dreaming

Modern neuroscience has made extraordinary progress in uncovering the biological foundations of dreaming. Sleep is not a passive state of rest, but a dynamic process with distinct stages.

When we first drift into sleep, our brain activity slows. This is non-REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep, which has multiple phases, from light drowsiness to deep, restorative slumber. But then, roughly every 90 minutes, our brain enters a vivid state: REM sleep.

In REM sleep, the brain becomes highly active, almost as if awake. The eyes dart rapidly beneath closed lids. Heart rate and breathing fluctuate. It is during this stage that the most intense and memorable dreams occur. EEG studies show bursts of electrical activity in regions involved in emotion, memory, and imagination, while the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for logic and self-control—remains subdued. This combination explains why dreams feel emotionally intense, surreal, and free of the constraints of rationality.

Yet dreams are not limited to REM. Non-REM dreams exist as well, often less vivid but equally meaningful. Sleep, in essence, provides multiple theaters for the mind to play its nightly dramas.

But here lies the great puzzle: Why does the brain dream at all? After all, dreaming consumes enormous amounts of energy. Evolution rarely wastes resources. So dreams must serve a purpose—or perhaps many purposes.

Dreams as Memory Weavers

One of the most compelling scientific theories suggests that dreams help us consolidate memory. When we are awake, experiences flood the brain, filling the hippocampus with information. During sleep—especially during REM—the brain replays and reorganizes these memories, transferring them into long-term storage.

Dreams, in this view, are the emotional “echoes” of this process. That is why students often dream of exams, or why new parents dream of their crying infant. The brain is sorting, prioritizing, and linking experiences into a coherent narrative. Studies show that people deprived of REM sleep struggle with memory, learning, and problem-solving. Dreams may be the brain’s way of making sense of chaos, stitching together fragments of life into a larger pattern.

This explains why dreams often feel bizarre. Our brains are not recreating experiences perfectly but remixing them, drawing associations between seemingly unrelated ideas. That strange dream where your childhood home merges with your workplace? It may be the brain linking past memories with present challenges, searching for meaning in the web of experience.

Dreams as Emotional Healers

Another powerful theory views dreams as a form of emotional therapy. In waking life, emotions can overwhelm us—grief, fear, anger, love. When we dream, the brain reactivates these emotions but in a safe, virtual environment. The amygdala, the brain’s fear center, lights up during REM sleep, while stress chemicals like norepinephrine drop. This means we can confront emotionally charged material without full biological stress.

Dreams, then, may act like a nightly rehearsal. We revisit painful experiences, process them, and emerge with greater emotional balance. Research supports this: people who dream about traumatic events often show reduced anxiety about them afterward. Soldiers with PTSD, however, sometimes become trapped in terrifying nightmares, unable to heal. In such cases, the dream’s function is disrupted, turning therapy into torment.

But in healthy dreaming, our nights may serve as therapy sessions led by the unconscious mind itself. Perhaps this is why heartbreak feels less raw after weeks of strange, bittersweet dreams. Perhaps this is why grief, though never erased, becomes gentler with time. Our dreams carry some of that burden for us.

Dreams as Creative Sparks

Dreams are also a forge of creativity. Freed from the rigid rules of waking logic, the dreaming brain generates new connections. Artists, writers, and scientists throughout history have credited dreams with breakthroughs.

Mary Shelley dreamt of a corpse reanimated by electricity—a vision that became Frankenstein. Paul McCartney awoke with the melody of Yesterday fully formed in his mind. The chemist Friedrich August Kekulé claimed that the structure of the benzene molecule came to him in a dream of a snake biting its tail.

Even Einstein was influenced by dreamlike thought experiments, imagining himself chasing beams of light. While not literal dreams, his insights carried the fluid, surreal quality of dream imagery.

Modern studies support this link. REM sleep enhances problem-solving and creativity. By loosening the strict boundaries of logic, dreams allow the mind to explore possibilities we might never consider while awake. In this way, our dreams may be the silent partner in humanity’s greatest inventions.

The Dark Side of Dreams

Of course, not all dreams comfort or inspire. Nightmares are among the most haunting experiences humans endure. They jolt us awake in sweat, heart pounding, as if death itself has brushed against us. Why would evolution burden us with such terror?

Some scientists argue that nightmares serve a survival function. By simulating threatening situations—being chased, attacked, falling—the brain rehearses danger, preparing us for real-world threats. This aligns with the “threat simulation theory” proposed by Finnish psychologist Antti Revonsuo. In ancestral times, those who dreamt of predators may have been better prepared to respond when danger appeared in waking life.

But nightmares also reflect the mind’s deepest anxieties. They may surface during times of stress, trauma, or illness. For some, they become chronic, as in PTSD, disrupting rather than aiding survival. Here, the ancient survival function becomes maladaptive, trapping the dreamer in cycles of fear.

Yet even nightmares remind us that dreams are not random noise. They speak the language of our fears, carrying messages we may not wish to hear but cannot ignore.

Freud, Jung, and the Language of the Unconscious

No discussion of dreams can ignore the profound influence of psychology. In 1899, Sigmund Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, declaring dreams the “royal road to the unconscious.” Freud believed that dreams were disguised expressions of repressed desires, often sexual. He saw dream symbols—like houses, animals, or journeys—as veiled expressions of hidden wishes.

Though many of Freud’s specific ideas have been challenged or dismissed, his central insight—that dreams reveal the unconscious—remains influential. He understood that dreams are not meaningless but charged with emotional truth, even if hidden beneath layers of symbolism.

Carl Jung, Freud’s student turned rival, expanded the theory. He saw dreams not merely as personal wish-fulfillment but as messages from the deeper collective unconscious. Jung believed archetypal figures—the wise old man, the shadow, the mother—appeared in dreams as universal symbols of human experience. For Jung, dreams were guidance from the psyche, urging personal growth and integration.

Though modern neuroscience has shifted away from pure psychoanalysis, the cultural and symbolic interpretations of dreams continue to resonate. Even if we no longer believe every dream conceals repressed desire, we still feel that dreams carry meaning, that they are woven from the fabric of our lives.

Do Dreams Tell the Future?

One of the most persistent beliefs across history is that dreams can foretell the future. From Pharaoh’s prophetic dreams in the Bible to countless cultural traditions, people have sought omens in the dream world. Science remains skeptical. Controlled studies have found no evidence that dreams literally predict events.

Yet dreams often feel prophetic because of how the mind works. Dreams weave together fragments of our daily lives, including subtle details we may not consciously notice. For example, if you dream of a friend calling you, and the next day that friend reaches out, it may feel supernatural. But perhaps your unconscious picked up cues—your friend’s recent mood, a passing memory—that made the dream more likely.

Dreams can also reflect the trajectory of our emotions and decisions. A person dreaming of leaving their job may not be predicting the future, but revealing an unconscious truth: dissatisfaction already stirring within them. In this sense, dreams do not tell the future but reveal the seeds of it planted in the present.

The Brain’s Theater of the Self

Perhaps the most profound aspect of dreaming is what it reveals about the self. In waking life, we often wear masks. We perform roles, suppress emotions, and bend to social expectation. But in dreams, the unconscious stages its own theater. We meet forgotten loved ones, confront enemies, embrace impossible versions of ourselves.

Neuroscience suggests that dreams are the brain’s way of integrating the many layers of identity—memories, desires, fears, and imagination. They are a nightly rehearsal of selfhood, a laboratory of being. That is why dreams feel so intensely personal. No one else can dream your dream. It is the purest expression of you, unfiltered by the waking world.

This also explains why dreams are so difficult to explain to others. Language struggles to capture their essence. A dream feels profound, but when told, it slips into absurdity. Dreams resist translation because they are written in the unique code of the dreamer’s psyche.

What Dreams Mean in the End

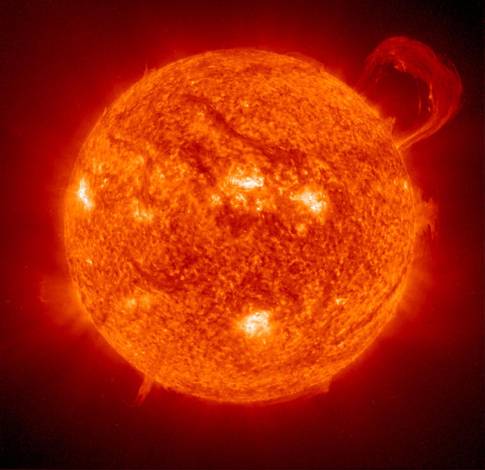

So, why do we dream? The answer is layered, like the dreams themselves. We dream because our brains must process memory, regulate emotion, and fuel creativity. We dream because evolution shaped us to rehearse threats, to prepare for survival. We dream because the unconscious has truths to tell that waking life cannot contain.

And what do dreams mean? They mean what we make of them. Science can tell us about neurons firing, about REM cycles and amygdala activity. But the meaning of a dream lives in the dreamer. A dream of flying might be, neurologically, a burst of visual cortex activity. But to the dreamer, it might mean freedom, ambition, or escape.

Dreams matter because we experience them as meaningful. They are the poetry of the mind, written each night in the language of images. Even when bizarre, even when terrifying, they remind us that beneath logic and routine, we are creatures of mystery.

The Endless Dream

Every night, humanity closes its eyes and travels into hidden worlds. Across cultures, across centuries, across the vast differences of life, we all dream. It is the universal bridge between biology and imagination.

Perhaps dreams do not come from outside us—no gods whispering, no spirits visiting—but from the depths within us. Yet that does not make them less miraculous. For inside the fragile cage of the human skull lies a cosmos as vast and strange as the stars. Dreams are the nightly proof that we carry infinity inside us.

And when we ask why we dream, we are really asking something larger: What is the mind? What is consciousness? What is it to be human? Dreams are not the answer, but they are part of the question. And maybe that is enough.