Deep beneath our feet, far beyond the deepest mines and the hottest volcanic chambers, lies a realm no human has ever seen directly. It is a world of crushing pressure, searing heat, and metallic motion—a hidden engine that has been running for billions of years. This is Earth’s core, often called the planet’s iron heart. Though inaccessible, it plays a decisive role in shaping the surface world we inhabit. The magnetic field that shields life from cosmic radiation, the slow drift of continents, and even the long-term stability of Earth’s climate are all connected, directly or indirectly, to the restless heat deep inside the planet.

To imagine Earth without its hot, dynamic core is to imagine a profoundly different world. The question “What would happen if Earth’s core cooled down?” is not merely a speculative exercise. It is a scientifically meaningful inquiry that reveals how delicately balanced Earth’s internal systems are, and how deeply our survival depends on processes unfolding thousands of kilometers below the surface. Cooling is not an abstract idea here; it is something that is already happening, albeit extremely slowly. Earth is losing heat, just as all warm objects in the universe eventually do. The real question is what that cooling means, and how far it could go.

A Journey to the Center of the Earth

Earth’s interior is structured in layers, defined by both composition and physical state. Beneath the thin crust lies the mantle, a vast region of hot, solid rock that behaves plastically over geological time. Below the mantle sits the core, which is divided into two parts: a liquid outer core and a solid inner core. Both are composed primarily of iron, with smaller amounts of nickel and lighter elements.

The outer core, extending from about 2,900 kilometers below the surface to around 5,150 kilometers, is molten. Temperatures here range from roughly 4,000 to over 5,000 degrees Celsius, hot enough to melt iron despite the immense pressure. Beneath it lies the inner core, a solid sphere about the size of the Moon. The inner core is even hotter, but the pressure is so extreme that iron remains solid despite the intense heat.

This structure is not static. Heat flows outward from the core into the mantle, and this heat flow drives many of Earth’s large-scale processes. The gradual cooling of the planet over billions of years has shaped its evolution, and the current state of the core represents a balance between residual heat from Earth’s formation, heat released by radioactive decay, and the slow loss of energy into space.

Why the Core Is Hot in the First Place

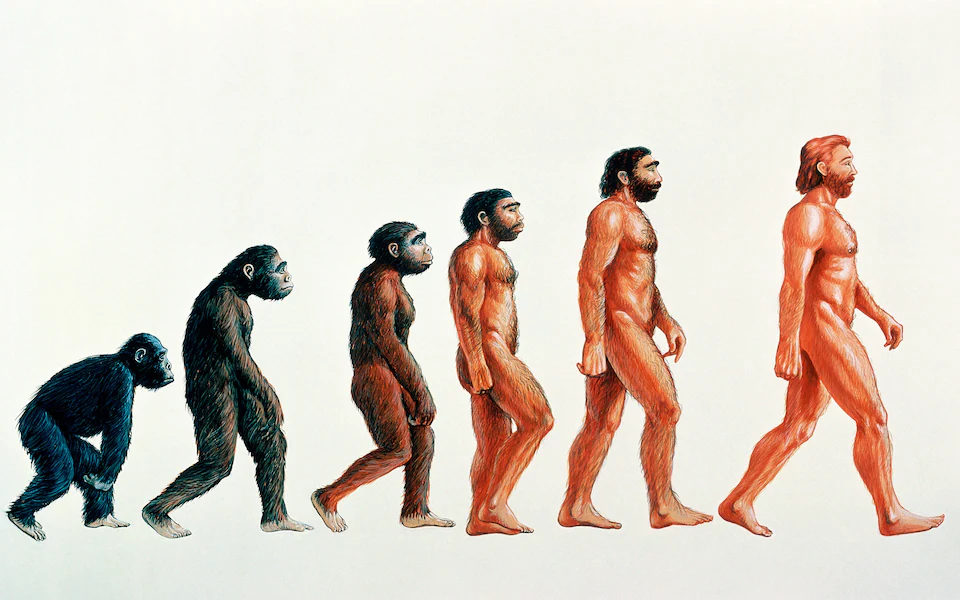

To understand what would happen if Earth’s core cooled down, it is essential to understand why it is hot at all. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of dust and rock in the early solar system. As material accumulated, gravitational energy was converted into heat, raising the planet’s temperature. Heavy elements such as iron sank toward the center, releasing additional heat through a process known as gravitational differentiation.

Radioactive elements within Earth also contribute to its internal heat. The decay of isotopes such as uranium, thorium, and potassium produces energy that warms the surrounding rock. While most radioactive heating occurs in the mantle and crust, it indirectly affects the core by influencing the overall thermal balance of the planet.

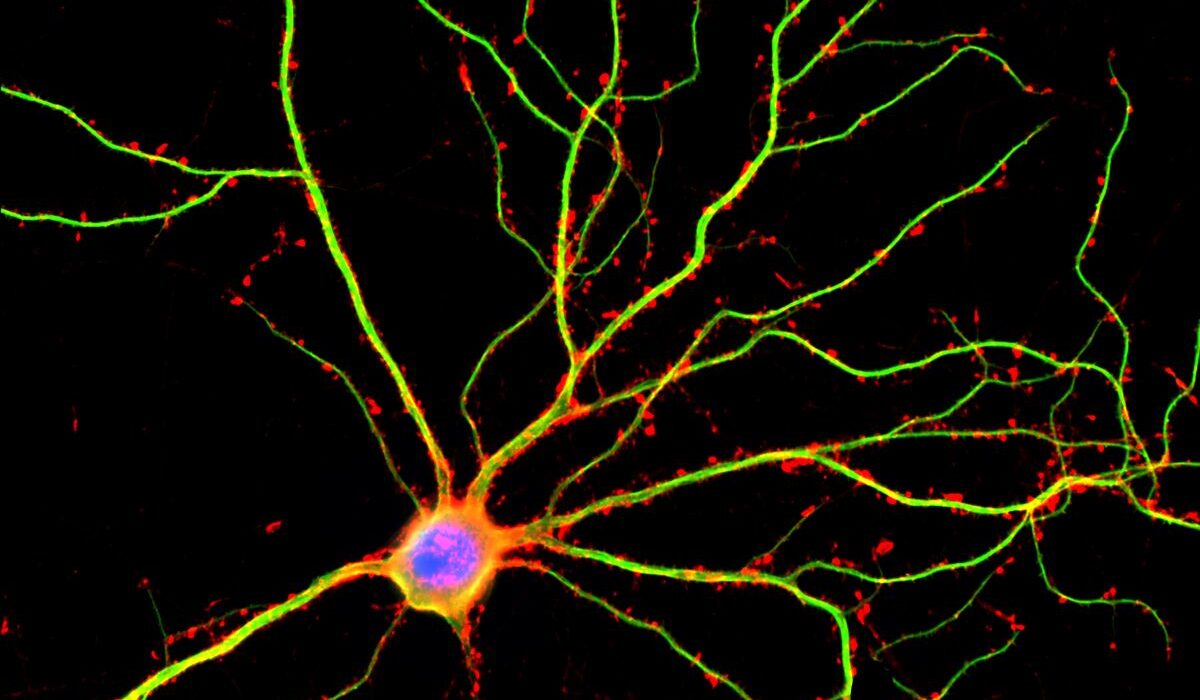

Another crucial source of heat comes from the growth of the inner core. As the inner core slowly solidifies from the liquid outer core, it releases latent heat of crystallization and expels lighter elements into the outer core. Both processes help maintain convection in the liquid iron surrounding the inner core. This convective motion is central to one of the core’s most vital functions: generating Earth’s magnetic field.

The Magnetic Field: Earth’s Invisible Shield

One of the most dramatic consequences of a cooling core would involve Earth’s magnetic field. This field is generated by the geodynamo, a process driven by the motion of electrically conductive liquid iron in the outer core. As the molten metal circulates due to heat and compositional differences, it creates electric currents, which in turn produce a magnetic field.

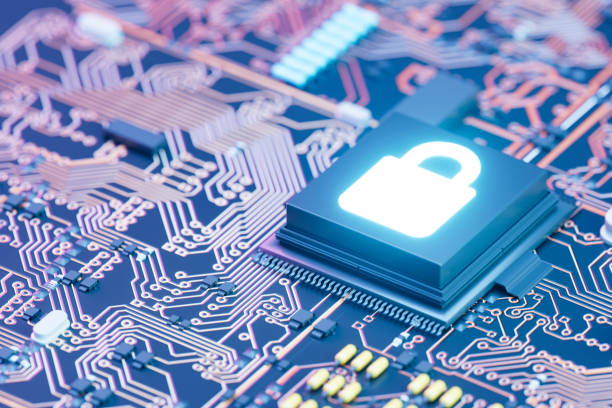

The magnetic field extends far into space, forming the magnetosphere, which deflects charged particles from the Sun and cosmic radiation from beyond the solar system. Without this shield, Earth’s atmosphere would be far more vulnerable to erosion by solar wind, and the surface would be exposed to higher levels of harmful radiation.

If the core cooled significantly, the temperature difference driving convection in the outer core would diminish. As convection slowed, the geodynamo would weaken. A sufficiently cooled core could eventually halt the dynamo altogether, leading to the collapse of the global magnetic field. Earth would not instantly lose all magnetic influence, but the organized, dipole-dominated field we rely on would fade, possibly leaving behind only weak, localized magnetic remnants.

Lessons from Other Worlds

The solar system provides powerful examples of what happens to planets whose cores cool and lose dynamo action. Mars is a particularly instructive case. Geological evidence suggests that Mars once had a global magnetic field generated by a molten core. Over time, Mars cooled more rapidly than Earth due to its smaller size. As its core lost heat, convection weakened and the dynamo shut down.

The loss of Mars’s magnetic field exposed its atmosphere to solar wind stripping. Over hundreds of millions of years, much of the atmosphere was eroded away, contributing to the cold, dry conditions observed today. While Earth is larger and retains heat more effectively, Mars offers a cautionary glimpse of a future that could unfold if Earth’s core were to cool dramatically.

Mercury provides another perspective. Despite its small size, Mercury still has a weak magnetic field, suggesting that at least part of its core remains molten. This challenges simple assumptions about cooling rates and highlights how composition and internal structure can influence a planet’s thermal evolution. Even so, Mercury’s magnetic field is far weaker than Earth’s, underscoring the importance of sustained core heat for a strong dynamo.

The Slow Dance of Cooling

Earth’s core is cooling, but on timescales that dwarf human history. Heat flows outward at a rate of roughly tens of terawatts, an enormous amount by everyday standards but modest compared to the planet’s total thermal energy. Estimates suggest that the inner core began solidifying about one billion years ago, and it continues to grow slowly as the planet cools.

This gradual cooling is not a catastrophe; it is part of Earth’s long-term evolution. In fact, the growth of the inner core currently helps sustain the geodynamo by releasing heat and driving compositional convection. Paradoxically, some cooling is necessary to keep the magnetic field alive. The danger lies not in cooling itself, but in cooling too far, when the outer core can no longer sustain vigorous motion.

From a human perspective, this process is almost imperceptible. Even if the geodynamo were to fail in the distant future, it would do so over millions of years, not overnight. Nevertheless, understanding this slow dance of thermal evolution is essential for grasping Earth’s ultimate fate.

A World Without a Strong Magnetic Field

If Earth’s magnetic field weakened significantly or disappeared, the effects would ripple outward through the planet’s systems. One of the most immediate consequences would be increased exposure to charged particles from the Sun. Solar storms would have a more direct impact on the upper atmosphere, potentially enhancing atmospheric loss over geological time.

Life on Earth would not vanish instantly, but the environmental stresses would be substantial. Increased radiation at the surface could raise mutation rates and disrupt ecosystems, particularly at high altitudes and near the poles. Technological civilization would be especially vulnerable, as satellites, power grids, and communication systems depend on the stability provided by Earth’s magnetic shield.

The atmosphere itself would gradually change. While Earth’s gravity is strong enough to retain most of its atmosphere even without a magnetic field, the rate of atmospheric escape would likely increase. Over hundreds of millions to billions of years, this could alter atmospheric composition and pressure, with profound implications for climate and habitability.

The Core and Plate Tectonics

Beyond the magnetic field, the cooling of Earth’s core would also influence plate tectonics, though the connection is more indirect. Plate tectonics is driven primarily by convection in the mantle, which in turn depends on heat flowing from the core and radioactive decay within the mantle itself.

If the core cooled significantly, the heat flux into the mantle would decrease. Over long timescales, this could weaken mantle convection, slowing the movement of tectonic plates. Mountain building, earthquakes, and volcanic activity would become less frequent. The surface of the planet would gradually become more geologically static.

This process can be seen on the Moon, which has been tectonically inactive for billions of years. Without sufficient internal heat, the Moon’s mantle convection ceased, freezing its surface into a largely unchanging state. Earth, by contrast, owes much of its geological dynamism to its still-warm interior.

Climate Consequences of a Cooling Interior

The connection between Earth’s core and climate is subtle but real. Volcanic activity, driven by mantle heat, plays a role in regulating atmospheric composition by releasing gases such as carbon dioxide and water vapor. Over geological timescales, this volcanic outgassing helps balance processes that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, such as weathering and sedimentation.

If core cooling led to a significant reduction in volcanic activity, the long-term carbon cycle could be disrupted. Reduced outgassing would eventually lower atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, potentially leading to global cooling. While such changes would unfold over millions of years, they could push the planet toward a colder, less hospitable climate state.

Earth’s history includes episodes, such as “snowball Earth” events, when global temperatures dropped dramatically. While these were not caused by core cooling alone, they illustrate how sensitive climate can be to changes in internal and surface processes. A colder interior would tilt the balance toward reduced geological and atmospheric activity.

The Inner Core’s Silent Growth

One of the most fascinating aspects of Earth’s core is that cooling does not simply mean becoming inert. As the planet loses heat, the inner core continues to grow, slowly crystallizing from the liquid outer core. This growth is a dynamic process that influences seismic behavior, core composition, and the geodynamo itself.

Seismic studies reveal that the inner core is not perfectly uniform. It appears to have complex structures and possibly anisotropic properties, meaning that seismic waves travel through it differently in different directions. These features may reflect variations in crystal alignment, temperature, or composition, offering clues to the core’s thermal history.

If cooling progressed far enough, the entire core could eventually solidify. At that point, the geodynamo would almost certainly cease, as solid iron cannot sustain the convective motions required to generate a global magnetic field. Earth would enter a new phase of its planetary life, fundamentally different from the one that has supported life for billions of years.

Timescales Beyond Human Imagination

It is important to emphasize that a fully cooled core is not a near-term concern. Estimates suggest that Earth’s core will remain at least partially molten for billions of years. By the time the geodynamo finally shuts down, the Sun itself will be entering a different phase of its evolution, likely rendering Earth uninhabitable for other reasons.

Nevertheless, thinking about core cooling stretches our imagination and situates humanity within deep time. It reminds us that Earth is not a static stage on which life plays out, but an evolving system with a finite thermal lifespan. The conditions that make our planet hospitable are temporary on cosmic timescales, even if they feel permanent within a human lifetime.

This perspective can evoke both humility and wonder. We are beneficiaries of a particular moment in Earth’s long history, living at a time when the iron heart still beats vigorously beneath our feet.

Could Core Cooling Be Accelerated?

In scientific terms, Earth’s core cooling is governed by fundamental physical processes that are largely beyond external influence. Human activity, no matter how technologically advanced, cannot meaningfully alter the heat flow from the core. The energy scales involved are simply too vast.

However, understanding core cooling has practical implications for interpreting geophysical data and assessing planetary habitability elsewhere. When scientists study exoplanets, one key question is whether those worlds have active dynamos and magnetic fields. The presence or absence of a molten core can influence a planet’s ability to support life, at least life as we know it.

Thus, Earth’s core serves as a reference point, a natural laboratory for understanding how rocky planets evolve and how long they can remain habitable.

Emotional Resonance of a Cooling World

There is something deeply evocative about imagining Earth’s iron heart slowly losing its heat. The idea carries a quiet melancholy, a sense of impermanence that contrasts sharply with the apparent solidity of the ground beneath our feet. Mountains seem eternal, continents immovable, yet beneath them lies a dynamic system that will one day fall silent.

At the same time, there is beauty in this inevitability. The cooling of the core is not a failure but a natural consequence of physical laws. It is part of the same cosmic story that governs the lives of stars, the formation of planets, and the eventual fate of the universe itself.

By understanding this story, we deepen our connection to the planet we call home. Knowledge does not diminish wonder; it enhances it, revealing layers of meaning beneath the surface of everyday experience.

Earth Compared to a Living Organism

The metaphor of Earth as a living organism is not scientifically literal, but it is emotionally powerful. The core, in this analogy, functions like a heart, driving circulation and sustaining vital processes. When the heart weakens, the organism changes profoundly.

Earth’s “heartbeat” is measured not in seconds but in millions of years, yet the analogy helps convey the interdependence of planetary systems. The magnetic field, tectonics, atmosphere, and biosphere are all connected, directly or indirectly, to the heat deep within the planet.

Recognizing these connections fosters a sense of planetary stewardship. While we cannot control Earth’s internal evolution, we can choose how we interact with the surface systems that depend on it. Understanding physics and geology becomes a way of grounding ethical responsibility in scientific reality.

The Distant Future of Earth

If we project far into the future, beyond the span of human civilization, Earth will eventually become a colder, quieter world. Volcanism will wane, plate tectonics may cease, and the magnetic field could fade away. The planet will resemble, in some respects, the geologically inactive worlds we see elsewhere in the solar system.

By that time, the Sun’s increasing luminosity will likely have already transformed Earth’s surface, evaporating oceans and rendering the planet uninhabitable long before the core fully solidifies. In this sense, core cooling is only one thread in a complex tapestry of planetary change.

Yet contemplating this distant future highlights the extraordinary stability Earth has enjoyed for billions of years. The persistence of a molten core, a protective magnetic field, and active geology has allowed life not only to arise but to flourish and diversify in remarkable ways.

Why This Knowledge Matters Now

Understanding what would happen if Earth’s core cooled down is not about predicting an imminent disaster. It is about appreciating the deep physical processes that sustain our world. This knowledge enriches our understanding of Earth as a system and sharpens our ability to interpret data from other planets.

It also serves as a reminder of how rare and precious Earth-like conditions may be. A planet’s internal heat budget, magnetic field, and geological activity are not guaranteed features; they are contingent outcomes of formation history and physical laws.

In a broader sense, studying Earth’s core reinforces the value of basic science. Much of what we know about the core comes from indirect evidence, such as seismic waves and magnetic measurements, interpreted through physics. These insights are the result of curiosity-driven research that, at first glance, might seem abstract but ultimately deepens humanity’s understanding of its place in the universe.

Conclusion: Listening to the Silent Engine

Earth’s core is silent to our ears, hidden from our eyes, yet it speaks through magnetic fields, seismic waves, and the slow movement of continents. To ask what would happen if it cooled down is to listen carefully to that silent engine and to recognize its central role in shaping the planet’s past, present, and future.

The iron heart beneath our feet is not eternal. One day, far beyond the horizon of human time, it will cool and still. When that happens, Earth will become a different world. Until then, its warmth sustains a delicate balance that allows oceans to shimmer, compasses to point north, and life to thrive under a protective magnetic sky.

In understanding this hidden heart, we do more than learn about geology or physics. We gain perspective on impermanence, interconnectedness, and the extraordinary good fortune of living on a planet whose inner fire still burns.