In the soft light of the Greek sun, where olive groves spread across rugged hills and the Aegean Sea whispers against the shores, lies a story buried beneath the earth for more than three thousand years. It is a story of kings and warriors, of death and remembrance, of dazzling gold hammered into the likeness of human faces. These are the gold masks of Mycenaean Greece—artifacts that gleam not only with the brilliance of their material but also with the echoes of a civilization whose grandeur helped shape the course of history.

To encounter one of these masks is to feel the weight of time pressing in. The thin sheets of gold, molded into serene and solemn visages, speak across millennia with a quiet power. They are both intimate and otherworldly, representations of individuals who once lived, loved, fought, and died, but also symbols of status, ritual, and belief. The gold masks of Mycenae are among the most striking treasures of the ancient world, bridging the human need to honor the dead with the artistry of one of Europe’s earliest great civilizations.

Mycenaean Greece: The Age of Heroes

The story of the masks begins with the Mycenaeans, a people who flourished in mainland Greece during the Late Bronze Age, roughly from 1600 to 1100 BCE. They inherited and transformed the traditions of earlier Aegean cultures, such as the Minoans of Crete, and laid the foundations for what later Greeks would remember as the heroic age—the age immortalized in Homer’s epics.

Mycenae itself, perched on a rocky outcrop in the Peloponnese, was one of the most powerful centers of this civilization. With its massive stone walls, monumental gates, and royal tombs, Mycenae inspired awe even in antiquity. To later Greeks, it was the city of Agamemnon, the legendary commander of the Trojan War. To modern archaeology, it is the site where Heinrich Schliemann, the German adventurer-turned-archaeologist, unearthed the gold masks in the late 19th century, believing he had found the face of Agamemnon himself.

The Mycenaeans were warriors and rulers, merchants and artisans, seafarers and statesmen. They built palatial complexes, wielded influence across the Mediterranean, and developed a script known as Linear B, the earliest form of written Greek. Yet they were also a society deeply concerned with death and the afterlife, as shown by their monumental tombs and lavish grave goods. It is within this context that the gold masks take on their full meaning.

Discovery and the Face of Agamemnon

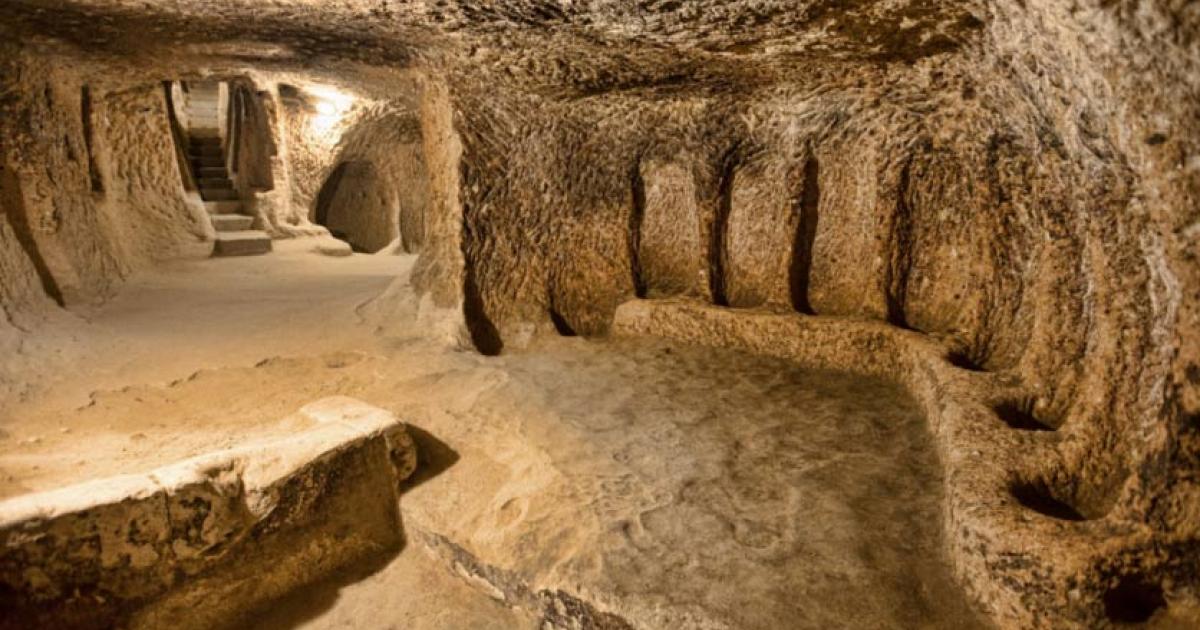

In 1876, Heinrich Schliemann arrived at Mycenae, driven by a singular passion: to prove that Homer’s epics were not mere myths but rooted in historical truth. Digging within the area known as Grave Circle A, he uncovered shaft graves filled with astonishing treasures—bronze weapons, jewelry, pottery, and, most strikingly, several gold masks placed over the faces of the deceased.

One mask, with a finely detailed beard, mustache, and carefully rendered features, captivated Schliemann’s imagination. Declaring it to be the face of Agamemnon, the commander of the Greeks at Troy, he announced to the world that he had gazed upon the visage of a Homeric hero. His words, whether or not they were accurate, ignited public fascination and established the gold masks of Mycenae as iconic symbols of the Bronze Age.

Today, scholars know that the mask predates the legendary Trojan War by several centuries, making it unlikely to be Agamemnon’s. Still, the romantic misidentification lingers in popular culture. Beyond the myths, the masks themselves remain remarkable archaeological finds, windows into the artistry, beliefs, and social structures of Mycenaean Greece.

Craftsmanship in Gold

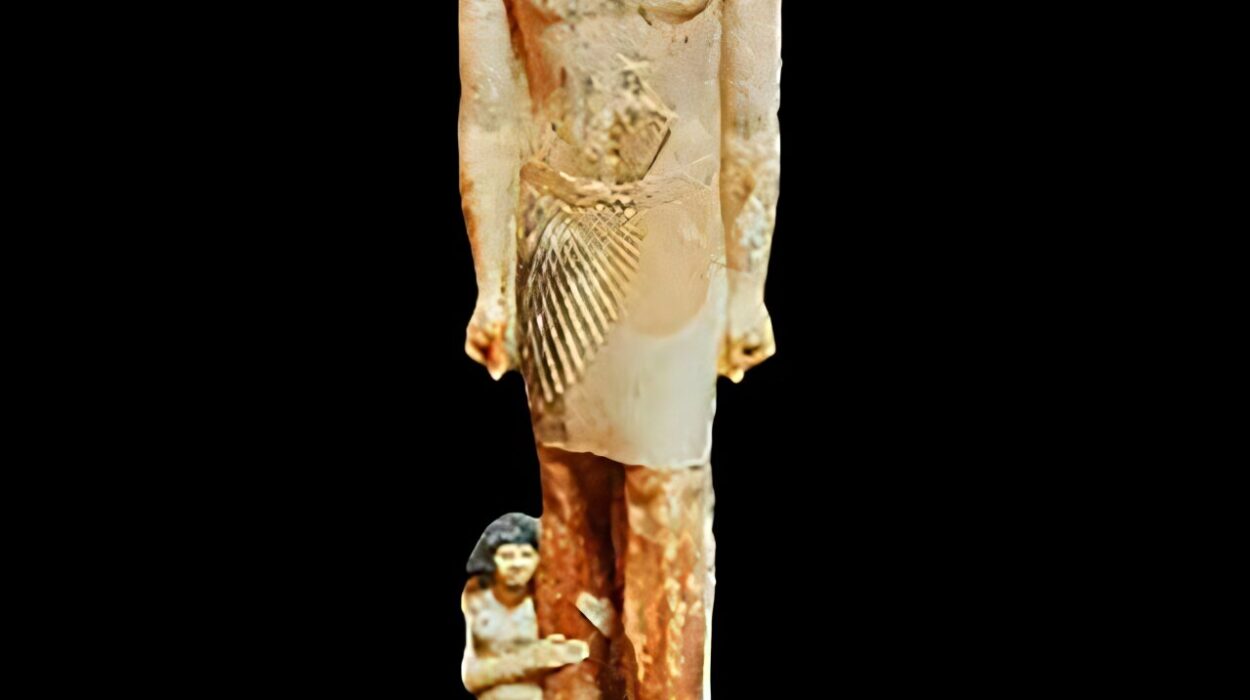

The gold masks of Mycenae are breathtaking not only for their material but for the craftsmanship they reveal. Created from thin sheets of hammered gold, they were shaped using a technique called repoussé, in which artisans carefully worked the metal from the reverse side to raise features in relief. With only simple tools, Mycenaean goldsmiths captured the contours of the human face—eyes, noses, mouths, ears, even subtle details like mustaches or wrinkles.

Each mask is unique. Some show youthful smoothness, while others depict older faces, perhaps indicating attempts to represent specific individuals. Others appear more stylized, with geometric or idealized features that suggest symbolic meaning rather than portraiture. The artistry reflects both technical skill and cultural values: gold was not only a material of beauty and wealth but also a medium of immortality, resistant to decay.

The masks were not meant to be worn in life. They were funerary objects, laid gently over the faces of the deceased, affixed perhaps with ties or adhesive substances. In doing so, they created an eternal visage for the dead, preserving their identity in the glittering permanence of gold.

The Meaning of the Masks

Why did the Mycenaeans craft and use these golden masks? The answer lies in their beliefs about death, memory, and social status. To cover the face of the deceased with gold was to honor them, to shield their identity, and perhaps to prepare them for an afterlife. In many cultures, the face is the essence of individuality—the mask ensured that individuality was preserved, even in death.

The use of gold, a metal that does not tarnish, symbolized eternity and divine radiance. For the Mycenaean elite, burial with such treasures demonstrated not only their wealth but also their connection to the sacred. The masks thus served both personal and political functions: they honored the dead and displayed the power of the living rulers who commissioned them.

It is also possible that the masks were linked to ancestor worship. By preserving the likenesses of their forebears, Mycenaean rulers may have reinforced their claims to power, showing continuity between generations. In this sense, the masks are not only funerary objects but instruments of memory and legitimacy.

Faces from the Grave

The masks discovered at Mycenae are few in number but profoundly evocative. Among the most famous are:

- The so-called “Mask of Agamemnon,” with its finely detailed beard, almond-shaped eyes, and calm expression. Though not actually Agamemnon’s, it stands as one of the most iconic images of ancient Greece.

- Simpler masks with smoother, more abstract features, which may represent younger individuals or different artistic traditions.

- Other masks that show subtle variations in facial hair or shape, hinting at attempts to capture personal characteristics.

What unites them all is the impression of dignity and serenity. These are not grotesque death masks, but idealized, noble visages, as if the Mycenaeans sought to present their dead in a state of eternal calm and honor.

Comparisons Across Cultures

The practice of covering the face of the dead with gold is not unique to the Mycenaeans. In Egypt, pharaohs were buried with golden masks, the most famous being the mask of Tutankhamun. In the Near East and among other ancient societies, similar traditions existed.

Yet the Mycenaean masks are distinct in their simplicity. Unlike the highly ornate Egyptian masks, which often incorporated elaborate headdresses and inlays, the Mycenaean masks are minimalistic, focused solely on the face. This difference reflects cultural priorities: where Egyptians emphasized divine transformation and ritual, Mycenaeans may have emphasized individuality and earthly honor.

Such cross-cultural comparisons highlight the interconnectedness of the ancient world, as ideas and practices flowed across the Mediterranean. They also reveal how each society expressed its own values through the universal experience of death.

The Masks and the Mycenaean World

The masks must be understood as part of the broader Mycenaean funerary tradition. Grave Circle A, where they were found, contained six shaft graves with multiple burials, accompanied by weapons, jewelry, and luxury goods. These were not ordinary people—they were elites, rulers, or warriors whose status demanded extraordinary commemoration.

The masks, then, are symbols of a society stratified by power and wealth. They reflect the emergence of kingship and the consolidation of authority in the hands of ruling families. By burying their dead in such splendor, the Mycenaean elite proclaimed their dominance in life and sought to secure it in memory.

At the same time, the masks reveal something profoundly human: the desire to hold on to the face of a loved one, to capture the fleeting features of mortality in a form that defies decay. In this, the Mycenaeans were not so different from us.

Mycenaean Decline and the Silence of the Masks

By around 1100 BCE, the Mycenaean civilization collapsed. Palaces were abandoned, trade networks shattered, writing systems disappeared. The reasons remain debated—climate change, invasions, internal strife, or a combination of factors. Whatever the cause, the grandeur of Mycenae gave way to centuries of obscurity, the so-called Greek Dark Ages.

The gold masks, buried in their graves, survived the fall. For nearly three millennia they lay in silence, forgotten beneath the earth, until Schliemann’s spade brought them to light. Their survival is a reminder of the fragility of human achievement and the enduring power of material culture to outlast even the mightiest civilizations.

Modern Interpretations and Debates

Since their discovery, the gold masks of Mycenae have inspired fascination and controversy. Some scholars have questioned Schliemann’s methods, suggesting that he may have exaggerated his claims or even tampered with the artifacts. The authenticity of the so-called Mask of Agamemnon has been debated, though most evidence supports its genuineness as a Bronze Age artifact.

Others debate the masks’ meaning. Were they portraits of individuals, or idealized symbols of rank? Did they represent the deceased in life, or the role they played in society? Such questions remind us that archaeology is as much interpretation as discovery. The masks do not give up their secrets easily—they invite us to wonder, to question, to imagine.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Today, the gold masks of Mycenae are among the crown jewels of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Visitors stand in awe before their shimmering presence, feeling the tug of history and the allure of mystery. They have become symbols not only of Mycenaean Greece but of the deep continuity of Greek culture, linking the Bronze Age to the classical age, myth to reality.

The masks also continue to inspire art, literature, and scholarship. They appear in history books, documentaries, and even modern creative works, where their haunting beauty serves as a reminder of the ancient human desire to confront death with artistry and meaning.

Conclusion: Faces That Never Fade

The gold masks of Mycenaean Greece are more than archaeological treasures. They are human documents, written not in ink but in gold. They tell us of a society that honored its dead with dignity, that wielded wealth and power, that sought to capture the essence of the human face in a form that would outlast time.

They remind us that civilizations rise and fall, but the human need to remember, to honor, to give shape to mortality, endures. The masks stare back at us across three thousand years, their eyes closed yet filled with unspoken truths. In their silence, they speak of kings and warriors, of families and ancestors, of life and death.

Above all, they speak of humanity’s endless yearning for immortality—not in flesh, but in memory, in art, in gold that gleams eternally beneath the shifting light of history.