On a quiet afternoon in the summer of 1950, the physicist Enrico Fermi posed a question that would echo through decades of scientific thought and cultural imagination. During an informal conversation about extraterrestrial life, he suddenly asked, “Where is everybody?” The question was deceptively simple, almost casual, yet it contained a profound intellectual tension. Given the vastness of the universe, the enormous number of stars and planets, and the age of the cosmos itself, the absence of any clear evidence for intelligent extraterrestrial civilizations seemed puzzling. This tension, between what appears statistically likely and what we actually observe, came to be known as the Fermi Paradox.

The Fermi Paradox is not a paradox in the strict logical sense. Rather, it is a conflict between expectation and observation. Modern astronomy has revealed a universe overflowing with galaxies, each containing billions of stars, many of which host planets. If even a small fraction of these planets develop life, and if even a smaller fraction of that life evolves intelligence and technology, then the universe should be teeming with civilizations. And yet, the sky remains silent. No confirmed signals, no visiting probes, no unambiguous signs of cosmic neighbors. The paradox lies not in the absence of life itself, but in the absence of evidence for advanced, communicative civilizations.

This question touches something deeply human. It is not merely about aliens; it is about our place in the universe. Are we alone? Are we early? Are we insignificant, or uniquely fragile? The Fermi Paradox stands at the intersection of astrophysics, biology, technology, and philosophy, forcing us to confront both the immensity of the cosmos and the limits of our understanding.

A Universe Built for Possibility

To appreciate the weight of the Fermi Paradox, one must first understand just how vast and ancient the universe truly is. The observable universe contains hundreds of billions of galaxies, each with hundreds of billions of stars. Our own Milky Way alone hosts an estimated one hundred billion stars. For much of human history, stars were seen as fixed points of light, distant and unreachable. Modern astronomy has transformed them into potential suns, many accompanied by planetary systems.

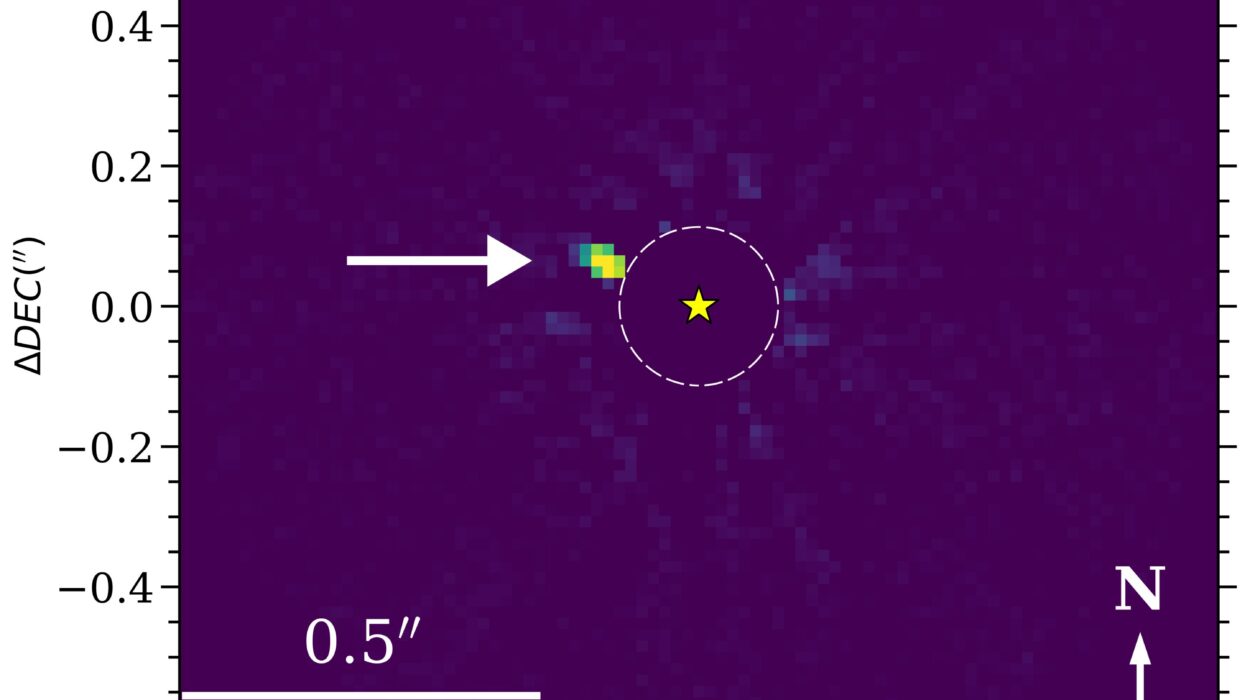

In recent decades, the discovery of exoplanets has revolutionized our view of the cosmos. Astronomers now know that planets are common, not rare. Many stars host multiple planets, and a significant number of these planets lie within regions where liquid water could exist on their surfaces under the right conditions. These so-called habitable zones suggest that environments suitable for life may be widespread.

The universe is also old. At approximately 13.8 billion years, it has had ample time for stars to form, die, and enrich space with heavy elements, and for planets to assemble from this material. Life on Earth appeared relatively early in the planet’s history, suggesting that life may arise readily when conditions allow. Intelligent life, while more complex, still emerged within a few billion years. From a cosmic perspective, this is not an especially long time.

Taken together, these facts create an expectation. The sheer scale of space and time seems to favor the emergence of many technological civilizations. Even if the probability of intelligence arising is extremely small, the number of opportunities appears overwhelmingly large. This expectation forms one side of the Fermi Paradox.

The Silence of the Sky

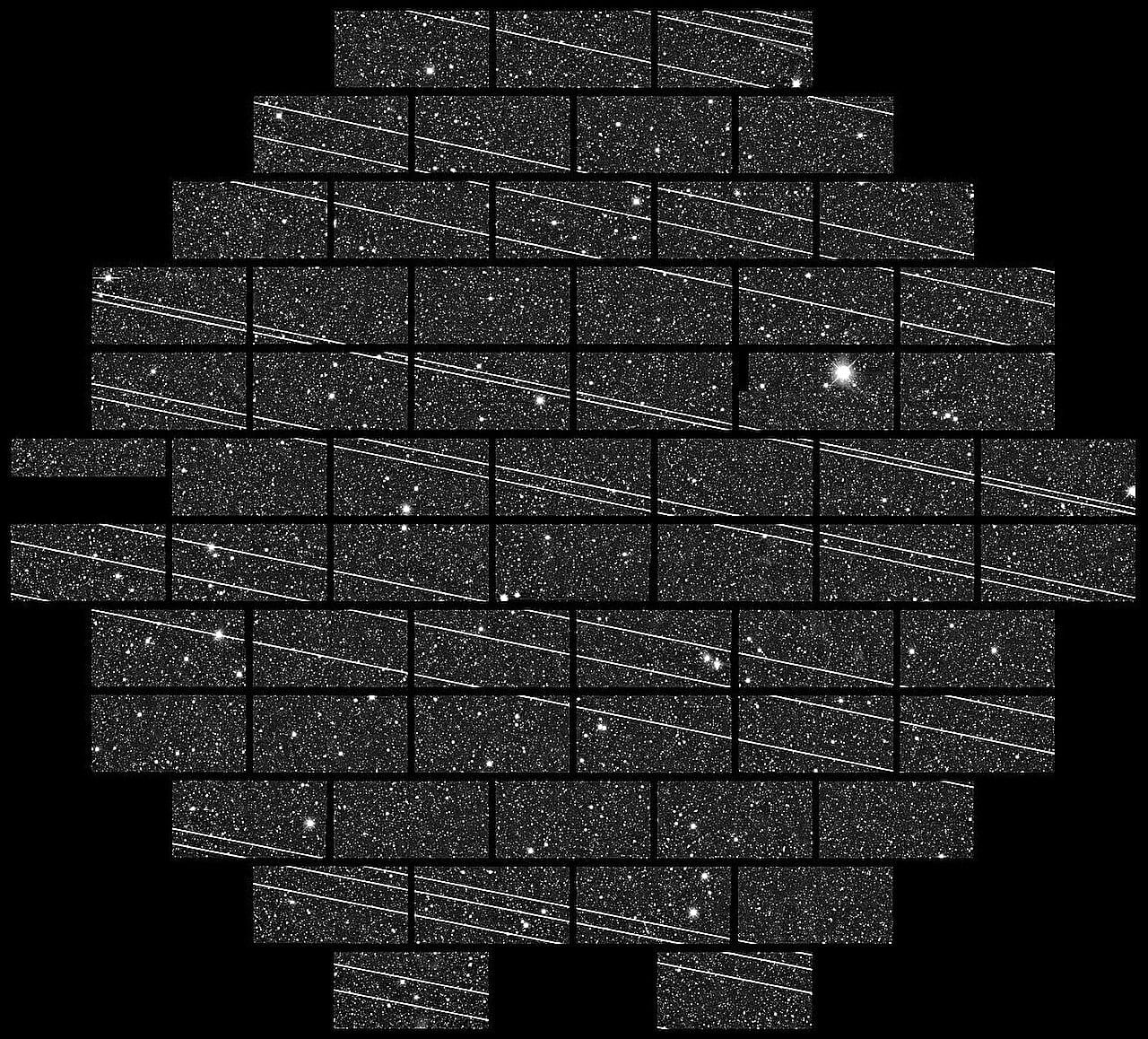

Against this backdrop of abundance stands a stark and unsettling observation: we see no clear evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence. Despite decades of searching, no verified signals from other civilizations have been detected. Radio telescopes have scanned the skies for narrowband signals that might indicate artificial transmission. Optical searches have looked for laser flashes or unusual stellar behavior. None have yielded definitive results.

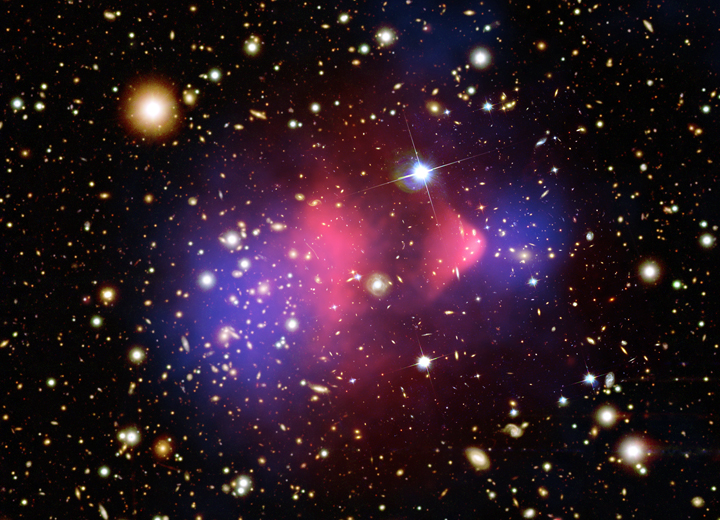

The silence is not merely a lack of communication. We also see no signs of large-scale engineering projects, such as stars partially enclosed by energy-harvesting structures, nor any unmistakable artifacts in our solar system. The laws of physics suggest that an advanced civilization could, in principle, leave detectable footprints on cosmic scales. The absence of such footprints deepens the mystery.

This silence is particularly striking when considered alongside the speed at which technological expansion could, theoretically, occur. Even traveling at speeds far below that of light, a civilization with sufficient technological capability could spread across a galaxy in a relatively short cosmic time. Compared to the age of the Milky Way, the time required for such expansion is almost negligible. If even one civilization had chosen to do so millions of years ago, its influence might already be visible.

And yet, the universe appears quiet. This discrepancy between expectation and observation is the heart of the Fermi Paradox. It challenges us to reexamine our assumptions about life, intelligence, and the nature of technological progress.

The Role of Probability and Uncertainty

At the core of the Fermi Paradox lies an uncomfortable truth: we do not know how likely life or intelligence really is. Our expectations are based on a single data point, Earth. From this lone example, we attempt to infer universal probabilities. This is a precarious position, scientifically speaking.

Life on Earth began relatively quickly after the planet became habitable, which might suggest that life arises easily. However, the transition from simple life to complex, multicellular organisms took billions of years. The emergence of technological intelligence occurred only once, and very recently, in geological terms. These facts allow for multiple interpretations. Life itself may be common, while intelligence may be exceedingly rare. Alternatively, intelligence may be common, but technological civilizations may be short-lived.

Probability plays a central role in the paradox, but it is probability under extreme uncertainty. Without additional examples of life beyond Earth, we cannot reliably estimate how often each step in the chain from chemistry to civilization occurs. The Fermi Paradox forces us to confront this uncertainty and to question whether our intuitions, shaped by a single planet, are misleading us.

The Great Filter and the Fragility of Civilization

One influential idea associated with the Fermi Paradox is the concept of the Great Filter. The Great Filter refers to one or more stages in the evolution of life that are extremely difficult to pass. These stages act as bottlenecks, drastically reducing the number of civilizations that reach a level capable of interstellar communication or expansion.

The Great Filter could lie in the past or in the future. It might be that the emergence of life itself is extraordinarily rare, requiring a delicate combination of conditions that seldom occur. Alternatively, the evolution of complex cells, sexual reproduction, or intelligence might be the true bottleneck. Each of these transitions occurred only once on Earth, and each required long periods of stability and chance.

A more unsettling possibility is that the Great Filter lies ahead of us. Technological civilizations may tend to destroy themselves through war, environmental collapse, or uncontrolled technologies before they can spread beyond their home planet. In this view, the silence of the universe is not reassuring but ominous. It suggests that longevity is rare, and that surviving the technological adolescence of a civilization may be the greatest challenge of all.

The Great Filter hypothesis does not offer a single answer; it reframes the question. The Fermi Paradox becomes not just “Where is everyone?” but “What happens to civilizations like ours?” This reframing ties the cosmic mystery directly to human choices and responsibilities.

Technology, Visibility, and the Limits of Detection

Another perspective on the Fermi Paradox focuses on the limitations of our search. The absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. Our methods for detecting extraterrestrial intelligence are still relatively primitive, and our search has covered only a tiny fraction of the possible parameter space.

Technological civilizations may not communicate in ways we expect. Radio signals, which formed the basis of early searches, may be a brief phase in a civilization’s development. Advanced societies might use communication methods that are undetectable or indistinguishable from natural phenomena. They may choose not to broadcast their presence at all, adopting a strategy of cosmic silence for reasons of security or efficiency.

Distance also matters. Signals weaken as they travel across space, and even powerful transmissions may become lost in cosmic noise over interstellar distances. Time adds another layer of difficulty. Civilizations may rise and fall over timescales that do not overlap with our own. The universe could be filled with life, yet staggered in such a way that no two technological civilizations ever coexist close enough in time to detect one another.

From this perspective, the Fermi Paradox may reflect not a lack of life, but a mismatch between our expectations and the realities of cosmic communication.

The Biological Perspective: Life as a Rare Outcome

Biology adds another dimension to the paradox. Life, as we know it, depends on complex chemistry and stable environments. While the building blocks of life appear to be widespread, assembling them into self-replicating systems may be extraordinarily difficult. The origin of life remains one of the deepest unsolved problems in science.

Even if life arises, its evolution is shaped by contingent events. Mass extinctions, climate shifts, and random mutations all influence the path life takes. On Earth, intelligence capable of technology is the result of a long chain of unlikely events. Dinosaurs dominated the planet for millions of years without developing advanced technology. It took a particular combination of ecological pressures and evolutionary pathways for humans to emerge.

This perspective suggests that intelligent life may be an evolutionary anomaly rather than a common outcome. The universe could be filled with simple life forms, perhaps even complex ecosystems, yet lack civilizations capable of building radio telescopes or spacecraft. In such a universe, the silence we observe would be expected, not paradoxical.

The Cosmic Timescale and the Question of Timing

Timing plays a subtle but crucial role in the Fermi Paradox. The universe has not always been hospitable to life. In its early stages, heavy elements necessary for planets and complex chemistry were scarce. As generations of stars lived and died, these elements became more abundant, increasing the likelihood of habitable worlds.

It is possible that we are among the first technological civilizations to emerge. In this view, the universe is only now reaching an era where conditions are favorable for advanced life. The silence of the sky would then reflect a cosmic youth rather than a cosmic emptiness.

Alternatively, we may be latecomers. Other civilizations may have risen and fallen long before we appeared, leaving no detectable traces. Given the vast timescales involved, even civilizations that lasted millions of years could be fleeting on a cosmic clock. The universe could be full of ancient ruins, now erased by time and cosmic processes.

The Fermi Paradox forces us to grapple with the enormity of cosmic time and to recognize how brief our own existence has been. Our moment of awareness may be fleeting, a narrow window in which the universe briefly looks back at itself through human eyes.

Cultural and Psychological Dimensions

The question of extraterrestrial intelligence is not purely scientific; it is also cultural and psychological. Human expectations about alien civilizations are shaped by our own history, fears, and aspirations. We often imagine others as mirrors of ourselves, projecting our tendencies toward expansion, communication, or competition onto unknown beings.

Yet there is no reason to assume that extraterrestrial intelligence would resemble human intelligence in motivation or behavior. Advanced civilizations may prioritize inward development over outward expansion. They may find interstellar travel unappealing or unnecessary. Their values, shaped by entirely different evolutionary histories, could lead them to choices that leave little observable impact on the cosmos.

The Fermi Paradox thus reflects not only uncertainty about the universe, but also uncertainty about ourselves. It challenges anthropocentric assumptions and invites humility. The universe does not owe us companions, nor does it conform to our narratives of progress and destiny.

Scientific Searches and the Continuing Mystery

Despite the uncertainty, scientists continue to search. Projects dedicated to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence employ increasingly sophisticated techniques, scanning broader ranges of frequencies and analyzing vast datasets with advanced algorithms. Astronomers study exoplanet atmospheres for chemical signatures that might indicate biological or technological activity.

These efforts are driven not by certainty, but by curiosity. The Fermi Paradox does not discourage the search; it gives it meaning. Each null result refines our understanding, narrowing the range of possibilities and sharpening the questions we ask.

Importantly, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence also deepens our understanding of Earth. By studying what makes a planet habitable and what sustains a technological civilization, we gain insight into our own planet’s fragility and value. The cosmic perspective turns the search outward, but its lessons often point inward.

What the Paradox Ultimately Asks of Us

At its deepest level, the Fermi Paradox is not simply about aliens. It is about knowledge, ignorance, and the limits of inference. It reminds us that the universe is vast beyond comprehension, and that our understanding of life and intelligence is still in its infancy.

The paradox also carries an ethical dimension. If intelligent life is rare, then preserving it becomes a profound responsibility. If civilizations tend to self-destruct, then survival is not guaranteed by intelligence alone. In contemplating the silence of the cosmos, we are prompted to consider the future of our own civilization, the choices we make, and the legacy we leave.

The question “Where is everyone?” remains unanswered, not because it is meaningless, but because it is too large to resolve with current knowledge. It stands as an invitation rather than a conclusion, urging us to explore, to question, and to listen carefully to the universe around us.

Alone or Not, the Universe Still Speaks

Whether humanity is alone or one among many, the universe is not empty of meaning. Its laws, structures, and history tell a story of remarkable coherence and beauty. The same physical principles that govern distant galaxies shape the atoms in our bodies. In seeking others, we learn more about ourselves.

The Fermi Paradox endures because it captures a fundamental tension between abundance and absence, hope and humility. It reminds us that knowledge is always provisional, and that wonder thrives in uncertainty. Until the silence is broken, or until we understand why it persists, the question will remain, echoing across space and time.

If the universe is so big, where is everyone? The answer, whatever it may be, will not only reshape our understanding of the cosmos. It will reshape our understanding of what it means to be human in a universe vast enough to hold both infinite possibility and profound solitude.