There is a moment in cosmic history that feels almost impossibly distant. Just one billion years after the Big Bang, when the universe was still in its infancy, something extraordinary was already unfolding. Stars were forming. Galaxies were assembling. And, hidden behind thick veils of dust, entire worlds were blazing with activity.

Now, a team of 48 astronomers from 14 countries, led by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, has uncovered a remarkable population of these ancient, dusty star-forming galaxies at the farthest edges of the observable universe. Their discovery, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, is not just another data point in a long list of astronomical findings. It may force scientists to rethink how the universe itself grew up.

These galaxies existed nearly 13 billion years ago, not long after the Big Bang, which is believed to have taken place 13.7 billion years ago. They appear to represent a missing chapter in the grand narrative of galactic evolution—a transitional stage that connects some of the earliest, brightest galaxies to others that mysteriously “died” young.

To understand why this matters, we have to begin with the dust.

Galaxies Hidden in the Dark

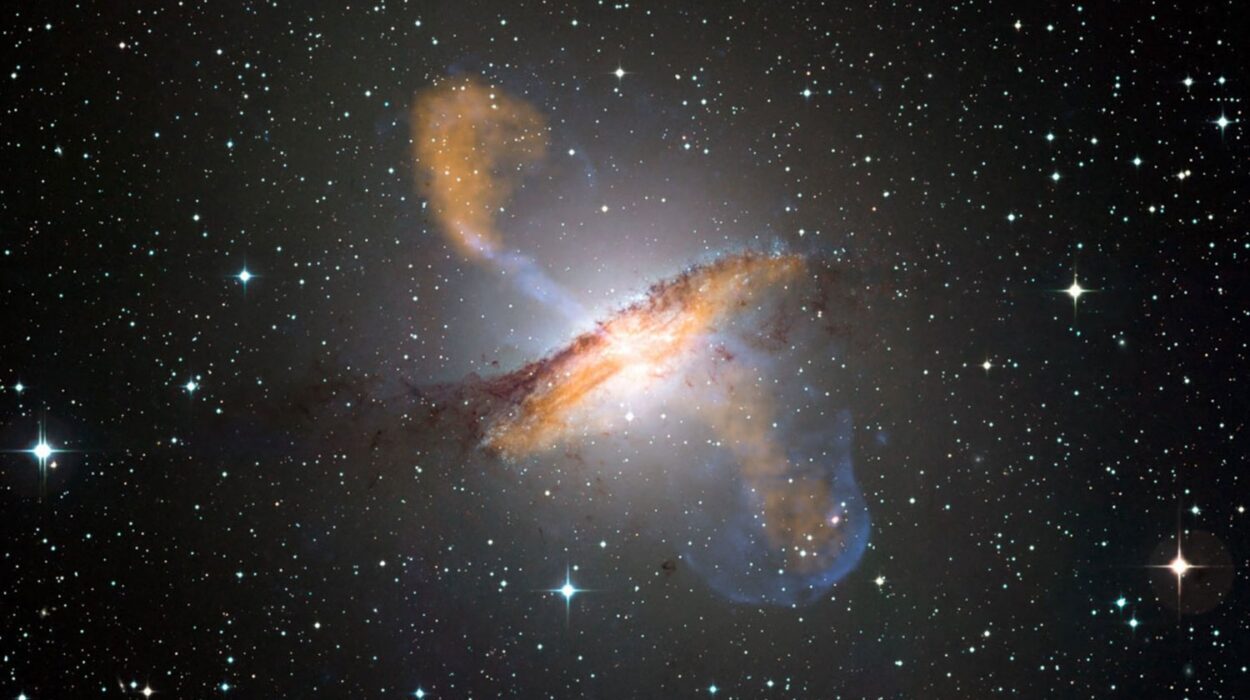

For decades, astronomers have known about a rare population of galaxies so enshrouded in cosmic dust that they are nearly invisible to conventional telescopes. These galaxies are massive and intensely active, forming stars at remarkable rates. But the very process that makes them shine also cloaks them in obscurity.

Dust absorbs ultraviolet and visible light, effectively hiding these galaxies from instruments that rely on those wavelengths. To traditional telescopes, they simply fade into darkness.

Jorge Zavala, assistant professor of astronomy at UMass Amherst and lead author of the study, has spent years chasing these elusive objects. He explains that these dusty galaxies were only discovered in the late 1990s, and even then, they remained frustratingly difficult to study. The dust that swaddles them acts like a cosmic curtain.

But dust does more than obscure. It transforms.

When dust absorbs ultraviolet and visible light, it heats up. That heat is then re-emitted as infrared radiation, at longer wavelengths. And that subtle shift—from visible light to longer wavelengths—opened a new window onto the universe.

New Eyes for an Ancient Universe

The breakthrough came with the development of submillimeter telescopes, instruments capable of detecting the longer-wavelength glow of heated dust. Suddenly, astronomers could peer into regions of space that had once seemed empty.

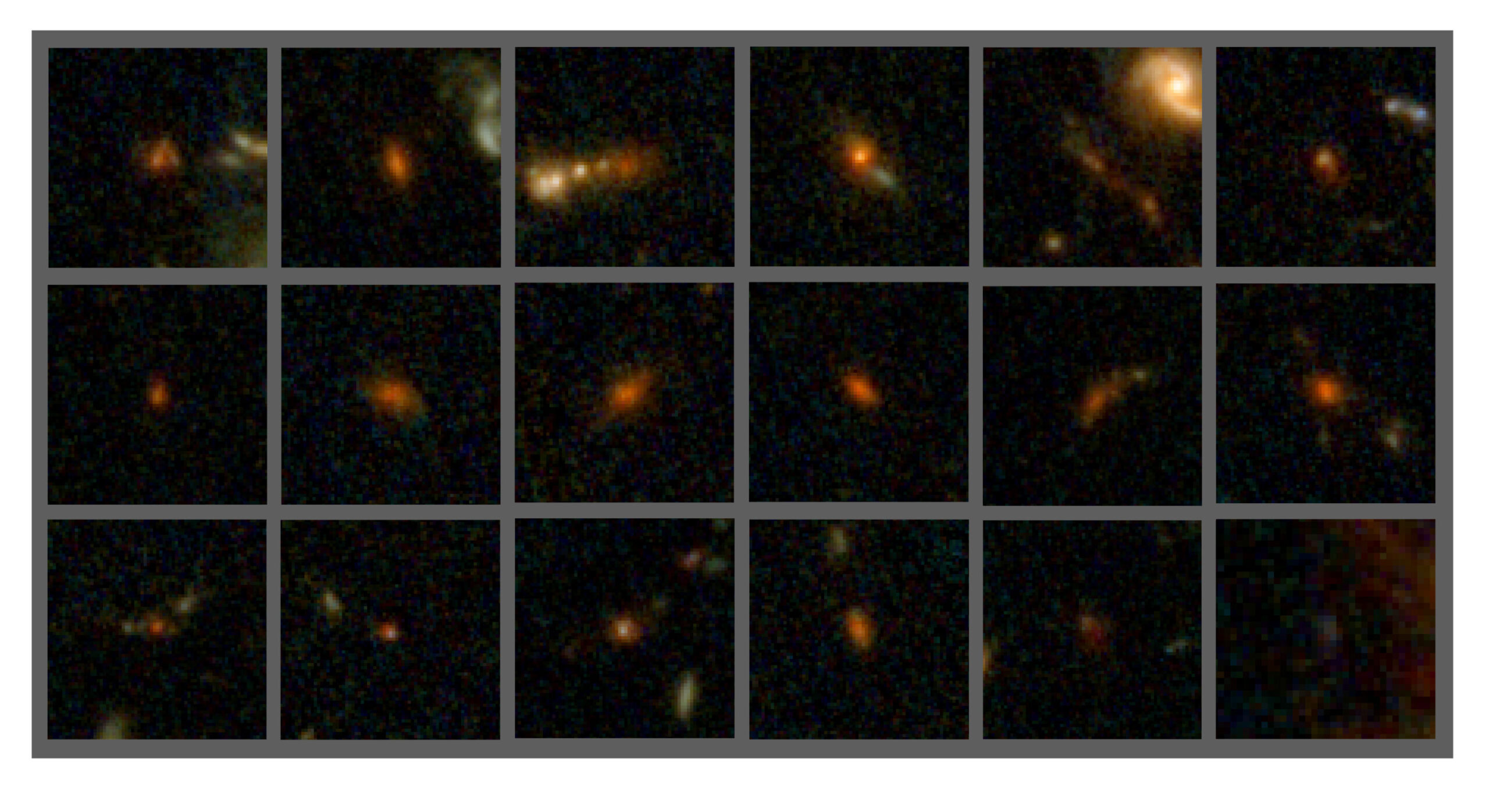

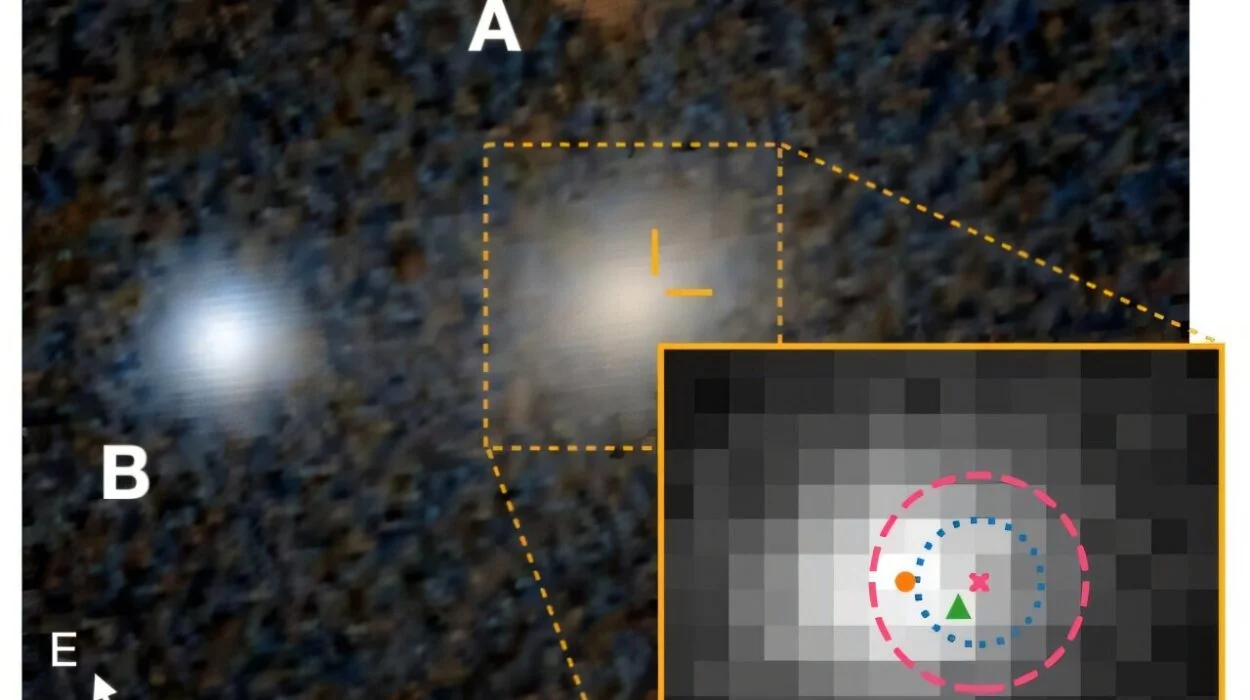

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, commonly known as ALMA, located in Chile, Zavala and his collaborators identified about 400 bright, dusty galaxies. These were luminous, powerful systems, glowing in the submillimeter range.

But the team wanted to go deeper. They wanted to find the faintest members of this hidden population—the galaxies lurking at the very boundary of the observable cosmos.

To do that, they turned to one of astronomy’s newest and most powerful tools: the James Webb Space Telescope. With its advanced near-infrared observations, this telescope allowed researchers to detect approximately 70 faint dusty galaxy candidates, most of which had never been seen before.

Even then, confirmation required patience and ingenuity. The team returned to the ALMA data and used a technique known as “stacking”, combining multiple observations to strengthen the faint signals. The result was clear. These galaxies were real, and they were ancient.

They had formed almost 13 billion years ago.

Snapshots of a Galactic Life

The discovery is technically impressive, but its true importance lies in what it reveals about the timeline of the universe.

Dusty galaxies are not small, primitive systems. They are massive galaxies rich in metals and cosmic dust. Metals, in astronomical terms, are elements forged in the hearts of stars. Their presence means that multiple generations of stars must already have lived and died to create them.

In other words, significant star formation had already occurred—far earlier than many current models predict.

Even more intriguing is how these newly identified galaxies fit into a broader cosmic puzzle. In recent years, astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have discovered ultradistant, ultrabright star-forming galaxies that appeared astonishingly soon after the Big Bang—around 13.3 billion years ago. These galaxies were youthful and intensely luminous, bursting with star birth.

At the other end of the spectrum are early “quiescent” galaxies, massive systems that had already stopped forming stars roughly two billion years after the Big Bang. These galaxies are sometimes described as “dead,” their stellar factories shut down.

What Zavala and his team may have found is the missing middle.

He describes it almost like flipping through a cosmic photo album. The ultrabright galaxies are the energetic children, newly formed and ablaze with star formation. The quiescent galaxies are the elders, quiet and settled, their active years behind them. And these dusty galaxies, newly confirmed at the edge of time, appear to be the young adults—mature enough to be massive and metal-rich, yet still actively forming stars.

For the first time, astronomers may be seeing consecutive snapshots of a rare galaxy population’s life cycle.

Challenging the Cosmic Script

If this interpretation holds, it carries profound implications.

Current models of cosmic evolution attempt to explain how matter assembled into stars and galaxies over billions of years. They predict when star formation should have ramped up, how quickly galaxies should have grown, and when massive systems should have emerged.

But these dusty galaxies seem to have matured too quickly.

They are old—nearly 13 billion years old from our perspective—and yet already massive, already rich in metals, already brimming with dust. Their existence suggests that star formation occurred earlier in the universe’s evolution than previously thought.

That means something is missing from our theoretical framework.

Perhaps the processes that drive star formation were more efficient in the early universe than models account for. Perhaps galaxies assembled faster. Perhaps the timeline of cosmic growth needs revision.

The researchers are cautious. Much more study will be required to confirm whether these galaxies truly represent a transitional phase in a single evolutionary sequence. Astronomy is a field built on careful verification, and extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence.

Still, the pieces are aligning in a way that is hard to ignore.

Why This Changes Our Story of the Universe

At first glance, dusty galaxies might seem like a niche topic, buried deep in technical journals and distant observatories. But their significance reaches much further.

Every model of the universe tells a story about how we came to be. The atoms in our bodies were forged in ancient stars. The heavy elements that make planets possible were created in stellar furnaces long ago. Understanding when and how those first generations of stars formed is, in a real sense, understanding our own origins.

If star formation began earlier and progressed faster than we believed, then the universe’s timeline shifts. The early cosmos becomes a more dynamic, more productive place than our models suggest. The first billion years after the Big Bang were not just a slow gathering of matter but a time of intense, rapid transformation.

This discovery adds a crucial chapter to that story.

By revealing a population of dusty, massive, metal-rich galaxies formed just one billion years after the Big Bang, Zavala and his colleagues have illuminated a hidden era of cosmic adolescence. They have shown that the universe may have grown up faster than we imagined.

And in doing so, they remind us of something fundamental about science. The universe is not obligated to follow our expectations. Each new telescope, each new technique, peels back another layer of the unknown. Sometimes what we find fits neatly into place. Sometimes it demands that we rewrite the script.

Here, at the edge of time, in the faint glow of ancient dust, the universe is whispering that its story is more complex—and more astonishing—than we thought.

Study Details

Jorge A. Zavala et al, ALMA and JWST Identification of Faint Dusty Star-forming Galaxies up toz ∼ 8 and Their Connection with Other Galaxy Populations, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2026). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae382a