Sleep is one of the most fundamental needs of human life—so basic that we often take it for granted. We eat, we breathe, we sleep. Yet, unlike food or oxygen, sleep feels intangible, as if its importance can be overlooked in the rush of daily life. We cut back on it to study, to work, or to scroll through screens late into the night, believing we can simply “catch up” later. But sleep is not optional. It is a biological necessity that profoundly shapes how we think, feel, and function.

Perhaps nowhere is the connection more powerful than between sleep and mental health. Poor sleep clouds our thoughts, heightens our emotions, and weakens our ability to cope with stress. In contrast, restful sleep strengthens resilience, stabilizes mood, and sharpens memory. Scientists now recognize that sleep and mental health are so deeply connected that they can no longer be seen as separate. To understand one, we must understand the other.

The Science of Sleep: A Hidden World Within Us

Sleep may feel like stillness, but biologically it is a remarkably active process. During the night, our brains cycle through different stages:

- Non-REM sleep (NREM): Includes light sleep (Stages 1 and 2) and deep sleep (Stage 3, often called slow-wave sleep). Deep sleep is when the body repairs tissues, strengthens the immune system, and consolidates physical memory.

- REM sleep (Rapid Eye Movement): This is the stage where dreams occur, and the brain processes emotions, creativity, and learning. REM sleep is essential for mental restoration.

A typical night includes 4–6 cycles of these stages, lasting about 90 minutes each. Disruptions—whether from stress, insomnia, or external disturbances—can shatter this cycle, leaving the brain unfinished in its nightly work.

This nightly rhythm is governed by two systems: the circadian rhythm, our internal body clock influenced by light and darkness, and sleep pressure, a biological drive that builds up the longer we’re awake. When both systems are in harmony, sleep feels natural. When disrupted—by late-night screen exposure, caffeine, or irregular schedules—our health pays the price.

Sleep and the Emotional Brain

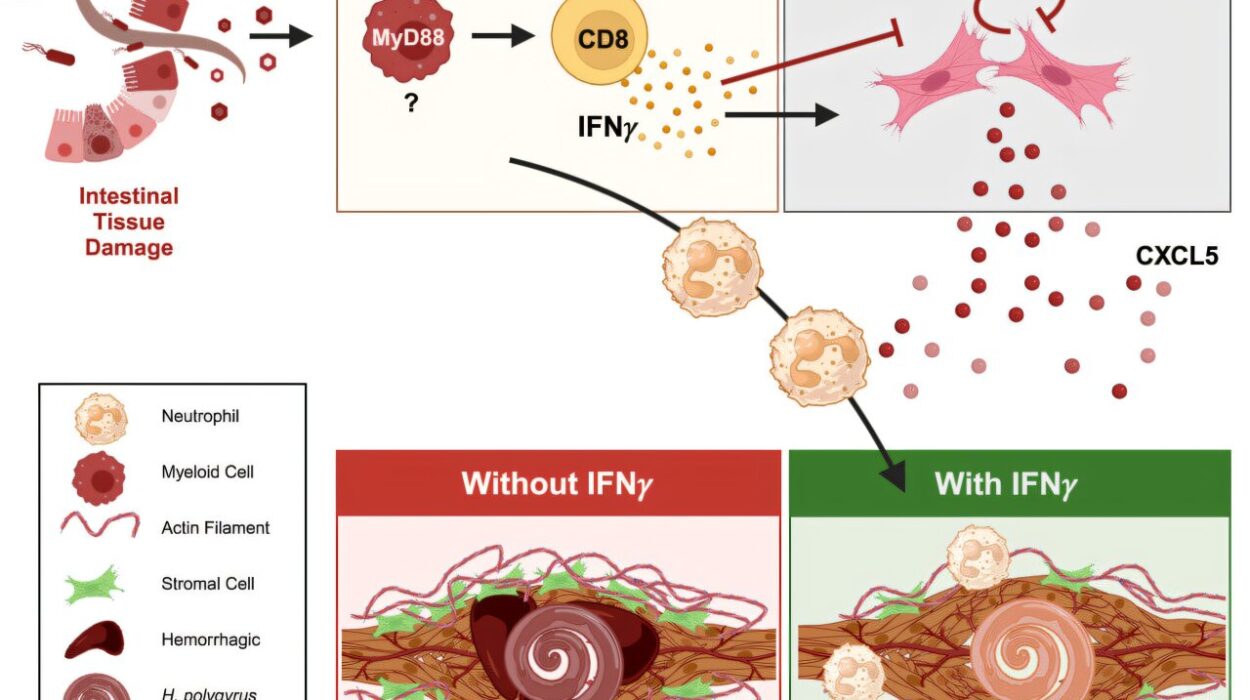

The link between sleep and emotions is profound. Studies using brain imaging show that sleep deprivation amplifies activity in the amygdala—the brain’s emotional alarm system—by up to 60%. At the same time, the prefrontal cortex, which regulates emotional responses, becomes less active. The result? A brain that is emotionally reactive but less capable of self-control.

This explains why after a sleepless night we feel irritable, anxious, or quick to anger. Even small stressors seem overwhelming. Without enough rest, our brains tilt toward negativity, making us more vulnerable to sadness and frustration.

On the other hand, good sleep acts as emotional first aid. During REM sleep, the brain replays and processes emotional experiences, almost like overnight therapy. Distressing events are revisited in dreams but with stress chemicals like norepinephrine turned down, allowing us to process emotions without being overwhelmed. This is one reason why a night of good sleep can make yesterday’s pain feel more bearable.

Sleep and Stress: A Two-Way Street

Stress and sleep have a circular relationship. Stressful days often lead to restless nights, as the brain races with worry and the body produces stress hormones like cortisol. Elevated cortisol keeps us alert, making it harder to fall asleep. Then, sleep loss heightens stress reactivity, creating a vicious cycle.

Chronic stress disrupts the circadian rhythm, reduces deep sleep, and keeps the nervous system in a constant state of hyperarousal. This cycle contributes to burnout, anxiety disorders, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Conversely, learning to manage stress—through relaxation techniques, exercise, or mindfulness—can restore healthy sleep and protect mental well-being.

Sleep and Anxiety

Anxiety and sleep problems are almost inseparable. About 90% of people with anxiety disorders report difficulties with sleep. Insomnia is not just a symptom but also a driver of anxiety. When the mind lacks the chance to reset during deep and REM sleep, intrusive thoughts and hyperarousal grow stronger.

Sleep-deprived brains show heightened activity in the insula and amygdala, regions associated with fear. This explains why sleepless nights can trigger racing thoughts, panic attacks, and exaggerated worry. Over time, poor sleep can even raise the risk of developing clinical anxiety disorders.

Fortunately, the relationship also works in reverse: improving sleep often reduces anxiety. Therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) help individuals calm their thoughts at night, regulate their sleep patterns, and reduce daytime anxiety.

Sleep and Depression

Depression and sleep are bound together in complex ways. Roughly 75% of people with depression experience insomnia, while others experience hypersomnia—sleeping too much but still feeling unrefreshed.

Sleep deprivation can worsen depression by disrupting the brain’s ability to regulate mood and reward systems. The neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine—all critical for mood—are affected by poor sleep. Furthermore, REM sleep abnormalities are common in depression, with people entering REM too quickly and experiencing less restorative deep sleep.

Yet, sleep also offers surprising therapeutic potential. In some cases, carefully controlled sleep deprivation (paradoxically) has been shown to produce rapid but short-lived improvements in depressive symptoms, suggesting that sleep and mood regulation are intricately linked.

Sleep and Bipolar Disorder

For individuals with bipolar disorder, sleep is both a warning sign and a trigger. Insomnia or reduced need for sleep can precede manic episodes, while hypersomnia often accompanies depressive episodes. Disrupted circadian rhythms appear to play a central role in bipolar disorder, and stabilizing sleep patterns is a cornerstone of treatment.

Light therapy, melatonin regulation, and strict sleep schedules are often recommended alongside medication. Research shows that when people with bipolar disorder maintain regular, restorative sleep, mood swings become less frequent and less severe.

Sleep and Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia, a severe mental illness involving psychosis, hallucinations, and cognitive disruption, is strongly associated with sleep disturbances. Many patients experience fragmented sleep, reduced deep sleep, and irregular circadian rhythms. These sleep issues often appear before psychotic episodes, making them potential early warning signs.

Moreover, poor sleep worsens cognitive symptoms, making attention, memory, and decision-making even harder. Addressing sleep through behavioral therapy, lifestyle changes, and sometimes medications can significantly improve quality of life for individuals with schizophrenia.

Sleep and ADHD

Children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) frequently experience sleep problems, including difficulty falling asleep, restless nights, and irregular schedules. Lack of sleep worsens symptoms like inattention, impulsivity, and emotional regulation.

Sleep disruption in ADHD may be linked to delayed circadian rhythms and differences in melatonin production. Addressing these sleep difficulties—through structured routines, reduced evening screen time, and sometimes melatonin supplements—can reduce ADHD symptoms and improve focus.

Sleep and Memory, Learning, and Creativity

Mental health is not only about emotions but also about cognition—the ability to think, learn, and create. Sleep is vital for these processes.

- Memory consolidation: During deep sleep, the hippocampus replays daily experiences, transferring them into long-term storage. Without sleep, memories fade and learning suffers.

- Problem-solving and creativity: REM sleep fosters novel connections between ideas. Many scientists, artists, and inventors have had breakthroughs after a good night’s sleep or even a nap.

- Attention and focus: Sleep deprivation reduces concentration, making tasks feel harder and increasing mistakes. Chronic sleep loss impairs productivity and decision-making in ways similar to alcohol intoxication.

This means sleep is not just “rest” but active mental work. When we shortchange sleep, we sabotage our intellectual and creative potential.

The Role of Circadian Rhythms in Mental Health

Circadian rhythms—the body’s internal clock—play a huge role in both sleep and mental health. These 24-hour cycles regulate hormone release, body temperature, and sleep-wake patterns. Disruptions to circadian rhythms, such as shift work, jet lag, or late-night screen exposure, increase the risk of depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.

Light exposure is especially powerful. Morning sunlight resets the circadian clock, promoting wakefulness during the day and melatonin release at night. Lack of natural light, particularly during winter, contributes to seasonal affective disorder (SAD), a form of depression tied to daylight cycles.

Sleep Disorders and Mental Health

Several sleep disorders directly affect mental well-being:

- Insomnia: Chronic difficulty falling or staying asleep. Strongly linked to anxiety and depression.

- Sleep apnea: Interrupted breathing during sleep leads to daytime fatigue and cognitive decline. Associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety.

- Narcolepsy: Sudden sleep attacks disrupt daily life and increase risk of mental health problems.

- Restless leg syndrome (RLS): Uncontrollable urge to move the legs disrupts sleep and often leads to irritability and mood disorders.

Treating these disorders improves not only sleep quality but also mental health outcomes.

Lifestyle, Sleep, and Mental Well-Being

Sleep is not entirely out of our control. Certain habits, collectively called sleep hygiene, play a major role in protecting both sleep and mental health:

- Keeping a consistent sleep schedule, even on weekends

- Avoiding caffeine, nicotine, and heavy meals before bed

- Creating a dark, quiet, cool bedroom environment

- Reducing screen exposure an hour before bedtime

- Practicing relaxation techniques like meditation or deep breathing

- Getting daily exercise and natural light exposure

Small changes can produce dramatic improvements. In fact, behavioral strategies are often more effective than medication for chronic insomnia.

When Sleep Becomes Therapy

Sleep itself is now being explored as therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is one of the most effective treatments for sleep problems and is increasingly recognized as a powerful tool for improving mental health. By restructuring negative beliefs about sleep, setting consistent routines, and teaching relaxation techniques, CBT-I addresses both insomnia and the mental health issues linked to it.

In hospitals and clinics, improving sleep is now considered a vital part of treating depression, anxiety, PTSD, and bipolar disorder. The recognition is clear: without sleep, recovery is incomplete.

The Future of Sleep and Mental Health Research

Modern neuroscience is only beginning to unravel the mysteries of sleep. Advanced brain imaging, genetic studies, and wearable sleep trackers are revealing new insights every year. Future research may allow us to tailor sleep therapies to individual needs, prevent mental health disorders before they emerge, and use sleep as a biomarker for diagnosis.

One exciting area is the exploration of targeted memory reactivation, where sensory cues presented during sleep help reinforce positive memories. Another is the use of artificial light to precisely manipulate circadian rhythms for therapeutic purposes. These innovations suggest a future where sleep is not just understood but actively harnessed for mental health.

Sleep as the Foundation of Mental Wellness

To understand the connection between sleep and mental health is to recognize that the two are inseparable. Sleep is not a luxury or an afterthought—it is the bedrock upon which mental stability rests. Without it, the brain falters; with it, the brain heals, learns, and grows.

Every night, when we close our eyes, we give our minds the chance to repair emotional wounds, strengthen memory, and restore balance. Sleep is not wasted time—it is sacred time, the foundation of resilience, clarity, and joy.

In the end, the question is not whether sleep affects mental health, but how much of our mental health depends on sleep. The answer, as science shows, is almost everything.