Every moment, your brain hums with electrical activity—thinking, remembering, feeling, and sensing. But all this work produces biological “trash”: waste molecules and byproducts that must be cleared away to keep the brain healthy. For decades, scientists wondered how this vital cleanup happened. Unlike the rest of the body, the brain doesn’t have a conventional lymphatic drainage system, the network of vessels that removes waste and excess fluid from tissues. So how does the brain take out its trash?

A groundbreaking new study from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) may have finally revealed a key piece of this mystery. For the first time in humans, researchers have found evidence that a major artery in the brain—the middle meningeal artery (MMA)—also serves as a crucial hub in the brain’s lymphatic drainage system. The discovery opens an entirely new understanding of how the brain keeps itself clean and healthy, with profound implications for diseases like Alzheimer’s, traumatic brain injury, and even psychiatric disorders.

A Discovery Rooted in Curiosity and Collaboration

The research, published in iScience, was led by Dr. Onder Albayram, an associate professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at MUSC. Albayram and his team partnered with NASA scientists, taking advantage of real-time MRI technologies originally developed to study how spaceflight affects fluid movement in the brain.

Using these cutting-edge imaging tools, the team observed the flow of cerebrospinal and interstitial fluid—the clear liquid that cushions and cleans the brain—in five healthy volunteers over a six-hour period. What they found was striking: fluid moved slowly and steadily along the middle meningeal artery, but not in the way blood usually flows.

“We saw a flow pattern that didn’t behave like blood moving through an artery; it was slower, more like drainage, showing that this vessel is part of the brain’s cleanup system,” said Albayram.

The key observation was that the flow was passive, not driven by the pulsing force of the heart. This suggested that what they were seeing was not blood, but lymphatic fluid—a hallmark of the body’s waste-clearing system.

The Brain’s Protective Layers and the Pathways Within

To understand why this finding matters, it helps to look at the structure surrounding the brain. The brain and spinal cord are enclosed by three protective membranes known collectively as the meninges. For a long time, scientists believed these membranes formed a kind of barrier, isolating the brain from the body’s immune and lymphatic systems.

But Albayram’s work has steadily dismantled that assumption. Over the past decade, his research has shown that the meninges contain lymphatic vessels—tiny channels that connect the brain to the body’s broader lymphatic system. These vessels appear to carry waste and immune cells away from the brain, just as lymphatic vessels do elsewhere in the body.

His 2022 study, published in Nature Communications, was among the first to visualize these meningeal lymphatic vessels in humans. The new iScience study builds on that foundation, not just showing their existence but demonstrating how they actually work—how fluids move through them in real time.

Seeing the Brain’s Cleanup System in Action

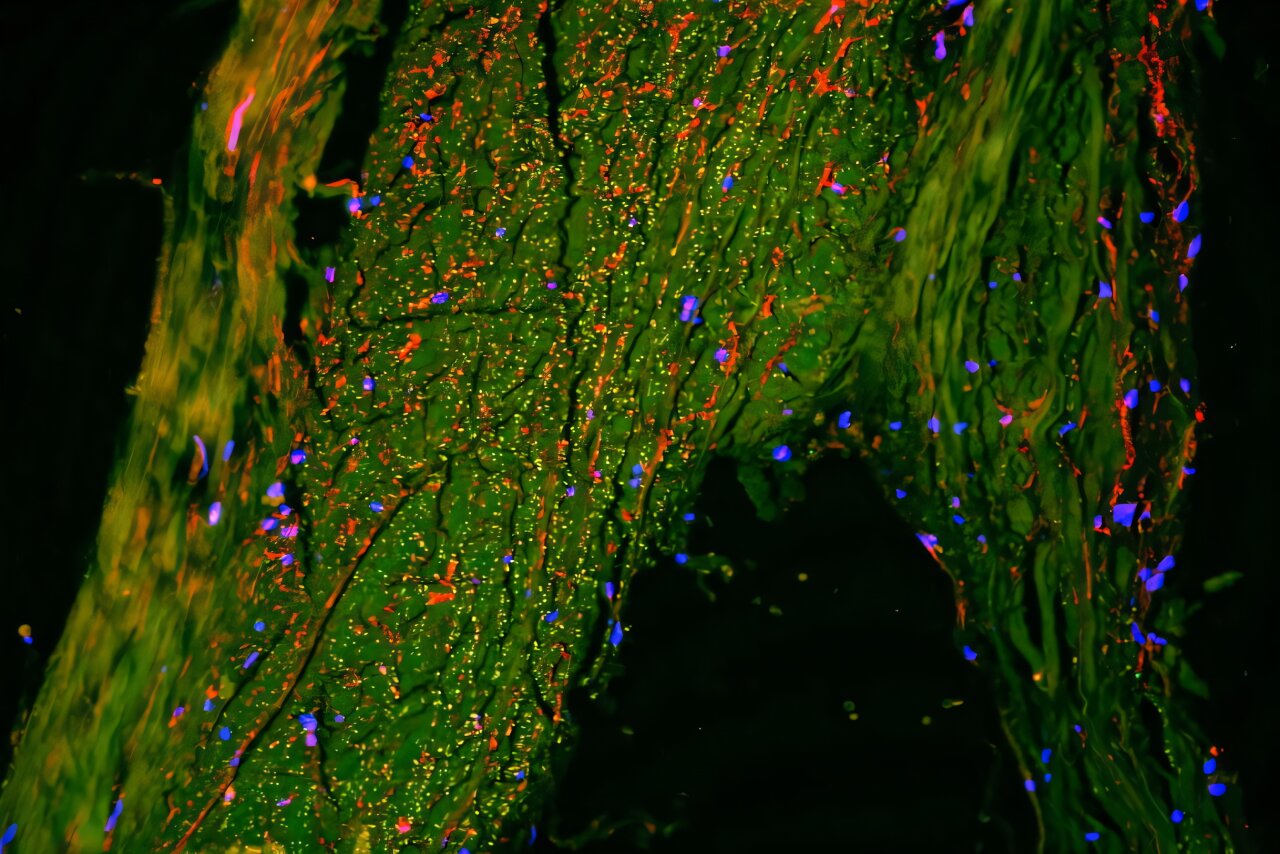

After identifying the unusual flow patterns on MRI, Albayram’s team wanted to confirm what they were seeing. To do so, they turned to high-resolution imaging of postmortem human brain tissue. Collaborating with scientists at Cornell University, they used an advanced technique that allows many cell types to be visualized simultaneously.

This detailed mapping revealed that the area around the middle meningeal artery was lined with lymphatic endothelial cells—specialized cells found only in the body’s lymphatic vessels. This cellular signature confirmed that the fluid flow seen on MRI was indeed lymphatic, not blood.

The discovery offered both structural and functional proof of a new drainage pathway inside the human brain—a connection between a major artery and the brain’s hidden waste-removal network.

Understanding How the Brain Cleans Itself

The human body’s lymphatic system plays a vital housekeeping role. It drains excess fluid from tissues, carries immune cells, and removes waste. The brain, long thought to be isolated from this process, clearly participates in a similar cycle.

Within the brain, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulates through the ventricles and around the brain and spinal cord, bathing neural tissue and collecting metabolic waste. The discovery of lymphatic vessels in the meninges—and now the identification of the MMA as a drainage hub—helps explain how this fluid ultimately exits the brain.

By moving waste-laden CSF and interstitial fluid into the body’s lymphatic system, the brain effectively “takes out its trash.” If this process slows down or becomes blocked, waste could accumulate, potentially contributing to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other disorders associated with inflammation and aging.

Why This Discovery Matters

Albayram’s findings are more than a scientific curiosity—they could reshape how we understand, diagnose, and treat brain diseases. Many neurological conditions are linked to problems in waste clearance. For instance, in Alzheimer’s disease, toxic proteins like amyloid-beta build up in the brain over time. If the lymphatic drainage pathways are impaired, the brain’s ability to remove these harmful molecules could be severely compromised.

Similarly, after a traumatic brain injury, the delicate balance of fluid flow and clearance can be disrupted, leading to inflammation and secondary damage. By identifying the normal routes and behavior of lymphatic drainage in healthy brains, scientists can begin to detect where these systems fail in disease.

As Albayram explains, “A major challenge in brain research is that we still don’t fully understand how a healthy brain functions and ages. Once we understand what ‘normal’ looks like, we can recognize early signs of disease and design better treatments.”

Rethinking the Brain’s Connection to the Body

For centuries, neuroscientists believed that the brain was a privileged organ, walled off from the rest of the body by the blood-brain barrier and immune isolation. That view is changing rapidly. The discovery of lymphatic vessels in the meninges—and now the role of the middle meningeal artery in draining brain waste—suggests a far more integrated system.

The brain is not an isolated island but part of a dynamic conversation with the immune and lymphatic systems. This connection may influence not only neurological diseases but also psychiatric conditions, as inflammation and immune responses are increasingly linked to mood disorders and cognitive decline.

Understanding how the brain communicates with the body’s immune system could eventually help scientists develop therapies that harness or restore these natural connections.

Technology Born in Space, Applied to the Mind

One of the most remarkable aspects of this study is how it bridges space research and neuroscience. The advanced MRI technologies used in this work were initially developed through a NASA partnership to study how microgravity affects fluid dynamics in astronauts’ brains.

In space, without gravity pulling fluids downward, astronauts often experience shifts in pressure and swelling in the head that can affect vision and brain function. The same imaging tools designed to monitor those changes in space proved ideal for tracking subtle, slow-moving lymphatic flow within the brain on Earth.

This cross-disciplinary approach—combining aerospace research, medical imaging, and neuroscience—highlights how innovation in one field can unlock discoveries in another.

Building the Foundation for Future Medicine

The implications of Albayram’s work stretch across the spectrum of brain health. If researchers can map exactly how lymphatic drainage works in healthy individuals, they can begin to detect early deviations linked to disease. Such insights could lead to new diagnostic imaging methods, early detection of neurodegenerative changes, and even targeted therapies to restore proper fluid clearance.

For example, enhancing lymphatic flow could become a strategy to help the brain eliminate toxic proteins before they accumulate to harmful levels. Similarly, understanding how drainage changes with age could offer new ways to slow cognitive decline or improve recovery after injury.

These are ambitious goals, but every advance begins with understanding the fundamentals. The identification of the middle meningeal artery as a new lymphatic hub marks a turning point—a clearer picture of the brain’s inner plumbing system that keeps it functioning smoothly.

The Mystery of the Aging Brain

As humans live longer, understanding how the brain ages becomes ever more crucial. Aging is accompanied by gradual changes in circulation, metabolism, and inflammation—all of which may affect the efficiency of lymphatic drainage.

If the brain’s waste-clearance pathways slow down with age, that could help explain why older adults are more susceptible to neurodegenerative conditions. Researchers like Albayram hope that by studying these processes in healthy young individuals, they can establish a baseline against which age-related changes can be measured.

This could open the door to preventive approaches—keeping the brain’s drainage systems clear and functional long before symptoms appear.

A New Paradigm for Neuroscience

Albayram’s philosophy is simple yet revolutionary: start with humans, not just animal models. By observing how the human brain functions in real time, his team aims to build a direct understanding of our unique physiology before translating those insights into experimental models.

This approach represents a shift in neuroscience—a move toward studying the brain as an integrated part of the living human body, connected to immune, vascular, and lymphatic systems. It is a holistic view that could redefine how we think about brain health.

Looking Ahead

The discovery of a new lymphatic drainage hub in the middle meningeal artery is more than a breakthrough in anatomy—it is a revelation about how the brain maintains itself. It challenges long-held assumptions, deepens our understanding of the brain’s connection to the body, and points the way toward future treatments for devastating diseases.

The brain, it turns out, is not a closed fortress but a living, breathing organ in constant dialogue with the rest of the body. Its ability to cleanse itself may hold the key to preserving memory, protecting against disease, and ensuring mental vitality across the lifespan.

As researchers continue to map the brain’s hidden highways of fluid and waste, we come one step closer to unlocking the ultimate mystery of human consciousness—how this intricate organ sustains itself, heals itself, and allows us to think, dream, and be.

More information: M. Albayram et al, Meningeal lymphatic architecture and drainage dynamics surrounding the human middle meningeal artery, iScience (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113693