What makes you… you? Is it the shape of your smile, the texture of your voice, the color of your eyes? Or is it something deeper—more mysterious—like the way you think, the emotions you feel, and the invisible wiring that sparks your preferences, fears, dreams, and decisions?

Personality has fascinated humans for thousands of years. Ancient philosophers believed it was governed by the balance of bodily fluids—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Others attributed it to the stars or divine will. But today, we look inward. Specifically, we look to the brain—a soft, wrinkled, three-pound organ floating inside your skull, pulsing with electricity and chemical messages. It’s here, neuroscientists now believe, that the core of our personality resides.

But is that the whole truth? Can we really explain identity, choice, and character by mapping synapses and neurotransmitters? Or is personality more than just brain matter—something that emerges from experience, culture, relationships, and perhaps even mystery?

This is the story of personality through the lens of neuroscience: emotionally charged, fiercely debated, and still unfolding.

The Birth of Brain Science and the Personality Puzzle

The link between the brain and behavior wasn’t always obvious. For centuries, the brain was considered a cooling system for blood—an organ of little importance. That changed slowly, over generations of observation, injury, and curiosity.

Perhaps the most famous case that ignited the modern science of brain and personality was that of Phineas Gage. In 1848, the 25-year-old railroad worker was packing gunpowder into rock with a metal rod when the charge exploded, and the iron rod shot through his skull, entering his cheek and exiting through the top of his head. Miraculously, he survived. But something had changed.

Once responsible, kind, and dependable, Gage became impulsive, rude, and erratic. Friends said he was “no longer Gage.” His personality had been altered by trauma to his frontal lobes—regions of the brain now known to play critical roles in decision-making, self-control, and social behavior.

This astonishing case cracked open a door into a new realm of science: the brain as the seat of personality. What had once seemed mystical or purely spiritual began to appear biological. A self, it seemed, could be damaged, rewired, or lost.

Frontal Lobes and the Art of Being Human

The frontal lobes, particularly the prefrontal cortex, are among the most recently evolved parts of the human brain. They are disproportionately large in humans compared to other species and are deeply involved in what we consider the essence of personality: reasoning, empathy, foresight, and the ability to regulate emotions.

Damage to this region doesn’t just affect memory or intelligence—it alters temperament. Patients may lose their sense of morality or develop poor judgment. They might act without considering consequences or say things that are socially inappropriate.

Functional MRI (fMRI) studies show that the prefrontal cortex lights up during moral dilemmas, planning activities, and when suppressing impulses. It’s the seat of the “inner voice” that weighs right from wrong and envisions futures not yet lived.

But personality is more than inhibition. Other regions play unique roles. The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure deep in the brain, contributes emotional color to experience. When damaged or underdeveloped, as seen in rare conditions like Urbach-Wiethe disease, fear responses may disappear entirely.

People with underactive amygdalas may struggle with recognizing emotions in others or feeling anxiety themselves. This leads scientists to believe that traits like fearfulness, emotional sensitivity, and even certain types of empathy have neurological underpinnings.

The Nature of Temperament: Are We Born This Way?

Long before we make conscious choices or have memories, we display temperament—patterns of behavior and emotional response that emerge in infancy. Some babies are calm and curious, others fussy and reactive. These early signs are not random. Twin studies and adoption research consistently show that temperament has a heritable component, often attributed to genetic influences on brain structure and chemistry.

The field of behavioral genetics explores how much of personality is determined by genes versus environment. Twin studies suggest that between 30% to 60% of personality traits are genetically influenced. Identical twins raised apart often show astonishing similarities in values, quirks, fears, and even political beliefs.

Does that mean we’re prisoners of our genes? Not quite. Genes may set the stage, but environment writes much of the script. A child born with a predisposition to anxiety may thrive in a nurturing, stable home or develop disorders in a chaotic one. This interplay—what scientists call gene-environment interaction—means biology is not destiny.

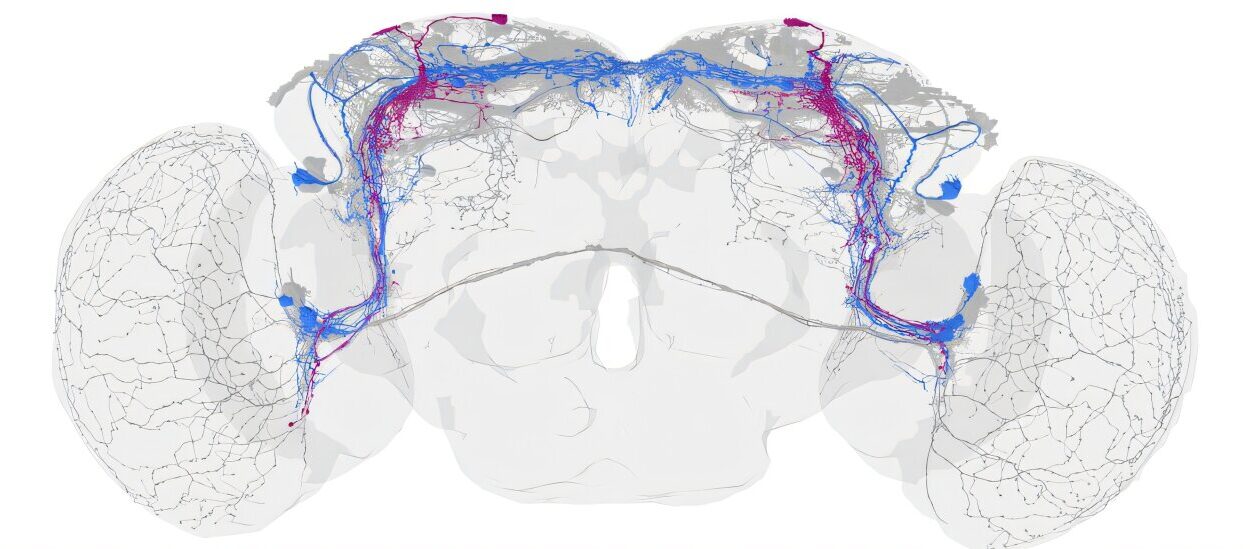

Neuroscientist Richard Davidson has shown that infants exhibit stable patterns of brain activity that correlate with personality traits later in life. Some show high activity in the left frontal lobe, linked to approach behaviors and positive emotion. Others show higher activity in the right frontal lobe, linked to withdrawal and fear.

These brain patterns aren’t fixed, but they provide clues: we may start with a temperament that leans introverted or extroverted, cautious or bold—but life reshapes the brain, too.

Neurotransmitters: The Brain’s Chemical Code for Personality

If the brain is a city of electrical circuits, neurotransmitters are the messages sent across its networks. These chemicals—dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and others—do more than move thoughts; they shape how we feel and behave.

Dopamine is the “reward” chemical. It fuels motivation, pleasure, and the drive to pursue goals. People with higher baseline dopamine activity may be more curious, risk-seeking, and extroverted. Studies link dopamine receptor genes to traits like novelty-seeking and sociability.

Serotonin, on the other hand, helps regulate mood and impulse control. Low levels are associated with depression, anxiety, and aggression. Some antidepressants work by boosting serotonin availability, subtly shifting mood and behavior over time.

Oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” plays a key role in bonding, trust, and social connection. Released during hugs, childbirth, and even eye contact, oxytocin levels can influence how open or guarded we feel with others. In animal studies, voles given oxytocin become more monogamous and nurturing.

While we cannot reduce personality to just brain chemicals, they provide powerful insights into why some people seem wired for intensity, warmth, suspicion, or resilience.

Personality Disorders and the Fragility of Identity

Not all personality traits fall within what society calls “normal.” In some individuals, patterns of thought and behavior become so rigid, extreme, or maladaptive that they lead to diagnosis of personality disorders. These include borderline, antisocial, narcissistic, and schizotypal personality disorders, among others.

Brain imaging has revealed striking differences in people with these disorders. For instance, individuals with antisocial personality disorder often show reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, possibly underlying their lack of empathy and impulse control. Those with borderline personality disorder may have hypersensitive amygdalas and disrupted connectivity with emotion-regulating regions.

These findings challenge the notion of free will in troubling ways. If someone commits a crime due to a malformed brain circuit, are they fully responsible? The legal system is beginning to grapple with such questions, as neuroscience increasingly blurs the line between personality, choice, and pathology.

Yet it also offers hope. Therapy, medication, and neurofeedback can change patterns. Brains are plastic. Identity, though rooted in biology, is not written in stone.

Can Your Brain Type Predict Your Personality?

Some modern personality models attempt to classify people based on brain structure. The famous Big Five personality traits—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—have been correlated with specific neural patterns.

Extraverts, for example, tend to have more responsive dopamine systems and larger medial orbitofrontal cortices, linked to reward. Conscientious people may show greater volume in the lateral prefrontal cortex, linked to planning. Neuroticism has been associated with heightened amygdala responses and stronger connections to the hippocampus, a memory-processing center.

New brain imaging techniques like diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) allow scientists to map the brain’s white matter connections, revealing how efficiently different regions communicate. Some researchers are now using machine learning to predict personality traits based on these neural fingerprints.

But such models are still in their infancy. While correlations exist, they are far from deterministic. No scan can yet predict your favorite color, deepest fear, or the way you laugh when you’re nervous. Personality is not a code to be cracked, but a story still being written.

Trauma, Healing, and the Brain’s Emotional Imprint

What happens when the brain is hurt—not by a rod, like Phineas Gage, but by life itself?

Trauma, especially in childhood, can leave lasting imprints on the brain. Abuse, neglect, or chronic stress can alter the size of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. Such changes can shape personality traits like mistrust, hyper-vigilance, or emotional numbing.

PTSD, for instance, is associated with overactive fear circuits and underactive executive function. Survivors may become withdrawn or aggressive, not because they choose to, but because their brains are trying to protect them.

The good news is that healing is possible. Therapy, meditation, social support, and even psychedelics (in controlled, clinical settings) are being shown to reshape brain circuits. The brain is not a fixed map—it’s a landscape in flux, capable of repair and rebirth.

As the poet Rumi once wrote, “The wound is the place where the Light enters you.” Neuroscience increasingly affirms this truth: personality is not just what happens to you, but how your brain responds—and recovers.

The Role of Culture, Language, and Belief

If brains shape personality, why do different cultures value such different traits? Western societies often prize independence, ambition, and extroversion. Eastern cultures may emphasize humility, harmony, and restraint.

Research shows that cultural values can influence not only behavior but brain function. For example, East Asian participants tend to show more activity in brain areas associated with context and group identity when making judgments, whereas Westerners show more activation in self-referential areas.

Language, too, shapes thought. Bilingual people often report feeling like different “selves” depending on which language they speak. Beliefs, rituals, and family dynamics—all of which exist outside the brain—loop back to sculpt the brain’s internal wiring.

So while biology lays the foundation, personality is a cultural dance. The brain listens to the world, adapts to it, and slowly, like a sculpture taking form, carves the person we become.

Free Will, the Self, and the Ultimate Question

If personality is influenced by brain chemistry, structure, genetics, and environment, do we have any freedom at all? Are we just puppets pulled by invisible strings?

This is not merely philosophical—it’s deeply personal. If your brain makes your decisions, what part of you is truly “you”?

Some neuroscientists argue that free will is an illusion—that we’re consciousness passengers, narrating choices after our brain has made them. Others believe consciousness plays a real, active role in shaping thought.

Perhaps the truth lies in between. Just as we can train a muscle, we can shape brain patterns through intentional practice. Meditation can increase prefrontal control. Learning can rewire circuits. Trauma can be healed. Patterns can be broken.

The self, then, is not a static entity, but a dynamic process—an ongoing dialogue between biology and will, nature and nurture, past and possibility.

The Wonder of It All

In the end, asking whether personality is “all in your head” is a bit like asking whether music is all in the strings of a violin. Yes, the strings vibrate. But the music also lives in the hands that play it, the ears that hear it, the room that echoes with it.

Your personality is shaped by the folds of your cortex and the flow of neurotransmitters. But it also lives in your stories, your scars, your laughter, your loves. It is encoded in your brain, yes—but also in your relationships, your hopes, and the way you see the world.

Is it all in your head?

No. And yes. And far more than that.

The brain is not just an organ. It is a universe—one that holds not only thoughts and memories but the deepest mysteries of who we are. To study the brain is to study the soul through a microscope. And to know personality is to trace the contours of human possibility.

You are more than your brain. But your brain, wondrous and alive, is a part of your every smile, every sorrow, every leap of faith.

And that, perhaps, is the most human truth of all.