During the late Middle Pleistocene, a vast and untamed wilderness stretched across what is now the Kashmir Valley of South Asia. Between 300,000 and 400,000 years ago, a dramatic and enigmatic scene unfolded on the muddy banks of a river near present-day Pampore: the demise of at least three colossal elephant relatives, their bones soon blanketed by sediment and time. But these weren’t just any elephants—and their fate wasn’t just a matter of nature taking its course.

More than 80 stone tools were found alongside these ancient giants, pointing to a startling truth: early human ancestors had been here, and they had feasted.

Now, over two decades after the fossils were unearthed, a team of paleontologists led by Advait Jukar, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, has illuminated this prehistoric moment with new scientific insight. Their findings, recently published in Quaternary Science Reviews and the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, reveal the oldest known evidence of animal butchery in India—forever altering our understanding of early human life on the subcontinent.

Unearthing the Giants: Discovery of the Pampore Fossils

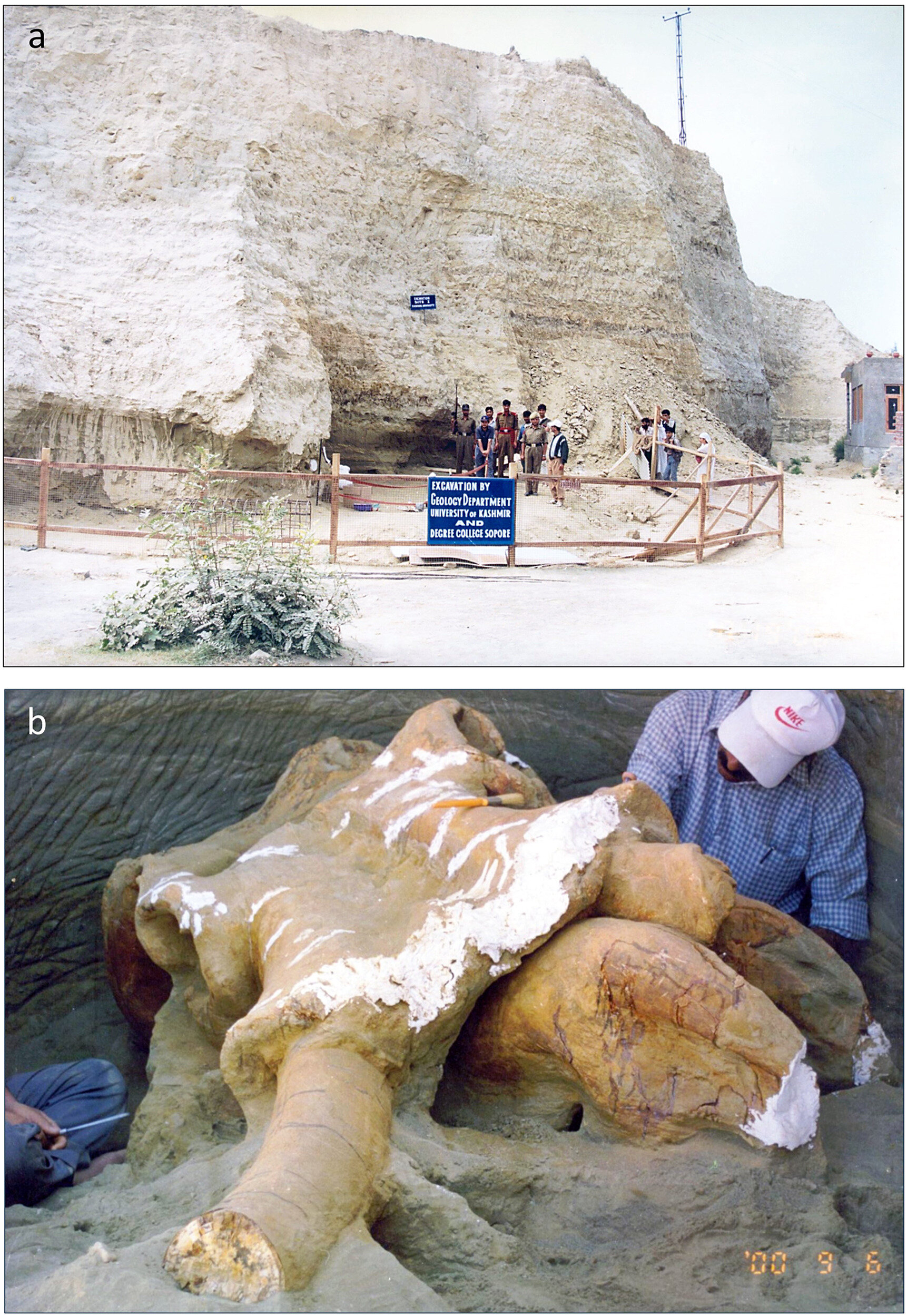

The story begins in 2000, when a fossil discovery near Pampore uncovered a remarkable graveyard: the remains of several massive elephants and a cache of stone tools. For years, the fossils sat in scientific limbo—fragmented, unclassified, and unexplained.

Only recently did researchers confirm that the bones belonged to Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus, a now-extinct elephant genus that once roamed Eurasia. These weren’t just any elephants: Palaeoloxodon species were enormous, some weighing over 20,000 pounds—more than twice the mass of today’s African elephants.

What made the Pampore site even more special was the quality and completeness of the fossils. A nearly intact skull, several large bones, and—most intriguingly—tools and signs of marrow extraction. These remains are not only among the most complete Palaeoloxodon fossils found in South Asia but also hold the key to a deeper mystery about the human past.

Butchery Before Agriculture: The Oldest Evidence in India

For decades, archaeologists have combed the Indian subcontinent in search of signs that prehistoric humans hunted or scavenged large animals. The evidence was scant, limited mostly to stone tools and a single fossil hominin: the enigmatic Narmada human discovered in 1982. But direct evidence of butchery? Until now, it simply didn’t exist.

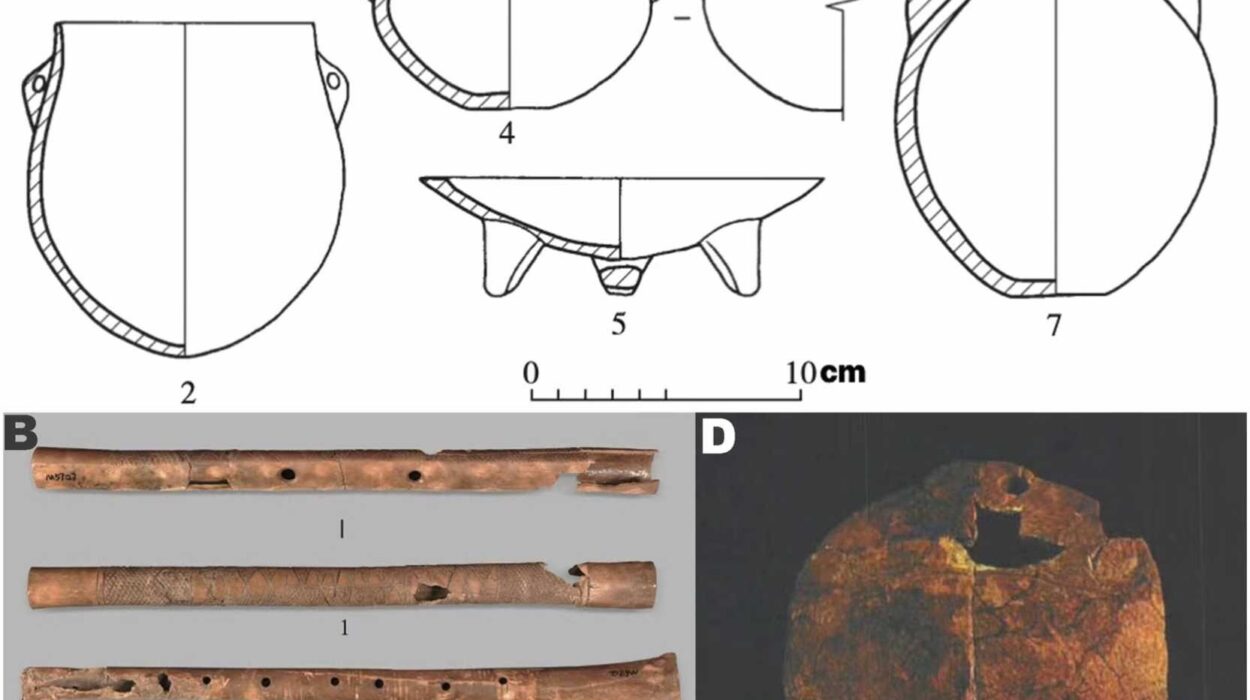

That changed when Jukar’s team identified bone flakes from the Pampore site—fractured fragments showing clear signs of percussion. These were no accidents of nature. Early humans had intentionally struck the bones to access marrow, a prized, fat-rich tissue that provided a crucial energy source.

This marks the earliest confirmed instance of large-animal butchery in India, predating previous evidence by hundreds of thousands of years. And it’s a groundbreaking shift in our understanding of early human behavior on the subcontinent.

“Now we know for sure,” Jukar explained, “at least in the Kashmir Valley, these hominins were eating elephants.”

Tools from Afar: Clues to Prehistoric Movement and Planning

Alongside the elephant bones were 87 stone tools—scrapers, flakes, and chopping implements. But these weren’t fashioned from local stone. They were made of basalt, a volcanic rock not native to the immediate Pampore region. This suggests that early hominins transported raw materials from elsewhere before shaping them at the site, perhaps planning in advance for a large-scale butchery operation.

The tools themselves were dated to between 300,000 and 400,000 years ago based on construction methods and stratigraphic context. This period falls within the late Middle Pleistocene, a transformative era for hominin evolution. Populations of Homo heidelbergensis, Homo erectus, and other archaic humans moved across Africa and Eurasia, setting the stage for the rise of Homo sapiens.

Death of a Giant: Illness, Scavenging, or the Hunt?

One question lingers: Did early humans hunt this massive Palaeoloxodon, or did they merely scavenge an already-dead animal?

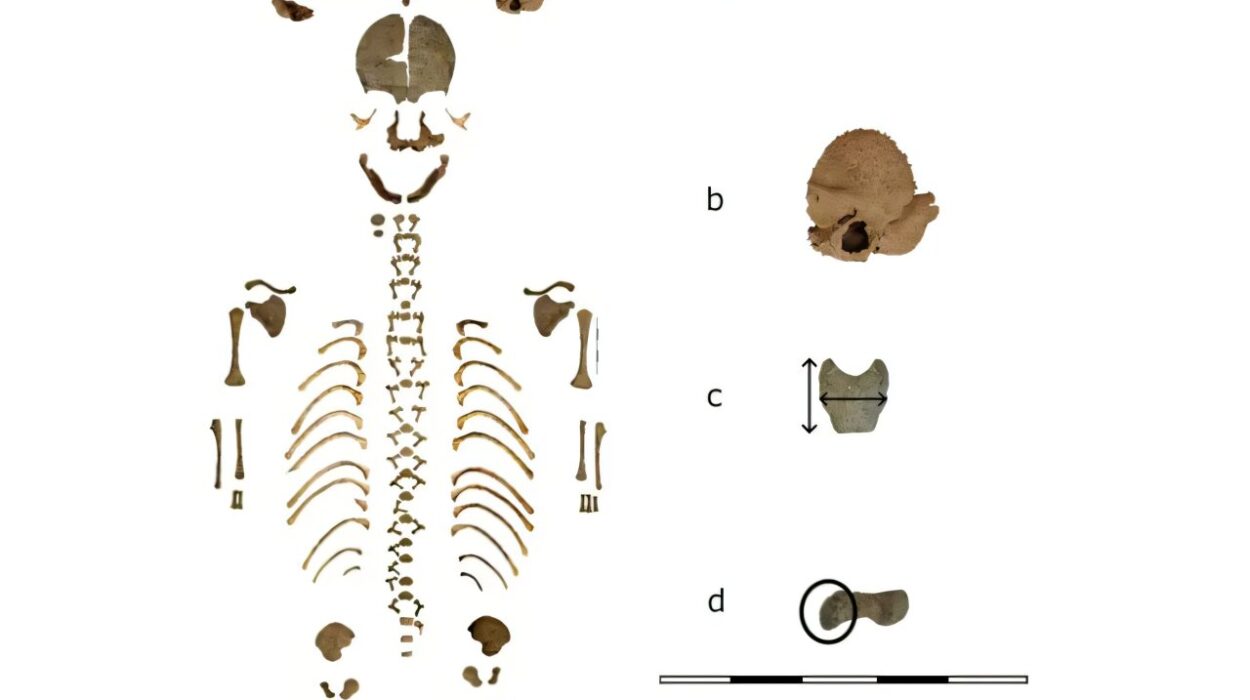

The researchers found no embedded spear points or direct signs of weapon-inflicted trauma. However, the skull of the largest specimen—belonging to a mature male—revealed abnormal bone growth inside the sinus cavities. This pathology likely resulted from a chronic sinus infection, weakening the animal and possibly contributing to its death.

Jukar posits that the elephant may have died of natural causes, perhaps getting mired in the soft sediment along the Jhelum River. Such an entrapment would have offered a rare feast to nearby hominins.

This ambiguity speaks to a broader challenge in paleoanthropology: distinguishing hunting from scavenging. But the stone tools and marrow extraction marks make one thing clear—regardless of how the elephant died, early humans took full advantage of its remains.

A Rare Species: Tracing the Evolution of Palaeoloxodon

Until now, only one fossil of Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus had ever been found—a partial skull fragment discovered in Turkmenistan in 1955. But it was incomplete, limiting what scientists could say about this unusual elephant.

The Pampore skull changes that. It is not only the most complete P. turkmenicus specimen ever found, but it also provides crucial anatomical details—especially of the hyoid bones, delicate structures at the base of the tongue that are rarely preserved.

These hyoids, along with the elephant’s partially developed forehead bulge, show that P. turkmenicus represents an intermediate stage in Palaeoloxodon evolution. Unlike their later descendants, which sported massive domed skulls, P. turkmenicus displayed a gentler expansion of the frontal bone, linking African origins to Eurasian diversification.

“It shows this kind of intermediate stage in Palaeoloxodon evolution,” said Jukar. “The specimen could help paleontologists fill in the story of how the genus migrated and evolved.”

India’s Role in the Human Journey

While Africa has long been celebrated as the cradle of humanity, the Indian subcontinent is increasingly recognized as a crucial corridor for early human migration. The Pampore discoveries reinforce this narrative.

To date, only one hominin fossil—again, the Narmada human—has been found in India. Its anatomical features suggest a blend of archaic and modern traits, indicating that India was home to diverse hominin populations moving in and out of Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia.

But evidence like that found at Pampore adds behavioral context. These people weren’t just passing through; they were living, adapting, and exploiting the resources around them—including the largest land mammals of the Pleistocene.

A Call for Renewed Exploration

For Jukar, the Pampore site is a reminder that many more stories are waiting to be uncovered beneath the soil of South Asia.

“The thing I’ve come to realize after many years,” he said, “is that you just need a lot more effort to go and find the sites, and you need to essentially survey and collect everything.”

In the past, fossil collectors focused on perfect skulls or intact bones, overlooking the shattered, seemingly insignificant fragments. But as this study shows, those fragments may hold the most revealing clues—traces of ancient tools, signs of butchery, and evidence of a meal that once fed a hungry band of hominins.

A Glimpse into Prehistoric Life

The discoveries at Pampore don’t just reveal an elephant’s death or a tool’s sharp edge—they pull back the curtain on a vibrant, dangerous world where early humans walked the land with megafauna, crafting tools from distant stone and exploiting whatever nature offered.

They tell us that India, far from being a blank space on the paleoanthropological map, was a dynamic arena of human activity and innovation long before written history began.

And as scientists return to the field with new eyes and better methods, the ghosts of the past—giant elephants, skilled toolmakers, and early scavengers—may yet reveal more secrets from the sediments of time.

References: Ghulam M. Bhat et al, Human exploitation of a straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon) in Middle Pleistocene deposits at Pampore, Kashmir, India, Quaternary Science Reviews (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108894

Advait M. Jukar et al, A remarkable Palaeoloxodon (Mammalia, Proboscidea) skull from the intermontane Kashmir Valley, India, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2024). DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2024.2396821