Social engagement is more than just casual conversation or catching up with friends—it’s a powerful contributor to overall health. From heart health to mental resilience, being socially connected has long been tied to a longer, healthier life. Yet, as people age, many find themselves becoming more withdrawn, less interested in social interaction, or simply less able to maintain it. Until recently, this decline in sociability was often chalked up to external factors like retirement, physical limitations, or bereavement. But compelling new research out of Singapore is reshaping that narrative by exploring how changes deep within the brain itself may drive these behavioral shifts.

A new study from Nanyang Technological University in Singapore offers a biological explanation for why sociability seems to wane with age. The research suggests that changes in the brain’s intrinsic functional connectivity—not just life circumstances—may be the underlying force behind the shrinking social circles many older adults experience.

What Is Sociability and Why Does It Matter?

Sociability is a psychological trait encompassing a person’s ability to effectively communicate, regulate emotions, and assert themselves in social contexts. It’s a multi-dimensional skill set that supports forming and maintaining relationships, adapting to social environments, and even enjoying the simple pleasure of human interaction. For most people, sociability helps regulate stress, promote positive mental states, and reinforce a sense of identity and belonging.

But sociability doesn’t remain static across the lifespan. As people age, a consistent trend emerges: they become less socially engaged. Whether by choice, circumstance, or unseen neurobiological shifts, older adults, especially those living alone, often experience increasing isolation. Reduced social interaction is not merely a lifestyle change—it poses serious risks to mental and physical health, including cognitive decline, depression, and even mortality.

A Bold New Hypothesis: It’s All in Your Brain

The researchers behind the study titled “Intrinsic functional connectivity brain networks mediate effect of age on sociability”, published in PLOS One, sought to explore a less visible but profoundly impactful component of aging: brain connectivity. Using advanced neuroimaging techniques, they investigated whether shifts in how different regions of the brain communicate could explain the decline in sociability.

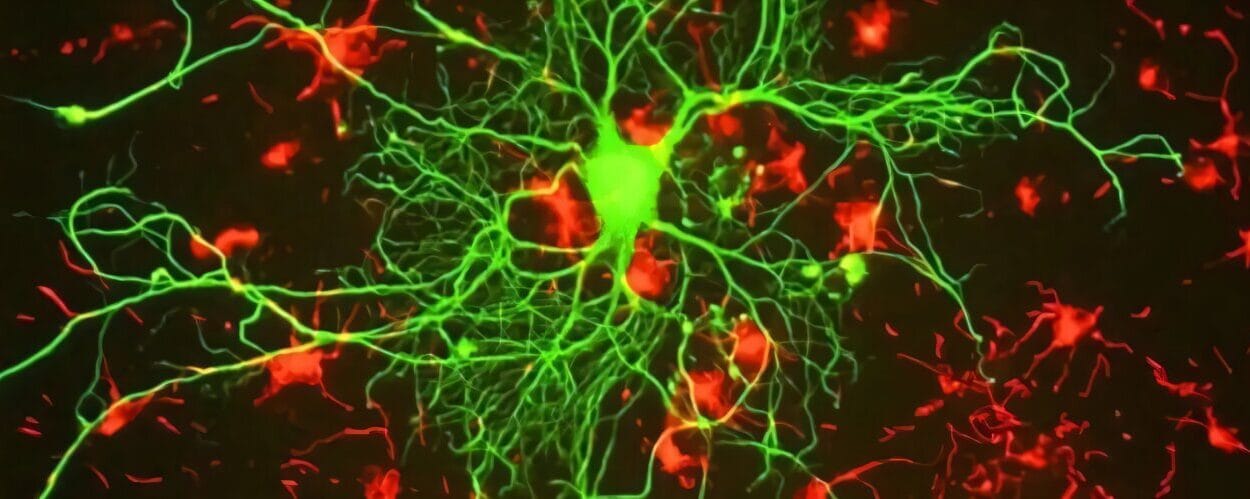

To do this, they utilized data from the Leipzig Study for Mind-Body-Emotion Interactions, which included 196 healthy adults between the ages of 20 and 77. Participants completed the Sociability subscale of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire—a validated self-report measure of one’s perceived sociability. They also underwent resting-state fMRI scans, which measure the brain’s activity when a person is not engaged in a specific task. This “resting” activity is rich with information about the brain’s intrinsic functional connectivity—essentially, how different parts of the brain remain in sync even during downtime.

The Brain’s Changing Communication Landscape

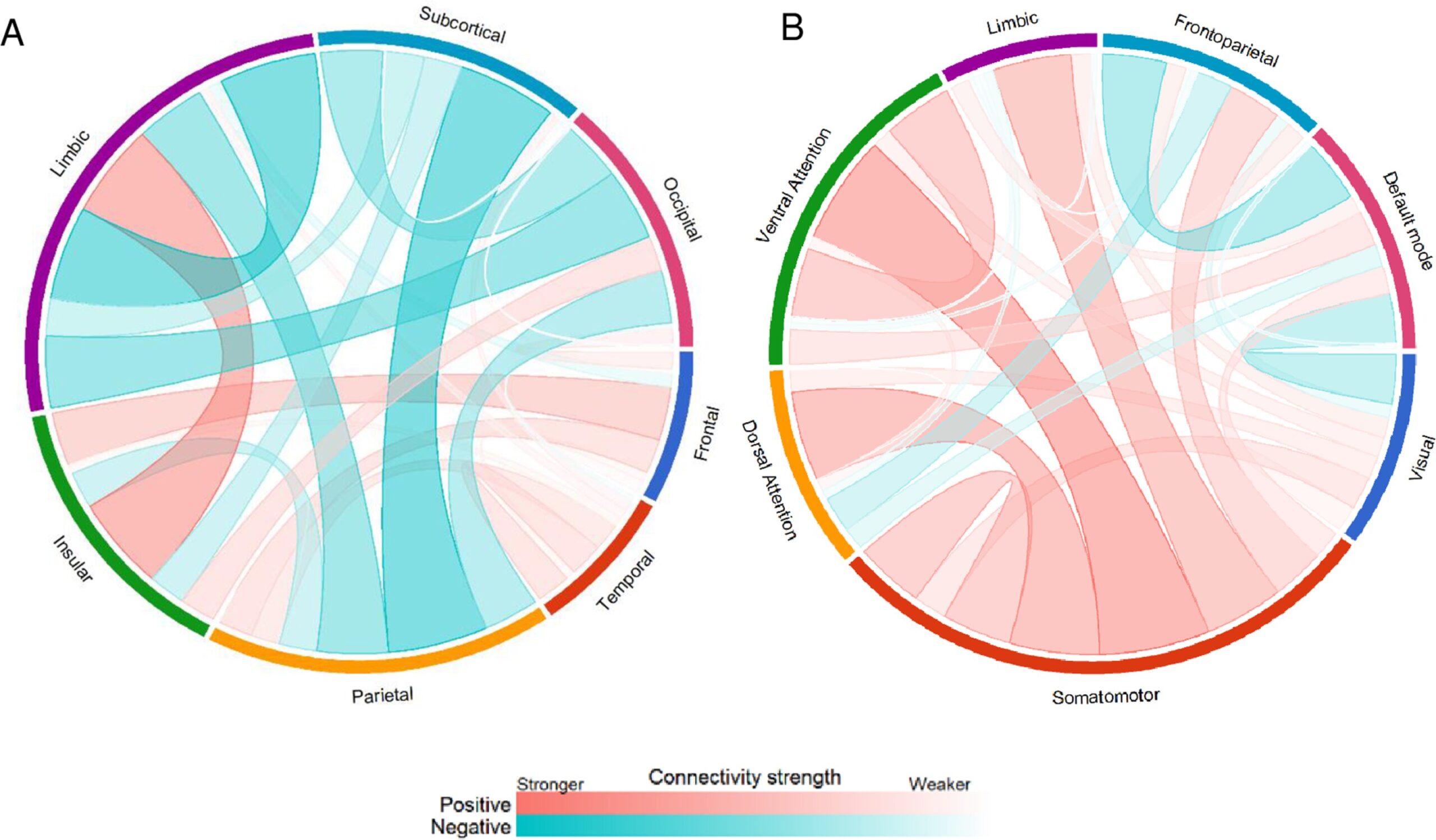

The researchers applied network-based analytical techniques to identify patterns of functional connectivity that varied with age. They discovered two distinct neural networks with opposite behaviors across the lifespan, each correlated with sociability.

The first, named the Age-Positive Network (APN), exhibited increased connectivity with age. Ironically, while this might sound beneficial at first, stronger connectivity in the APN was actually associated with lower sociability. This network was largely composed of limbic-insular and ventral attention–somatomotor connections—regions involved in emotion processing, bodily awareness, and attention redirection. The increasing connectivity here may reflect a kind of neural overintegration, where emotion and sensorimotor systems dominate cognitive control, potentially disrupting the subtle social cues and nuanced emotional regulation that sociability demands.

The second network, known as the Age-Negative Network (ANN), showed decreased connectivity as people aged. This weakening of connectivity was also linked to reduced sociability. The ANN comprised areas like the frontoparietal control network, the default mode network (DMN), and connections between subcortical and parietal regions. These networks are central to social cognition, introspection, memory, and executive function. When their connectivity weakens, a person’s ability to plan social interactions, interpret others’ emotions, and manage socially complex situations may falter.

Two Networks, One Decline

Here’s where it gets fascinating: mediation analysis revealed that these two networks independently and completely mediated the relationship between aging and sociability. In other words, the entire decline in sociability with age can be explained by these specific changes in brain network connectivity. The strengthening of the APN and the weakening of the ANN occur in parallel, each driving sociability downward through different mechanisms.

This dual-network transformation represents a kind of neural reorganization. Rather than operating as clearly defined, efficient systems, the brain’s networks may become less specialized and more entangled with age—a process known as functional network desegregation. In simpler terms, the brain loses some of its compartmentalization. The precise, coordinated functioning needed for complex social interaction becomes muddied, which may lead to reduced emotion regulation, lower confidence, and diminished communicative fluency.

Social Decline as a Neurobiological Norm

This research reinforces a powerful idea: declining sociability in older adults is not just circumstantial—it may be a neurobiologically grounded component of aging. The findings align with Robin Dunbar’s social brain hypothesis, which posits that human social structures and capacities are tightly linked to the evolution of large and complex brains. As our brains age, the systems that support rich social interaction begin to falter. What might seem like a change in personality could, in fact, be a reflection of changes in brain wiring.

Recognizing this internal dimension of sociability loss is crucial. It challenges the stigma that sometimes surrounds older adults who become less socially engaged, reframing their behavior not as apathy or stubbornness, but as the result of biological changes. Understanding the neuroscience behind aging and social behavior can also inform how we support older populations—not by blaming or pressuring them to “be more social,” but by creating structures and interventions that align with their evolving neurological reality.

Implications for Health, Policy, and Interventions

These findings open the door to a variety of practical applications. Public health strategies could incorporate psychoeducation to inform older adults and caregivers about the normal, brain-based shifts that affect sociability. By understanding that decreased sociability is not necessarily a symptom of depression or cognitive failure—but rather a part of normative brain aging—individuals can respond with greater empathy, insight, and adaptability.

Moreover, programs aimed at sustaining sociability might benefit from focusing less on forcing social exposure and more on training the specific cognitive and emotional skills that underlie social interaction. For instance, interventions could target emotion regulation, attentional control, and memory through cognitive exercises, mindfulness, or structured group activities. Technology-assisted tools like virtual reality or adaptive AI companions might also play a role in helping older adults maintain emotional and cognitive engagement in a more accessible, pressure-free environment.

The study also reinforces the need for preventive care earlier in life. Since the connectivity changes that lead to sociability decline start gradually, building cognitive reserve through lifelong learning, social engagement, and emotional development might help buffer the effects of neural desegregation.

Redefining Aging in a Social Context

This research challenges the narrative that aging is solely a physical process or that social withdrawal is always pathological. Instead, it presents aging as a dynamic, systemic transformation where brain function shifts in ways that directly affect how we engage with the world. In doing so, it invites a broader, more compassionate perspective on aging—one that integrates the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of life.

Understanding that changes in sociability may stem from underlying neural transitions doesn’t make the experience of isolation any less real or serious. However, it does provide a powerful tool: awareness. With this knowledge, communities can design better environments for aging—ones that accommodate brain-based changes with respect and creativity, rather than resistance or shame.

Conclusion: From Insight to Action

The decline in sociability with age, long viewed as a side-effect of circumstance, is now being illuminated as a deeply neurobiological process. Thanks to the study from Nanyang Technological University, we now understand that aging brains don’t just slow down—they rewire in ways that affect how we interact, emote, and connect.

Rather than viewing these changes as deficits, we can begin to see them as natural shifts that, with the right support and understanding, can be navigated. By integrating neuroscience with social policy, caregiver training, and individual psychoeducation, we can create a society where aging minds remain socially engaged in ways that are meaningful and attainable.

In a world where human connection is more vital than ever, understanding how the brain influences our sociability may be the key to fostering healthier, more connected lives—regardless of age.

Reference: Yuet Ruh Dan et al, Intrinsic functional connectivity brain networks mediate effect of age on sociability, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324277