In the human imagination, intelligence has long been our domain. We build cities, launch rockets, craft poetry, and ponder the origin of the universe. But as science has peered deeper into the natural world, it has revealed a humbling truth: we are not alone in our brilliance. The planet teems with minds—alien, silent, and profoundly intelligent—that do not speak in words or write equations but nonetheless understand, innovate, and feel.

From the eerie click-language of dolphins to the problem-solving skills of crows, from the social strategies of elephants to the cooperative complexity of ants, the animal kingdom pulses with brains capable of feats that once seemed uniquely human. What defines intelligence in this diverse landscape is not a singular measure like an IQ score but a kaleidoscope of capabilities: memory, planning, empathy, language, innovation.

To understand animal intelligence is not simply to marvel at it. It is to confront deep questions about consciousness, evolution, and even our own humanity. Intelligence, as it turns out, is not a mountain with us at the summit. It is a sprawling forest, full of paths and secrets, and other creatures have been walking it far longer than we realized.

The Evolutionary Puzzle of Animal Intelligence

Intelligence does not arise by accident. It evolves when it gives creatures an edge—survival, reproduction, adaptation. In the vast tree of life, different branches have developed mental abilities suited to their ecological needs. Intelligence is not a one-size-fits-all concept. It is deeply shaped by environment and lifestyle.

Predators often need tactical thinking. Social animals must understand cooperation and competition. Long-lived species require memory. Animals that use tools or language show foresight and innovation. Intelligence, then, is not linear—it is ecological, tailored to life’s challenges.

For example, the octopus evolved high intelligence in the absence of a backbone, in an underwater world where camouflage, manipulation, and curiosity were survival tools. Primates developed theirs in the dense social mazes of troop life, where alliances, empathy, and deception could mean the difference between power and exile.

This diversity tells us something profound: intelligence is not bound by biology. It can arise in feathers or fur, in neurons that fire in very different ways, across vastly different evolutionary timelines. Nature has not just one way of being smart. It has many.

Dolphins: Masters of the Deep

Beneath the waves, a different kind of genius swims in silence. Dolphins are not just playful performers at marine parks; they are the brilliant navigators of an invisible world. With brains larger than ours relative to body size, they live in complex social groups, use names to identify each other, and pass on cultural behaviors.

Dolphins communicate with clicks, whistles, and body movements. These sounds are not random—they carry information, perhaps even abstract concepts. Some scientists believe dolphins use a form of language, complete with syntax and possibly even grammar, though much remains to be decoded.

What’s even more astonishing is their self-awareness. In mirror tests, dolphins recognize themselves, a sign of consciousness rare in the animal kingdom. They display empathy, mourning the loss of pod members, and even rescue injured humans or fellow dolphins.

Their intelligence appears to be both social and spatial. Navigating three-dimensional ocean environments using echolocation requires extraordinary cognitive mapping. In captive environments, dolphins understand symbols, solve puzzles, and cooperate with humans in sophisticated ways.

To know a dolphin is to glimpse a mind shaped not by fire and stone, like ours, but by sound and sea. Their intelligence whispers that there are other ways of being brilliant—other minds, other models.

Elephants: The Gentle Giants of Memory and Mourning

If elephants appear wise, it’s because they are. These colossal beings are not just marvels of size but marvels of sentience. Their brains, weighing over five kilograms, are the largest among land animals. But it’s not size alone that matters—it’s structure. The elephant’s brain is built for emotion, memory, and social complexity.

Elephants remember. They remember water holes across decades and deserts. They remember the faces and voices of humans. They remember friends, enemies, and those they’ve lost. Scientists have documented elephants returning to the bones of deceased relatives, gently touching skulls and tusks in apparent mourning.

Their social lives are rich and layered. Matriarchs lead family groups with wisdom honed by years. Younger elephants learn from older ones, adopting customs passed down across generations. This transmission of culture—of learned behaviors—is a sign of deep cognitive function.

In times of distress, elephants comfort one another. They have been seen exhibiting post-traumatic behaviors after witnessing the death of companions or destruction of their habitats. Their empathy stretches across species. There are documented cases of elephants helping injured zebras, dogs, even humans.

To observe an elephant grieve is to feel something ancient and powerful—an echo of our own humanity reflected in another form. Their minds remind us that intelligence is not just knowing but feeling.

Crows and Ravens: The Feathered Intellects

If you’ve ever been outwitted by a bird, it was probably a crow. Members of the corvid family, including crows, ravens, and magpies, exhibit intelligence that rivals primates. With brains the size of walnuts, they perform feats that suggest abstract reasoning, planning, and even a sense of humor.

Crows make and use tools—a rarity in the animal world. They shape sticks into hooks, bend wires to reach food, and solve multi-step puzzles that require foresight and experimentation. Some species, like the New Caledonian crow, pass these skills down through generations, creating cultural lines of technological innovation.

These birds also remember human faces. If you wrong a crow, it will remember you—and may tell its friends. If you help one, it may return the favor, gifting shiny objects in return. Their ability to hold grudges and alliances is eerily human.

In urban environments, crows exploit traffic lights to crack nuts. In the wild, ravens play games, sliding down snowy hills for fun or teasing other animals. Play is often a sign of cognitive richness, a brain not just surviving but enjoying its world.

What makes corvids remarkable is not just their problem-solving but their awareness. They show signs of metacognition—thinking about their thinking. Some experiments suggest they can anticipate what others know or see. In their feathered forms, a kind of mind unfolds that forces us to rethink what birds can be.

Great Apes: Our Reflective Kin

Among all animals, none are as closely tied to our own cognitive lineage as the great apes. Chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans are not just our relatives in genetics—they are kin in thought. They gesture, learn language, use tools, and even reflect on their pasts.

Chimpanzees hunt in coordinated teams, form political coalitions, and engage in acts of deception. They learn sign language and understand symbols. They console one another after conflict, express joy, and grieve the dead. Bonobos, known for their peaceful societies, exhibit empathy and sexual behaviors that mirror human complexity.

Orangutans, the forest-dwelling giants of Southeast Asia, build sleeping nests each night, use sticks to extract insects, and have been observed crafting umbrellas from leaves. Their solitary nature belies a deep intelligence expressed in careful planning and adaptability.

Gorillas display understanding of fairness, language, and play. The famous gorilla Koko learned hundreds of signs and formed emotional bonds with her caregivers, once mourning the loss of a kitten as deeply as a human child might.

What sets great apes apart is not just tool use or memory, but the ability to engage in reflection. They recognize themselves in mirrors, indicating a sense of self. They show theory of mind—awareness that others have beliefs and desires separate from their own.

In them, we glimpse ourselves not as rulers of a separate world, but as branches of the same tree—differently shaped, but rooted in shared evolutionary soil.

Cephalopods: The Minds with Tentacles

Perhaps the strangest intelligence on Earth lives under the sea, not in a vertebrate, but in a mollusk. Octopuses, squids, and cuttlefish belong to the cephalopods—a group whose minds evolved completely separately from our own. Yet their cognitive abilities are staggering.

Octopuses can open jars, escape complex enclosures, and remember solutions to puzzles. They display personalities—some shy, some bold. They play with toys, observe humans, and mimic other sea creatures. All this despite having a nervous system that is partly decentralized: much of their brain is distributed through their arms.

Each arm can function semi-independently, learning and reacting without waiting for orders from the central brain. This distributed intelligence is unlike anything in the vertebrate world. It’s as if the octopus is many minds in one body.

Cephalopods use camouflage not only for hiding but for communication. Their skin can change color and texture in milliseconds, broadcasting emotion or signaling intentions. Some species even flash rhythmic light patterns to court mates or warn enemies.

Given their short lifespans—most octopuses live only a few years—their intelligence is even more remarkable. Unlike primates who have decades to learn, these creatures develop complex cognition in a fraction of the time.

Their minds, shaped by a completely different evolutionary path, suggest that intelligence is not the rare outcome of a single lineage—it may be a recurring solution to the challenges of life.

Dogs and the Intelligence of Companionship

Human civilization owes much to one animal more than any other: the dog. For tens of thousands of years, dogs have lived alongside us, adapting to our behaviors, responding to our emotions, and even anticipating our needs. Their intelligence is not just about problem-solving—it is deeply social.

Dogs understand human gestures better than chimpanzees. They can follow a pointed finger, respond to tone of voice, and learn hundreds of words. Some border collies, like the famous Chaser, have learned over a thousand object names and can fetch them on command.

But their genius lies in emotional resonance. Dogs read our faces, detect our moods, and mirror our feelings. They comfort us in grief, guard us in danger, and celebrate with us in joy. They have evolved not only to understand us but to care about us.

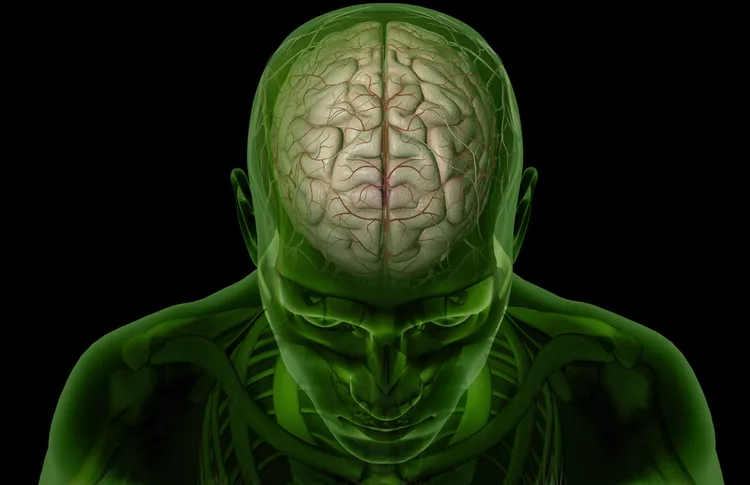

Recent studies show that dogs process language in the left hemisphere of their brains—just like humans. They also show signs of fairness, loyalty, and empathy. This emotional intelligence makes them not just companions, but partners in a deep cognitive bond.

Their closeness to humans has shaped their minds in profound ways. In dogs, we see intelligence shaped by relationship—not just the need to survive, but the desire to connect.

The Intelligence We Overlook

Amidst the headlines about apes and dolphins, there are quieter minds we often ignore. Pigs, for example, are capable of playing video games, solving mazes, and learning abstract concepts. Rats demonstrate empathy, freeing trapped companions. Parrots understand categories and can use words in context.

Even bees and ants, with tiny brains, exhibit remarkable intelligence. Bees communicate with dances, navigate complex routes, and learn by observation. Ants build societies with division of labor, farming, and even rudimentary medical care.

These creatures remind us that intelligence does not require a large brain. It requires the right brain, in the right context. They force us to redefine what it means to be smart.

The Mirror of Other Minds

To study animal intelligence is not just to catalog behaviors—it is to look into mirrors of consciousness that reflect parts of ourselves. It is to confront the unsettling, beautiful possibility that minds as rich and complex as ours exist in forms we once thought lesser.

They teach us that intelligence is not the privilege of language, nor the product of schooling. It is the ability to feel, to adapt, to imagine, to connect. It is not limited by species or size, but flows across evolution like a current—shaping, rising, transforming.

Our failure to recognize this has consequences. Animals suffer when we deny their inner lives. Conservation, captivity, and even pet ownership must reckon with the reality that these beings are not automata—they are aware, responsive, feeling.

As we continue to explore the minds of animals, we are also exploring the edges of our own identity. What makes a mind? What is consciousness? What responsibilities come with intelligence?

A World Alive with Thought

The Earth is not merely populated by creatures—it is filled with thinkers. They swim beneath waves, swing through forests, fly over cities, and curl up at our feet. Their thoughts are not like ours, but they are no less real.

To see the world this way is to walk more gently upon it. To treat every animal not as an object of curiosity but as a fellow traveler in the long, mysterious journey of consciousness.

In every gaze—from the dolphin’s eye to the raven’s stare to the elephant’s tear—there is a story, a spark, a knowing. In recognizing their minds, we deepen our own.

And perhaps, in the end, that is what intelligence truly is: not just solving problems or remembering facts, but understanding that we are not alone. That the world is more alive, more feeling, more brilliant than we ever imagined.