In the familiar world of matter, something has never quite added up. Protons and neutrons, the sturdy anchors of every atom, are made from quarks bound together by gluons. Yet the mass of these particles is far larger than the tiny quarks inside them. It is as if nature is hiding a secret beneath the surface, offering only a vague hint that “the numbers don’t add up,” and inviting physicists into one of the universe’s deepest puzzles.

For decades, researchers believed the Higgs mechanism could provide the answer. After all, it gives elementary particles their bare mass—a fact triumphantly confirmed by experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider and crowned by the 2013 Nobel Prize for Peter Higgs. But when physicists looked closely at protons and neutrons, they found that the Higgs contributed “less than 2%” to their masses. The rest seemed to come from nowhere at all.

“This clearly demonstrates that the dominant part of the mass of real-world matter is generated through another mechanism, not through the Higgs,” said Victor Mokeev of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Jefferson Lab. “The rest arises from emergent phenomena.”

That missing mass—most of the mass of everything we see, touch, and are—has now become the focus of one of the most ambitious scientific quests of our time.

The Rise of an Invisible Mechanism

To understand where this mass originates, physicists turned to quantum chromodynamics, or QCD, the theory describing how quarks and gluons interact through the strong force. QCD suggests that the mass of protons and other hadrons emerges from the intense energy stored within these interactions. This phenomenon has a name: emergence of hadron mass, or EHM.

A decade-long global effort has begun revealing the outlines of this process. The breakthrough comes from a QCD-based approach called the continuum Schwinger method, or CSM. By studying how the strong interaction changes with distance or momentum, scientists are now gaining clarity on the dynamic forces that give matter its heft.

The effort stretches across nearly thirty years of experimental results collected at Jefferson Lab. As researchers carefully analyzed this treasure trove of data, they found themselves standing at the edge of a new understanding of the mass-generating process.

“This is more than what you’d see from a single experiment or set of experiments,” said Jefferson Lab physicist Daniel Carman. “This is the payoff from what we’ve been doing at Jefferson Lab for decades. We still have a lot of work ahead, but this marks a major milestone along the way.”

A Universe Built from Gluon Fire

The strong force, carried by gluons, has a remarkable property: gluons interact with one another. Most forces in nature do not behave this way, and Mokeev highlighted how transformative this special feature is. “Without gluon self-interaction, the universe would be completely different,” he said. “It creates beauty through different particle properties and makes real-world hadron phenomena through emergent physics.”

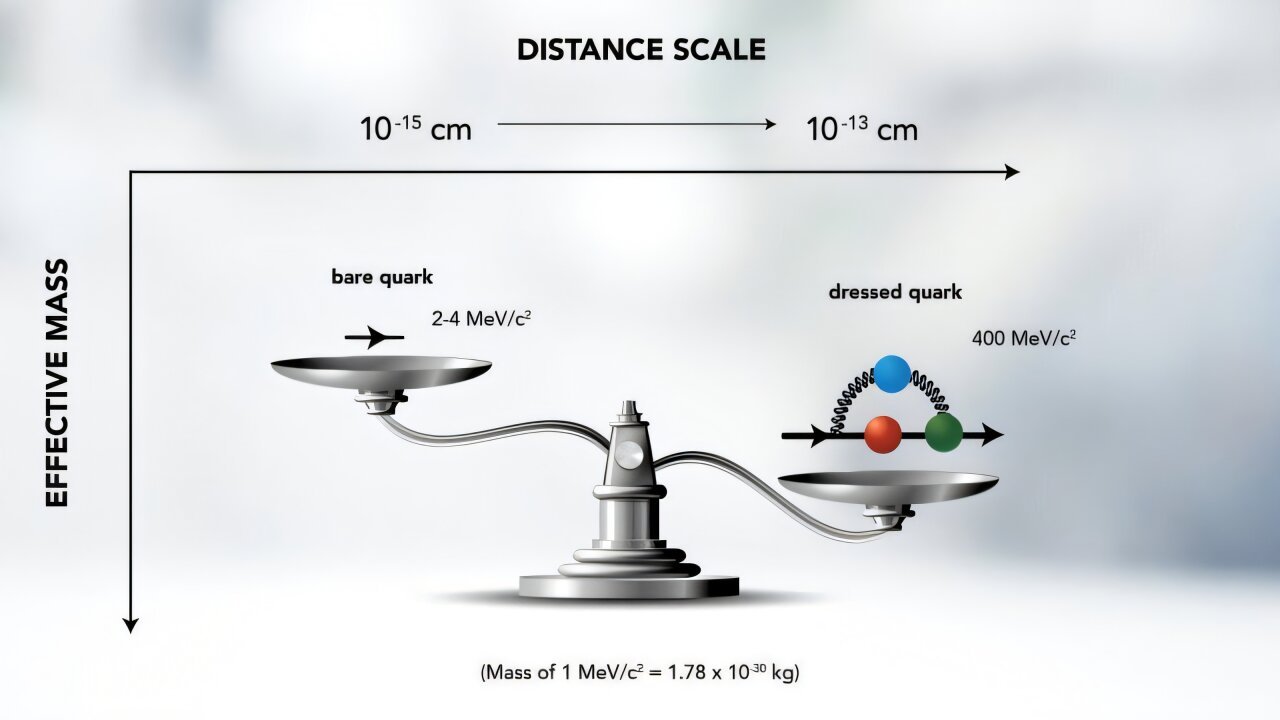

At extremely small distances, around the size of a proton, the building blocks of matter begin to change character. Bare quarks and gluons—the ones described in fundamental QCD—become “dressed.” They surround themselves with clouds of strongly coupled quarks and gluons that continuously burst into and out of existence. In this environment, the masses of quarks grow dramatically, rising from nearly weightless to about 400 MeV.

This transformation is the engine of EHM. Three of these dressed quarks combine under the strong force to form a proton weighing roughly 1 GeV. Its excited-state cousins populate the range between 1.0 and 3.0 GeV. This mass does not exist in the quarks themselves but emerges from the energy and dynamics of the strong interaction.

The question now is whether scientists can map how these dressed-quark masses evolve using real experimental data. Jefferson Lab is pushing toward that answer.

Inside the Showdown of Theory and Experiment

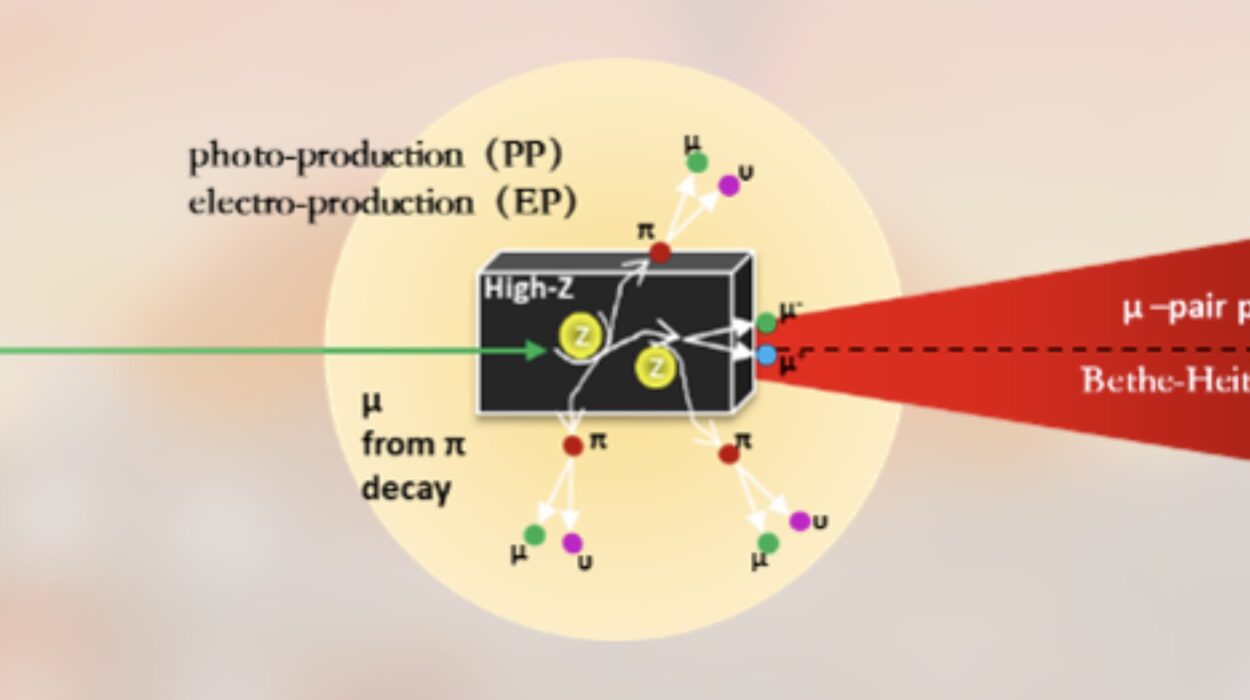

The heart of this effort lies in the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility—CEBAF—one of the most powerful electron beam machines in the world. Inside Jefferson Lab’s Experimental Hall B stands the towering CLAS12 detector, three stories high and built to track particles from nearly every possible angle.

CLAS12 and its predecessor, CLAS, have spent decades bombarding protons with high-energy electrons. Each collision cracks open a momentary glimpse into the structure of protons and their excited states. These snapshots allow scientists to measure how quarks and gluons behave at different distances. The results can then be directly compared with CSM predictions to test the EHM framework.

The comparison has become strikingly clear. Experiments show that dynamically generated, dressed-quark masses are indeed the active components shaping the proton and its excited states. The match between CSM predictions and Jefferson Lab’s data indicates that EHM is not just a theoretical concept but a real physical process detectable in the laboratory.

“This kind of work requires synergy between experiment, phenomenology, and theory,” Carman said. “You need all of these different contributors working together in close collaboration to get at the physics we’re trying to uncover.”

Toward a Complete Map of Mass

Although these findings mark a breakthrough, the journey is far from over. Mokeev echoed this sentiment clearly: “We see much more work ahead.”

Experiments conducted during the earlier 6 GeV era of CEBAF investigated the distance range responsible for roughly 30% of hadron mass. The upgraded 12 GeV program is now extending that reach to about 50%. But the dominant portion of hadronic mass emerges beyond that, and scientists are already dreaming of future machines with even higher energy.

“When we get this information from the data of future experiments, we will be able to map out the full range of distances where the dominant part of hadron mass and structure emerge,” Mokeev said.

The horizon is clear: the full picture of mass—what it is, how it forms, and why it fills the universe—is within reach.

Why This Quest Matters

The emergence of mass is one of the most fundamental questions humans can ask. Everything we see around us, from mountains to planets to our own bodies, is built from particles whose masses come not from the Higgs mechanism, as once believed, but from the deep, churning dynamics of QCD. Understanding this process means understanding the true origin of almost all visible matter.

The Jefferson Lab studies, bridging decades of experiments and innovative theory, are bringing clarity to a mystery that has long stood at the core of physics. They show that mass is not simply given—it emerges from the restless dance of quarks and gluons, governed by a force that becomes stronger the closer it pulls things together. By mapping this process, scientists are uncovering the hidden engine of the universe.

The story of mass is the story of how the universe became solid, structured, and alive. And with each new insight, we come one step closer to understanding how our world gains the weight of reality itself.

More information: Patrick Achenbach et al, Electroexcitation of Nucleon Resonances and Emergence of Hadron Mass, Symmetry (2025). DOI: 10.3390/sym17071106. www.mdpi.com/2073-8994/17/7/1106