The story of Antarctica’s melting ice shelves often feels like a slow and distant drama, measured in decades or centuries. But a team of researchers from the University of California, Irvine and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has discovered something far more urgent happening beneath the frozen surface: storms. Not the storms we see raging across the sky, but swirling, turbulent “ocean storms” born in the deep water that carve into the ice from below with startling speed.

Their new study, published in Nature Geoscience, reveals that these fast-moving, stormlike circulation patterns are not rare. They are constant, powerful, and capable of triggering sudden bursts of melting under some of the most vulnerable ice shelves on the planet. And the closer scientists looked, the more dramatic the story became.

A New Way of Seeing Time in the Ice

Until now, most research into Antarctic melting focused on broad seasonal or annual patterns. But the team behind this study suspected that the story was unfolding on a much shorter timescale. To test this idea, they zoomed in not on months, but on days, tracking how small but energetic patches of swirling water—known as submesoscales—slipped beneath the ice.

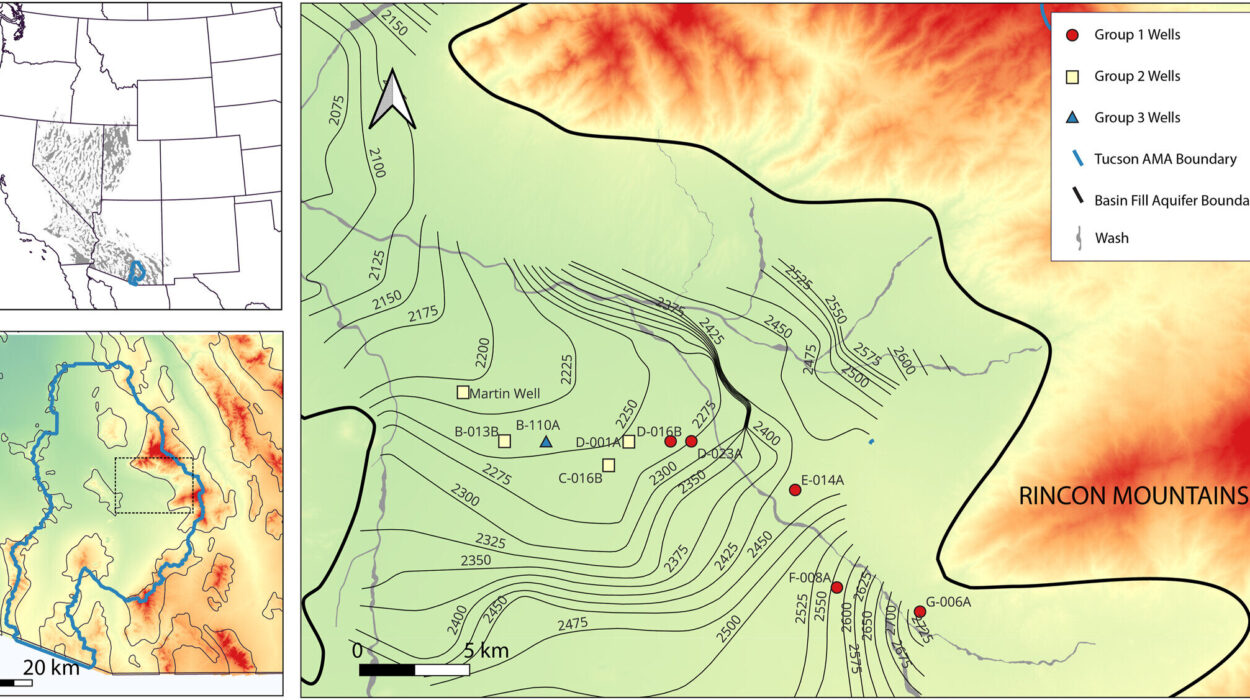

The scientists combined climate simulation models with moored instruments anchored deep in the Amundsen Sea Embayment, home to the troubled Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers. Their tools captured the ocean with astonishing clarity, resolving features just a few kilometers across in a region dominated by enormous slabs of floating ice.

With this high-resolution view, the researchers began to spot patterns that had gone unnoticed. These submesoscale features behaved like storms at sea, but their impact unfolded in a world of darkness beneath ice hundreds of meters thick.

Storms in the Deep

Lead author Mattia Poinelli describes these dynamics in terms that bridge land and sea. “In the same way hurricanes and other large storms threaten vulnerable coastal regions around the world, submesoscale features in the open ocean propagate toward ice shelves to cause substantial damage,” he said. These ocean storms draw warm water upward and into hidden cavities under the ice shelves. The result is melting—sudden, aggressive, and far more intense than scientists previously realized.

“Submesoscales cause warm water to intrude into cavities beneath the ice, melting them from below. The processes are ubiquitous year-round in the Amundsen Sea Embayment and represent a key contributor to submarine melting.”

As the team studied these events, they uncovered a feedback loop that made the story even more dramatic. When the storms strike, melting accelerates. And that melting, in turn, fuels more turbulence in the water. Poinelli explained it clearly: “Submesoscale activity within the ice cavity serves both as a cause and a consequence of submarine melting.”

This cycle intensifies the storms themselves. The meltwater becomes unstable, sharpening the boundaries between water layers and strengthening the ocean features that first triggered the melting. Those intensified features then pump even more heat upward, accelerating the damage. It is a self-reinforcing pattern that can transform a calm sub-ice environment into something violently dynamic.

When Minutes and Hours Matter

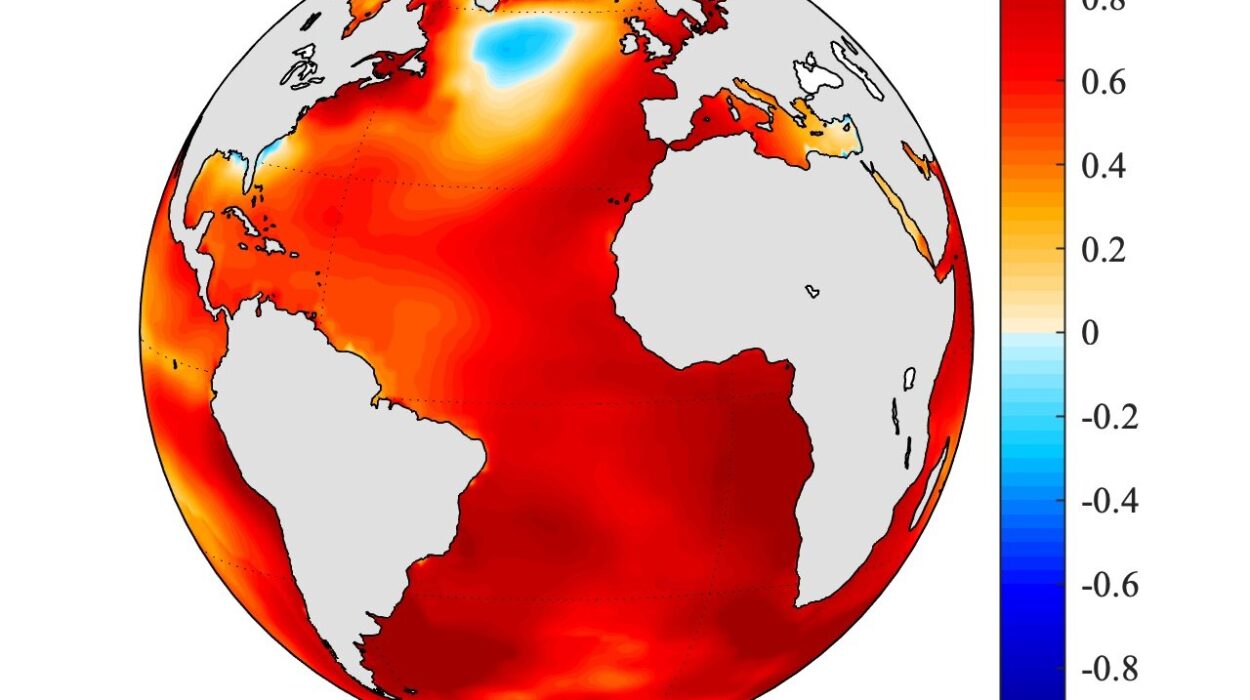

One of the most striking discoveries is the speed of these melting events. The researchers found that these high-frequency processes explain nearly a fifth of all variations in melting over a full seasonal cycle. But during extreme collisions between submesoscale storms and the ice front, melting can spike to triple its normal rate within just hours.

Such events are short-lived, but their impact is profound. High-resolution observational data from moorings and floats echo what the models show: sudden bursts of warmth and salinity at depth, matching the magnitude and timescales of the extreme melting. Each event is like a flash flood of heat against the ice.

Poinelli pointed to one particularly vulnerable region: “The region between the Crosson and Thwaites ice shelves is a submesoscale hot spot.” The floating tongue of Thwaites and the shallow seafloor beneath it act as a kind of storm trap, amplifying the turbulence and making the area even more susceptible.

What the Future Could Bring

The implications of these findings stretch far beyond individual melting events. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet holds enough water to raise global sea levels by up to three meters if it collapses. The new research suggests that the future climate may create even more favorable conditions for submesoscale activity.

Warmer ocean waters, longer periods of open water known as polynyas, and reduced sea ice coverage could all boost the formation of these energetic fronts. With more storms rushing beneath the ice shelves, instability could grow, pushing the region closer to tipping points scientists fear.

The study offers a vision of Antarctica not as a static landscape but as a place alive with hidden, fast-moving forces—forces that respond quickly to a warming world.

Why the World Should Pay Attention

Mattia Poinelli emphasized the significance of these discoveries for the global scientific community. “These findings demonstrate that fine oceanic features at the submesoscale—despite being largely overlooked in the context of ice-ocean interactions—are among the primary drivers of ice loss,” he said. He stressed that these short-lived, “weatherlike” ocean processes must be included in future climate models if we hope to project sea level rise with greater accuracy.

Eric Rignot, who advised the early-career team, underscored the need for action: “This study and its findings highlight the urgent need to fund and develop better observation tools, including advanced oceangoing robots that are capable of measuring suboceanic processes and associated dynamics.”

The message that emerges is clear and sobering. Antarctica’s vulnerability is shaped not only by vast currents and long-term warming, but also by the small, fast, violent storms racing through the deep. Understanding these storms is no longer a scientific curiosity. It is essential for preparing for a future where the ocean, the ice, and the world’s coastlines are increasingly intertwined.

More information: Ocean submesoscales as drivers of submarine melting within Antarctic ice cavities, Nature Geoscience (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-025-01831-z.