The Arctic seems like an unlikely place to find the remains of an ancient tropical sea, yet beneath the cold winds and jagged peaks of Spitsbergen lies a story that stretches across deep time. It is a story of disaster and rebirth, of oceans emptied and oceans revived, and of creatures that returned to the water long before dinosaurs ruled the land.

More than 30,000 teeth, bones, scales, and fossils from a thriving 249-million-year-old marine community have been uncovered on this remote island, part of Norway’s Svalbard archipelago. These discoveries preserve a vanished world from the early Triassic period — a time just after Earth’s greatest catastrophe, when life stood on the brink of permanent collapse. What the fossils reveal is surprising, almost shocking: life bounced back far faster, and far more explosively, than scientists ever expected.

The fossil trove is the result of nearly a decade of painstaking excavation, preparation, and analysis. It comes from an international team of Scandinavian paleontologists at the University of Oslo’s Natural History Museum and the Swedish Museum of Natural History, whose findings now appear in the journal Science. Their work does more than describe extinct creatures — it challenges one of the longest-standing ideas in paleontology about how Earth recovered from the biggest mass extinction in history.

A Window into the Ocean of a Reborn World

Spitsbergen is already famous among paleontologists. Its mountains hold rock layers formed on the floor of the Triassic seas, once located at middle to high latitudes along the edge of the vast Panthalassa super-ocean. These rocks have produced iconic fossils for decades: early ichthyosaurs, strange amphibians, and other marine predators that represent the first land-dwelling animals to fully adapt to life far from shore.

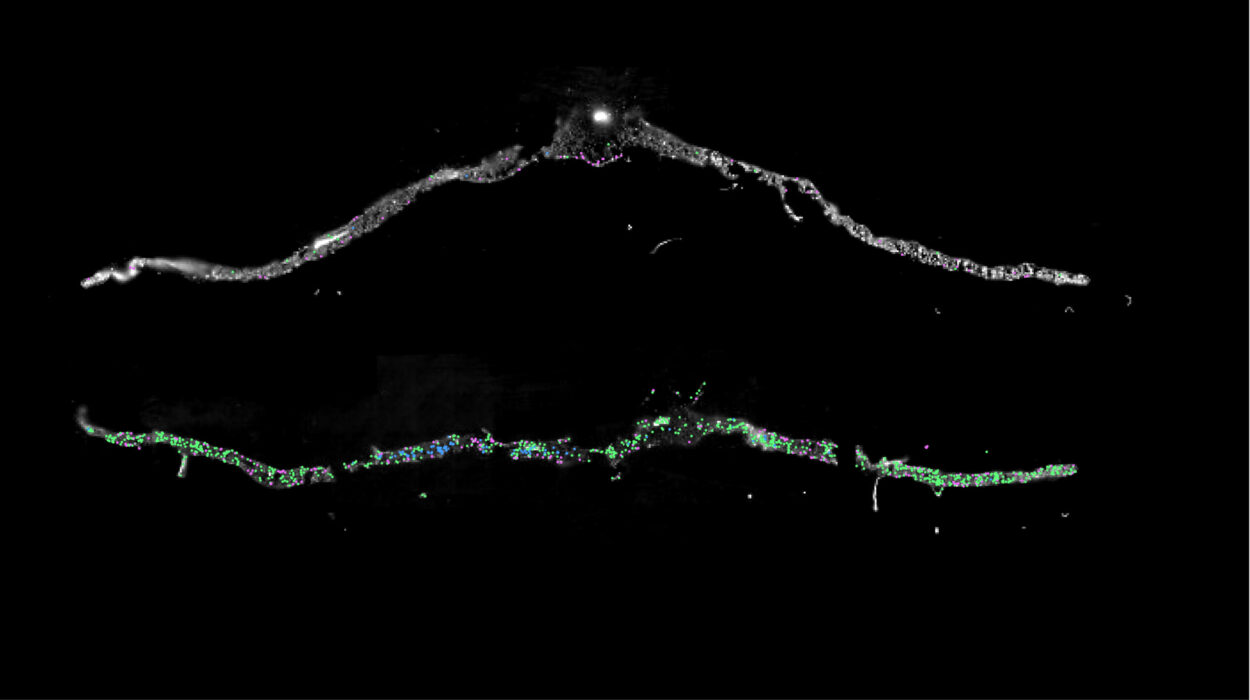

Yet the newly described deposit is different. It is not a scattered collection of isolated finds. It is a dense, continuous bonebed — a layer so packed with material that it visibly weathers out of the mountainside. Tiny fish scales lie beside shark teeth, next to reptile bones the size of a human arm. The sheer abundance suggests a bustling ecosystem, a complex pyramid of predators and prey, frozen in time.

Stratigraphic dating places this bonebed at around 249 million years old. That timing is crucial because it situates the ecosystem only about three million years after the devastating end-Permian mass extinction event — the “Great Dying” that wiped out over 90% of marine species and reshaped Earth’s biosphere forever.

For decades, scientists believed that life recovered slowly, gingerly, hesitatingly. The prevailing model suggested that it took eight million years or more for marine reptiles and amphibians to colonize open ocean environments again. According to that view, oceans remained impoverished and unstable for a long stretch of time after the extinction.

But the fossils from Spitsbergen tell a different story.

Life Rebound Faster Than Anyone Imagined

The painstaking excavation of the site involved mapping and collecting fossils from 1-square-meter grids across a 36-square-meter area. More than 800 kilograms of fossil material were collected — a massive undertaking that required years of preparation work. Among the finds were coprolites (fossilized feces), tiny bone fragments, large vertebrae, delicate shark teeth, and pieces of skulls from massive marine reptiles.

Together, these remains paint a vivid picture of a flourishing, complex ecosystem. Predatory reptiles and amphibians dominated the oceans, suggesting that food chains had already rebuilt themselves into sophisticated networks. Ichthyosaurs — the famous “fish-lizards” — were already diverse and fully aquatic. Some were small, nimble hunters chasing squid-sized prey; others were enormous apex predators exceeding five meters in length.

There were archosauromorphs too, distant relatives of modern crocodiles, adapted to long-distance swimming. Their presence points to a lineage far more ancient and resilient than previously believed. The diversity within the bonebed is extraordinary — one of the richest marine vertebrate assemblages ever found from this time period.

The implications are profound. Marine life did not simply recover after the Great Dying — it surged back with surprising speed. The oceans, once devastated, re-established thriving communities in just a few million years.

Rethinking the Aftermath of Earth’s Greatest Mass Extinction

The end-Permian extinction event, 252 million years ago, was the most catastrophic in Earth’s history. Fueled by immense volcanic eruptions during the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea, the planet was plunged into a nightmare of hyper-greenhouse conditions. Oceans turned acidic, oxygen levels collapsed, and land temperatures soared. More than nine out of ten marine species vanished.

For decades, textbooks and research papers described the aftermath as slow and painful. The recovery model suggested stepwise colonization of the oceans: first amphibians, then primitive reptiles, and later more specialized marine predators. This gradual timeline seemed logical given the scale of the disaster.

But the new Spitsbergen bonebed overturns this narrative. Instead of a hesitant resurgence, the fossils point to a burst of evolutionary activity. Marine reptiles and amphibians didn’t wait millions of years to adapt — they were already present, diverse, and widespread only three million years after the extinction. Some evolutionary lineages appear to predate the extinction itself, suggesting that the transition from land to water began earlier than anyone had suspected.

This implies that life’s resilience was far stronger than assumed. The collapse of ecosystems did not permanently cripple evolution; instead, it opened ecological niches that surviving species rapidly filled. Predators reappeared. Food webs re-established themselves. Entire groups of marine reptiles began their radiation into offshore environments.

A Birthplace for Modern Marine Ecosystems

The Triassic oceans were the cradle of modern marine life. Many of the ecological strategies seen in today’s seas — fast-swimming predators, deep-water hunters, large migratory species, schooling fish — trace their origins to this recovery period. The Spitsbergen fossils capture the moment when these strategies were first experimenting with form and function.

The diversity of ichthyosaurs in the bonebed, ranging from small agile swimmers to giants, hints at rapid specialization. Archosauromorphs adapted for aquatic life show that the transition from land to sea occurred in multiple lineages simultaneously. Amphibians continued to thrive in marine settings longer than once thought. And the presence of sharks, bony fish, and a variety of small organisms shows that ecosystems were stable enough to support higher predators.

A global comparative analysis included in the study reveals that the Spitsbergen assemblage is one of the most species-rich marine vertebrate communities ever identified from the early Triassic. The findings also suggest that the evolutionary roots of marine reptiles reach back into the Permian, before the extinction unfolded, hinting at a more complex origin story for these groups.

These early ecosystems, reborn from disaster, laid the foundations for the rich marine communities we see today.

The Emotional Weight of Deep Time

There is something profoundly human about staring at a fossil from a world that existed almost 250 million years ago. These bones belonged to creatures that swam in sunlit Triassic waters when Spitsbergen was part of a warm coastal sea. They lived, hunted, reproduced, and died long before mammals or birds ever existed. Their world was ravaged, rebuilt, and reshaped through unimaginable forces.

Yet despite that devastation, life returned. Not slowly or tentatively, but with a fierce determination that seems almost biological in its urgency. The Spitsbergen fossils remind us that extinction, while tragic, is not always the end. Life adapts. Life evolves. Life finds a way back.

In a time when modern ecosystems face rising temperatures, ocean acidification, and unprecedented environmental pressures, the Triassic story carries both warning and hope. It shows the fragility of the world — but also the extraordinary resilience of living systems.

More information: Aubrey J. Roberts, Earliest oceanic tetrapod ecosystem reveals rapid complexification of Triassic marine communities, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adx7390. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adx7390