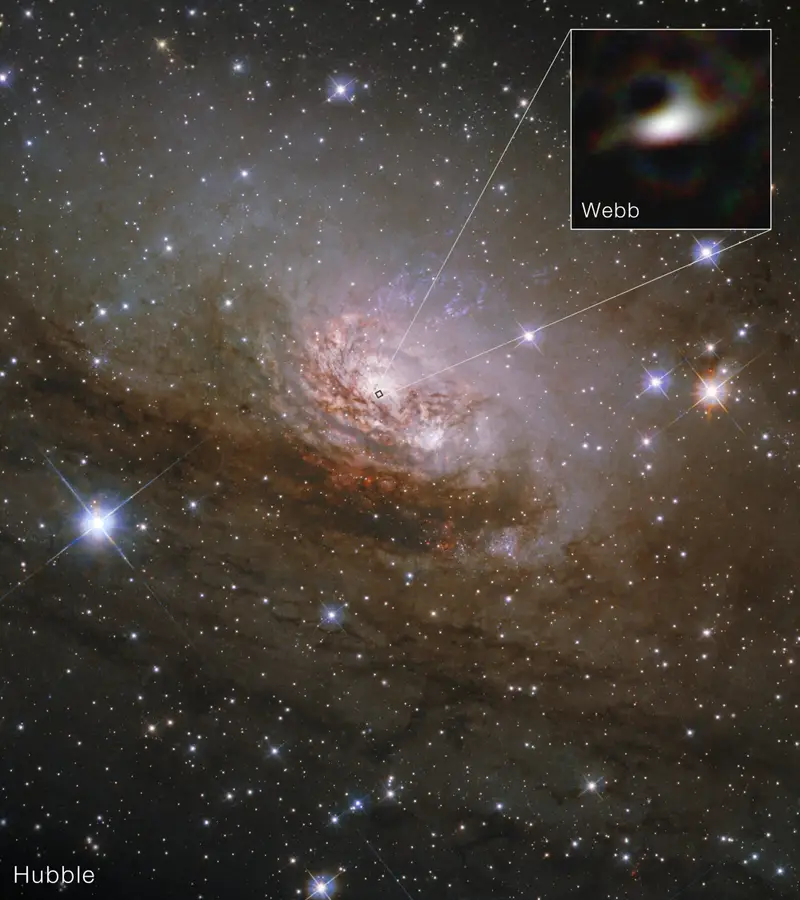

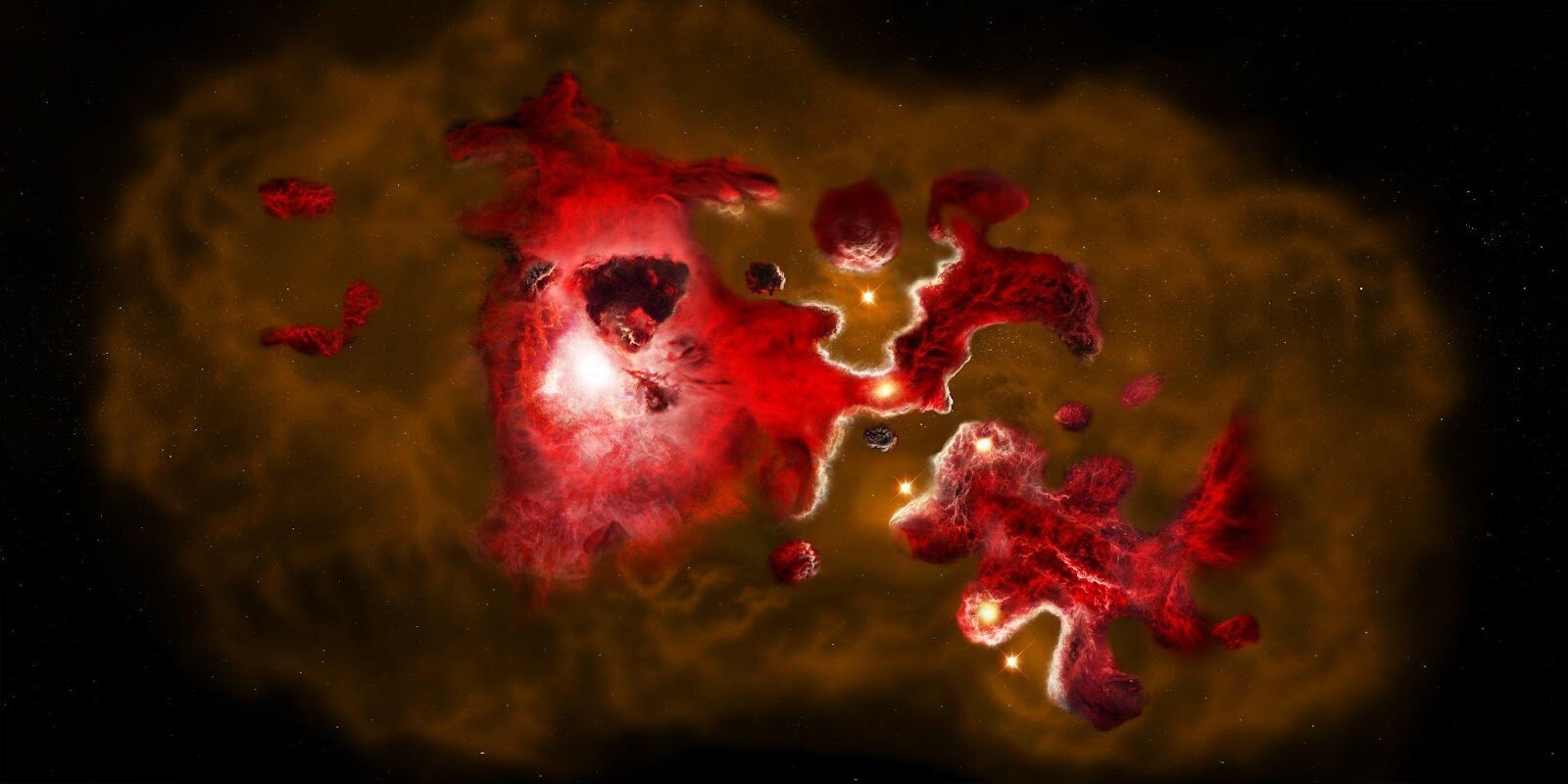

Thirteen million light-years away, the Circinus galaxy appears calm and unassuming. But deep in its core, hidden behind dense curtains of gas, dust, and starlight, a supermassive black hole is actively shaping the galaxy’s fate. For decades, astronomers believed they understood where the intense infrared light near this black hole came from. The brightest glow, they thought, was produced by violent outflows, streams of superheated material blasting away from the black hole’s center.

Now, that story has changed.

Using the unprecedented power of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, scientists have uncovered evidence that turns this long-standing idea on its head. The glowing dust is not fleeing the black hole. It is falling inward, feeding it.

The Long Shadow of an Invisible Giant

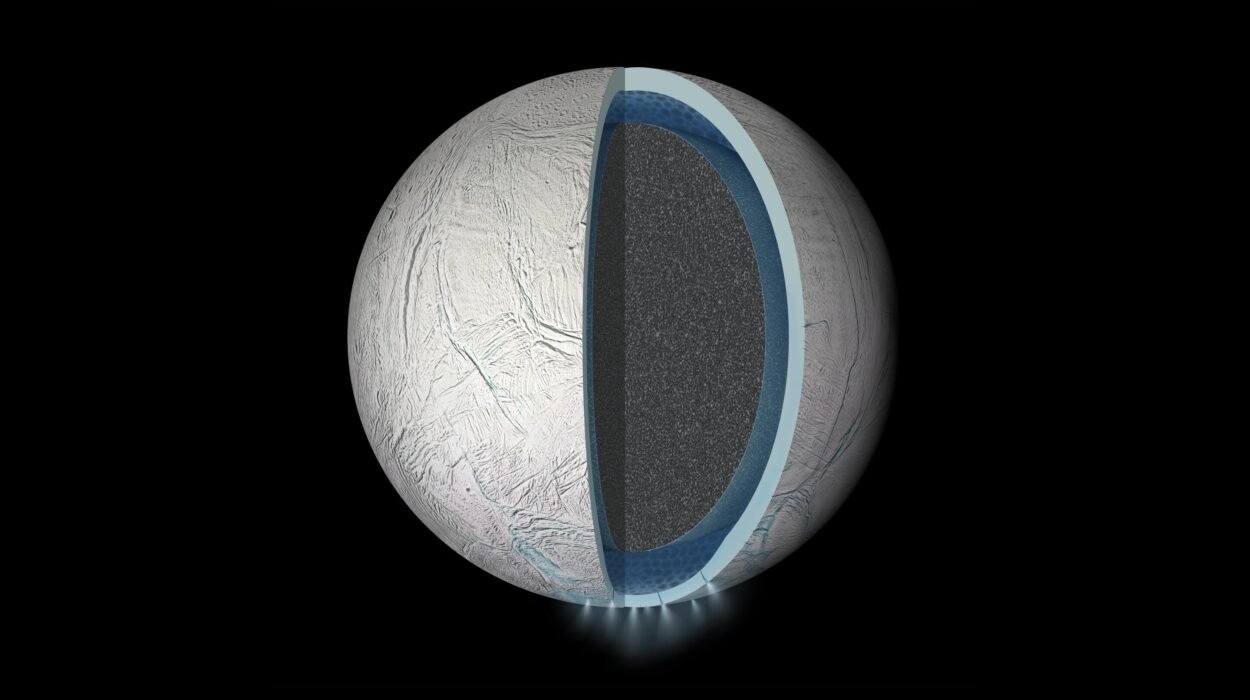

Supermassive black holes like the one in Circinus stay active by pulling in nearby matter. Gas and dust spiral inward, forming a thick, donut-shaped structure called a torus around the black hole. From the torus’s inner edge, material drifts closer, flattening into an accretion disk that whirls like water circling a drain.

As this disk tightens its spiral, friction heats the material until it begins to shine. That glow is powerful, but it comes from a region so compact and so deeply buried that astronomers have struggled to see it clearly. Bright starlight from Circinus itself overwhelms the view, and the torus blocks the innermost regions from direct observation.

For years, scientists had to rely on indirect clues. They gathered light across many wavelengths, blended together from different parts of the galaxy’s core, and tried to untangle it using theoretical models.

“In order to study the supermassive black hole, despite being unable to resolve it, they had to obtain the total intensity of the inner region of the galaxy over a large wavelength range and then feed that data into models,” said Enrique Lopez-Rodriguez, the study’s lead author from the University of South Carolina.

Those models were clever, but incomplete. They could match emissions from specific components, such as the torus, the accretion disk, or the outflows, but never all of them at once.

An Infrared Mystery That Wouldn’t Go Away

One puzzle refused to disappear. Some telescopes detected a surplus of infrared emissions from hot dust near the centers of active galaxies like Circinus. The light was clearly there, but its exact origin remained uncertain.

“Since the ’90s, it has not been possible to explain excess infrared emissions that come from hot dust at the cores of active galaxies,” Lopez-Rodriguez said. Existing models usually blamed either the torus or the outflows, but neither explanation fully worked.

Because the galaxy’s central region could not be resolved in detail, many models concluded that most of the mass and emission came from the outflows. The idea was compelling: powerful black holes blasting material outward, lighting it up as it escaped.

To truly test this theory, astronomers needed to do two things at once. They had to filter out the overwhelming starlight, and they had to separate the infrared glow of the torus from that of the outflows. For that, they needed Webb.

Turning Webb Into Many Telescopes at Once

Webb brought something entirely new to the challenge. To peer into Circinus, the team used the Aperture Masking Interferometer on Webb’s NIRISS instrument, an advanced mode that transforms the telescope itself into an interferometer.

On Earth, interferometers are often arrays of separate telescopes spread across large distances. By combining light waves from multiple collectors, they create interference patterns that reveal fine details otherwise impossible to see.

Webb achieves this effect on its own. A special mask containing seven small hexagonal holes is placed over the telescope’s aperture. Each hole acts as an individual light collector. As their light overlaps, it forms interference patterns that encode precise information about the source.

“These holes in the mask are transformed into small collectors of light that guide the light toward the detector of the camera and create an interference pattern,” explained Joel Sanchez-Bermudez of the National University of Mexico, a co-author of the study.

By carefully analyzing these patterns and cross-checking them with earlier observations, the team reconstructed an image of Circinus’s core with astonishing clarity. It became the first extragalactic observation from an infrared interferometer in space.

Seeing Twice as Sharp

The result was not just clearer, but sharper than anyone expected.

“By using an advanced imaging mode of the camera, we can effectively double its resolution over a smaller area of the sky,” Sanchez-Bermudez said. “Instead of Webb’s 6.5-meter diameter, it’s like we are observing this region with a 13-meter space telescope.”

For the first time, astronomers could distinguish where the infrared light was actually coming from. And what they saw was a surprise.

Rather than glowing outflows dominating the scene, the data showed that about 87% of the infrared emissions from hot dust originate from regions closest to the black hole itself. Less than 1% comes from hot dusty outflows. The remaining 12% arises from more distant regions that earlier instruments could not separate.

“It is the first time a high-contrast mode of Webb has been used to look at an extragalactic source,” said Julien Girard of the Space Telescope Science Institute, another co-author.

The excess infrared light that baffled astronomers for decades was not evidence of material escaping the black hole. It was a sign of matter being drawn in.

A Black Hole That Feeds, Not Flares

The findings paint a new picture of Circinus. Its black hole is not dominated by explosive outflows, but by steady accretion. The torus and inner disk are doing most of the glowing, quietly funneling material toward the center.

Lopez-Rodriguez noted that this fits Circinus’s character. “The intrinsic brightness of Circinus’ accretion disk is very moderate,” he said. “So it makes sense that the emissions are dominated by the torus.”

But this may not be true for all black holes. Brighter, more powerful systems could still be ruled by outflows, with energy and matter streaming outward instead of inward. Circinus may represent one point along a broader spectrum of black hole behavior.

Opening a Door to a Universe of Questions

Beyond solving one galaxy’s mystery, this work introduces a powerful new approach. Astronomers now have a tested technique for separating accretion and outflow emissions in nearby black holes, as long as the targets are bright enough for Webb’s interferometric mode.

“We hope our work inspires other astronomers to use the Aperture Masking Interferometer mode to study faint, but relatively small, dusty structures in the vicinity of any bright object,” Girard said.

The team envisions studying a dozen or two dozen black holes, building a statistical sample large enough to reveal patterns. By comparing systems of different luminosities, researchers can begin to understand how the balance between accretion disks and outflows relates to a black hole’s power.

“We need a statistical sample of black holes,” Lopez-Rodriguez said, “to understand how mass in their accretion disks and their outflows relate to their power.”

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it reshapes how astronomers interpret light from the hearts of galaxies. For years, excess infrared emissions were seen as signs of material being expelled. Now, at least in Circinus, they tell a different story, one of quiet consumption rather than dramatic escape.

By directly resolving regions once hidden behind dust and glare, Webb has shown that long-standing assumptions can be overturned with the right tools. Understanding whether black holes feed gently or blow material away is essential to understanding how galaxies evolve over cosmic time.

Circinus reminds us that even nearby galaxies can still surprise us. With Webb’s sharp new eyes, astronomers are no longer just guessing what happens in the shadows of black holes. They are finally watching the story unfold.

Study Details

Lopez-Rodriguez, E., et al. JWST interferometric imaging reveals the dusty torus obscuring the supermassive black hole of Circinus galaxy. Nature Communications (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66010-5 www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-66010-5