For many people, scars are not simply marks on the skin. They are constant reminders—etched into the body—of pain, trauma, and sometimes survival. While some scars fade into near invisibility, others remain stubbornly raised, rigid, and visibly distinct. Beyond the physical discomfort of tightness and restricted movement, scars can weigh heavily on self-image and mental health, shaping how people see themselves and how they believe others see them.

Despite decades of medical innovation, treatments for established scars have remained limited and often unsatisfying. Surgery, laser therapy, or injections can sometimes help, but they are invasive, expensive, and painful. Worse, they do not always deliver consistent results. This has left a gap in care—one that researchers at the University of Western Australia and the Fiona Wood Foundation are now beginning to fill.

The Science of Scarring

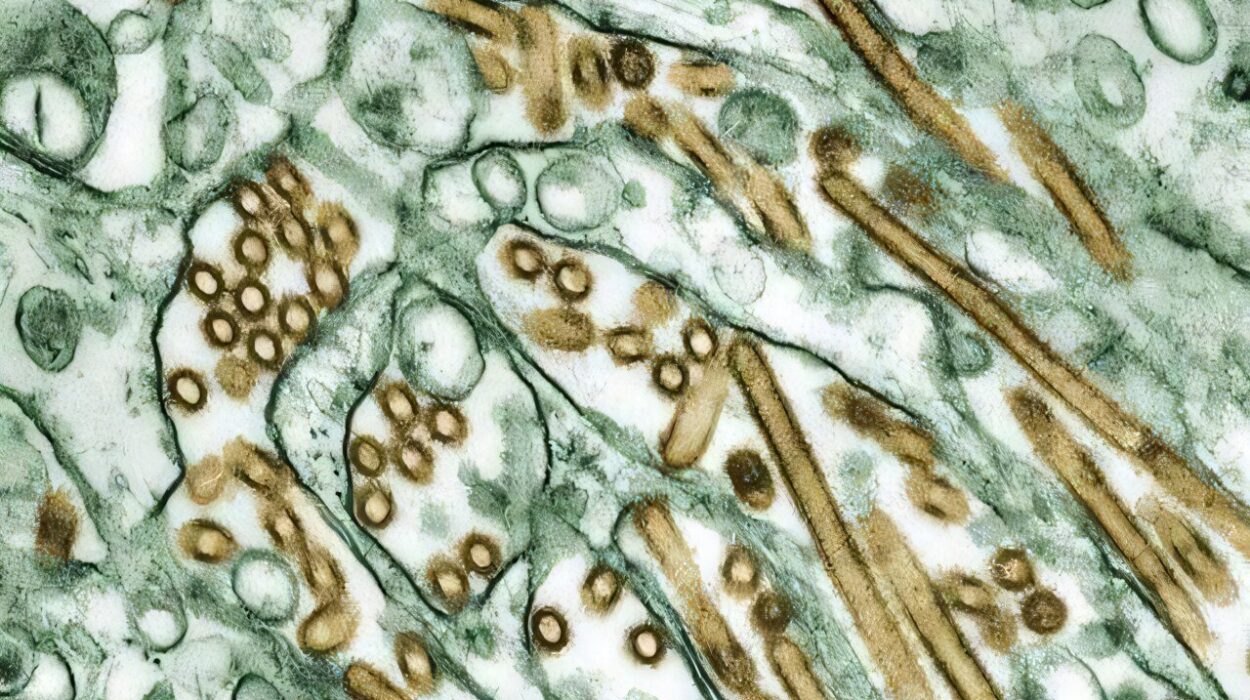

To understand why this breakthrough matters, it’s important to look at what happens inside a scar. When the body repairs a deep injury, collagen—a strong, fibrous protein—rushes in to form new tissue. But the collagen strands don’t just sit loosely beside one another; they are chemically bound together in a process called cross-linking.

This cross-linking is driven by enzymes known as lysyl oxidases, which act like natural glue, tying collagen fibers tightly together. While this makes tissue strong, it also makes it stiff. In scars, the excess cross-linking leads to dense, fibrotic tissue that resists normal turnover and repair. The result is skin that looks and feels different: less elastic, harder, and often raised above surrounding tissue.

Reducing this excessive cross-linking has long been a tantalizing goal in scar research. And now, for the first time, a potential therapy seems to be making meaningful progress.

A First-in-Human Clinical Trial

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine, describes the first clinical trial of PXS-6302, a topical inhibitor designed to block lysyl oxidase activity. This was not a casual or anecdotal exploration, but a rigorously designed Phase I randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial—the gold standard of medical testing.

The trial enrolled 50 adults with mature scars—those at least one year old—through Fiona Stanley Hospital in Perth. This is significant because established scars are notoriously difficult to change; most treatments are far more effective on fresh injuries.

The study unfolded in two parts:

- Cohort 1: Eight participants applied 2% PXS-6302 cream daily to a small (10 cm²) scar area for three months. This group helped establish safety and tolerability.

- Cohort 2: Forty-two participants were randomized to either PXS-6302 or placebo. In the first week, participants applied the cream daily; from week two onward, they switched to three times per week, based on safety observations from Cohort 1.

The cream was delivered using a microdosing device that precisely applied 200 μl per treatment, ensuring consistent dosing at 4 mg of PXS-6302.

What the Researchers Found

The findings were striking. First and most importantly, PXS-6302 was generally safe and well tolerated. No serious adverse events occurred. Some participants experienced mild to moderate irritation at the application site—enough to prompt six people to discontinue—but this is not unusual for topical treatments and considered manageable in early-phase studies.

Second, the cream stayed local to the scar tissue. Blood tests showed minimal systemic absorption, which is crucial: the treatment acted where it was needed, without spreading through the body.

Third, and perhaps most exciting, the drug appeared to alter the biology of the scars themselves. Scar biopsies revealed that lysyl oxidase activity dropped in treated areas, directly confirming that the drug was hitting its target. Over three months, collagen-related signals—like hydroxyproline and total protein levels—decreased in treated scars, while placebo scars showed the opposite trend, with collagen signals increasing.

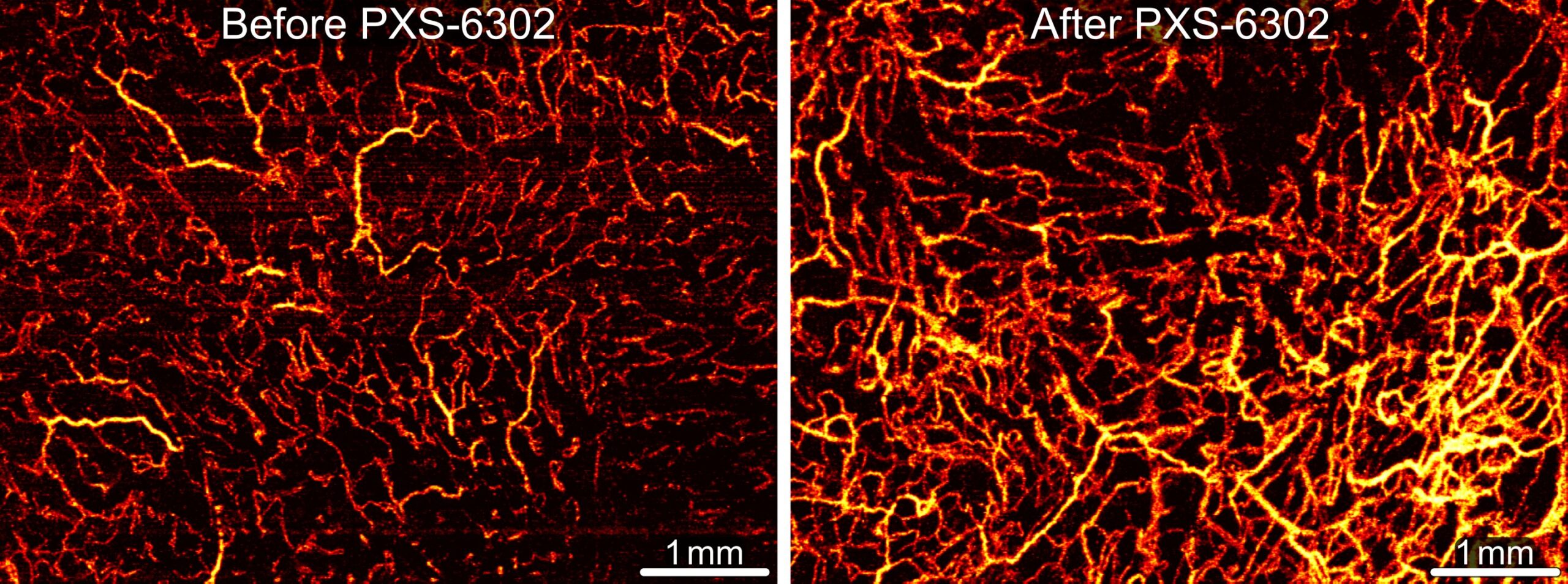

Advanced imaging offered another window into change. Optical scans showed that treated scars developed denser networks of small blood vessels and increased tissue attenuation—signs that the extracellular matrix was being remodeled in a healthier direction. Placebo-treated scars did not show the same vascular improvements.

Why This Matters

For decades, scar research has been constrained by the assumption that old scars are fixed and unchangeable. This trial suggests otherwise. By targeting the biochemical foundation of scar stiffness—excessive collagen cross-linking—researchers demonstrated that even long-standing scars may be biologically malleable.

While the Phase I trial was not designed to measure cosmetic improvements directly, the measurable changes in extracellular matrix markers and scar microstructure are powerful signals. They suggest that future studies, with larger cohorts and longer follow-ups, could reveal visible and functional improvements in scar texture, softness, and appearance.

A New Era of Scar Care

If subsequent trials confirm these findings, PXS-6302 could represent a revolution in scar treatment. Unlike surgery or lasers, it is non-invasive, easy to apply, and targets the underlying biology of scarring rather than just the surface. For patients, this could mean fewer painful interventions, lower costs, and more effective long-term outcomes.

But perhaps just as importantly, it could mean a shift in how scars are perceived. No longer unchangeable markers of the past, scars might become treatable conditions—dynamic tissues capable of healing and renewal.

Looking Ahead

The authors of the study are cautious but hopeful. They emphasize that these results are preliminary and must be validated in larger Phase II trials that focus not just on safety and biological markers, but also on clinical improvements in scar appearance and texture.

Yet even at this early stage, the findings resonate deeply. They remind us that scars—physical and emotional alike—are not always permanent. Science continues to challenge the boundaries of what we thought was fixed, offering new pathways toward healing.

Conclusion: Hope Written in Skin

The trial of PXS-6302 at the University of Western Australia and the Fiona Wood Foundation is more than a medical study—it is a story of hope. For the millions of people worldwide living with scars that affect not just their skin but their confidence and quality of life, this work offers a glimpse of a different future.

A cream applied to the skin, working quietly beneath the surface, may one day transform the story of scars from one of permanence to one of possibility. And that possibility is profoundly human: the chance to move forward not just with healed wounds, but with renewed self-belief.

More information: Natalie Morellini et al, A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 trial of the topical pan–lysyl oxidase inhibitor PXS-6302 in mature scars, Science Translational Medicine (2025). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adv2471