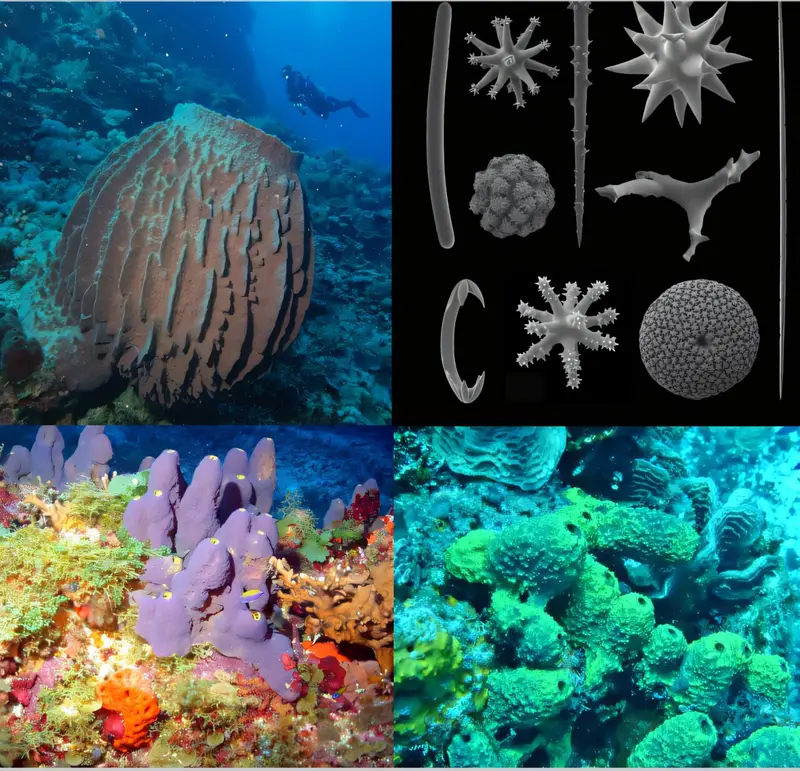

In the quiet depths of the ancient ocean, long before the first footprints marked the land, a mystery was brewing. It is a mystery that has haunted the halls of paleontology for decades, centered on one of Earth’s most enigmatic and ancient survivors: the sponge. While they may seem like simple, sedentary creatures today, sponges represent a foundational chapter in the history of life. However, for years, science was stuck in a frustrating deadlock. On one side, the chemical whispers found in ancient rocks and the complex code of genetics suggested that sponges had been around for at least 650 million years. On the other side stood the cold, hard evidence of the fossil record, which stubbornly refused to show a single trace of a sponge until nearly 100 million years later.

This discrepancy created a massive “ghost lineage”—a period of time where an animal should exist according to biology, but remains invisible to geology. The search for the missing ancestors of the Porifera phylum felt like looking for a ghost in a cathedral; the signs of their presence were everywhere in the DNA of their descendants, yet their physical bodies were nowhere to be found in the stone. Now, an international team of researchers led by Dr. M. Eleonora Rossi from the University of Bristol has finally peered through the fog of deep time to explain why these ancient pioneers remained hidden for so long.

The Ghost in the Ancient Stones

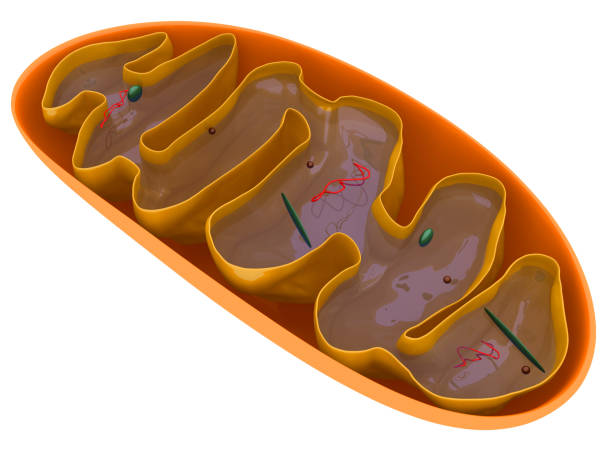

To understand why sponges were so hard to find, one must look at what makes a sponge a sponge in the modern world. Today’s sponges are famous for their skeletons, which are not made of bone, but of millions of microscopic, glass-like needles called spicules. These tiny structures are remarkably durable. When a sponge dies, these needles sink into the seafloor and become part of the sediment, creating an incredibly reliable fossil record. Because these mineralized spicules are so easy to preserve, scientists expected to find them in any rock layer where sponges lived.

The oldest of these needles date back to roughly 543 million years ago, during the late Ediacaran Period. If sponges had truly evolved 650 million years ago, as some genetic data suggested, why were the 600-million-year-old rocks completely empty of these needles? This absence led many to doubt the early evolutionary estimates, suggesting that perhaps sponges were much younger than we thought. The conflict wasn’t just a matter of dating; it was a fundamental disagreement between the biological “clock” found in DNA and the physical “archive” found in the Earth’s crust.

Mapping the Tree of Life

Dr. Rossi and her team decided to tackle this contradiction by rebuilding the sponge family tree from the ground up. They didn’t just look at a few traits; they harnessed high-quality data from 133 protein-coding genes across a vast array of species. By combining this massive genetic dataset with known fossil evidence, they were able to construct a refined evolutionary timescale. Their findings shifted the window of origin slightly, placing the birth of the first sponges between 600 and 615 million years ago.

While this new date helped close the gap with the known fossil record, it didn’t fully explain the missing 100 million years of needles. To find the answer, the team turned their attention away from the age of the animals and toward the architecture of their bodies. They began to investigate the very nature of the sponge skeleton. What they discovered was a revelation that turned traditional assumptions upside down: the iconic glass needles we associate with sponges today were not a “day one” invention. Instead, the team found that spicules evolved independently in different sponge groups at different times.

The Secret of the Soft Bodied Ancestor

The realization that skeletons were a later addition changed everything. If the first sponges didn’t have needles, they wouldn’t leave a traditional fossil record. According to Dr. Rossi, the earliest sponges were entirely soft-bodied. They were fleshy, delicate organisms that lacked any mineralized parts. When these creatures died, they decayed completely, leaving no trace in the prehistoric mud. This explains the geological silence; there were simply no hard parts to preserve.

This theory was bolstered by the observations of Dr. Ana Riesgo, who noted that modern sponge skeletons are surprisingly diverse. Some sponges build their support structures out of calcite, the same mineral found in chalk, while others use silica, which is essentially glass. When the team peered into the genomes of these modern sponges, they found that entirely different sets of genes were responsible for building these different skeletons. This was the smoking gun: if all sponges had inherited their skeletons from a single common ancestor, they would likely use the same genetic toolkit and the same minerals. Instead, it appears that different lineages “invented” their skeletons separately long after the groups had diverged.

Modeling the Invisible Past

To prove that the earliest sponges were indeed soft and squishy, the researchers employed a sophisticated statistical tool known as a Markov process. This is a type of predictive model usually reserved for complex systems like weather forecasting, search engine algorithms, and financial markets. By feeding the model different scenarios of how sponge skeletons might have changed over millions of years, the team could calculate which path was most likely.

The results were overwhelming. Almost every version of the statistical model strongly rejected the idea that the first sponges possessed mineralized skeletons. The only models that suggested otherwise were considered unrealistic, as they treated all types of minerals as if they were the same. The math confirmed the biology: the “missing” sponges weren’t missing because they weren’t there; they were missing because they were too soft to be immortalized in stone. This discovery fundamentally challenges the idea that spicules were the primary driver of early sponge diversification. If they weren’t building glass houses to survive, some other unknown factor was pushing these animals to evolve and spread across the ancient seas.

Why the First Reef Builders Matter

This research is about much more than just the origin of sponges; it is a window into the dawn of the animal kingdom. Sponges are the first lineage of reef-building animals to appear on Earth. In fact, many scientists believe they might be the very first animal lineage of any kind to evolve. By pinpointing when and how they appeared, we are uncovering the blueprint for all animal life that followed.

Understanding the rise of the sponge is essential for understanding how life and the planet co-evolved. These early, soft-bodied pioneers were the architects of the first reef systems, changing the chemistry of the oceans and the structure of the seafloor. Their emergence triggered a chain reaction that altered the environment forever, paving the way for more complex life forms. From these humble, squishy beginnings in a world without skeletons, the stage was set for the arrival of the entire animal kingdom, eventually leading to the diverse world we inhabit today—humans included. By solving the mystery of the missing fossils, we aren’t just learning about sponges; we are uncovering the first chapters of our own story.

Study Details

Independent origins of spicules reconcile paleontological and molecular evidence of sponge evolutionary history, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adx1754