Beneath the shimmering blue skin of Earth’s oceans, an invisible crisis is unfolding—quietly, steadily, and with consequences as vast as the waters themselves. According to a groundbreaking new study published in Global Change Biology, an international team of scientists now believes that parts of the ocean have already crossed a critical environmental threshold—one of the planet’s so-called “planetary boundaries.” This time, it’s ocean acidification.

The implications are sobering. Drawing from decades of physical and chemical measurements, data retrieved from ancient ice cores, and computer simulations layered with ecological insights, researchers have concluded that vast stretches of the world’s ocean surface—and even more of its subsurface—have acidified past safe limits.

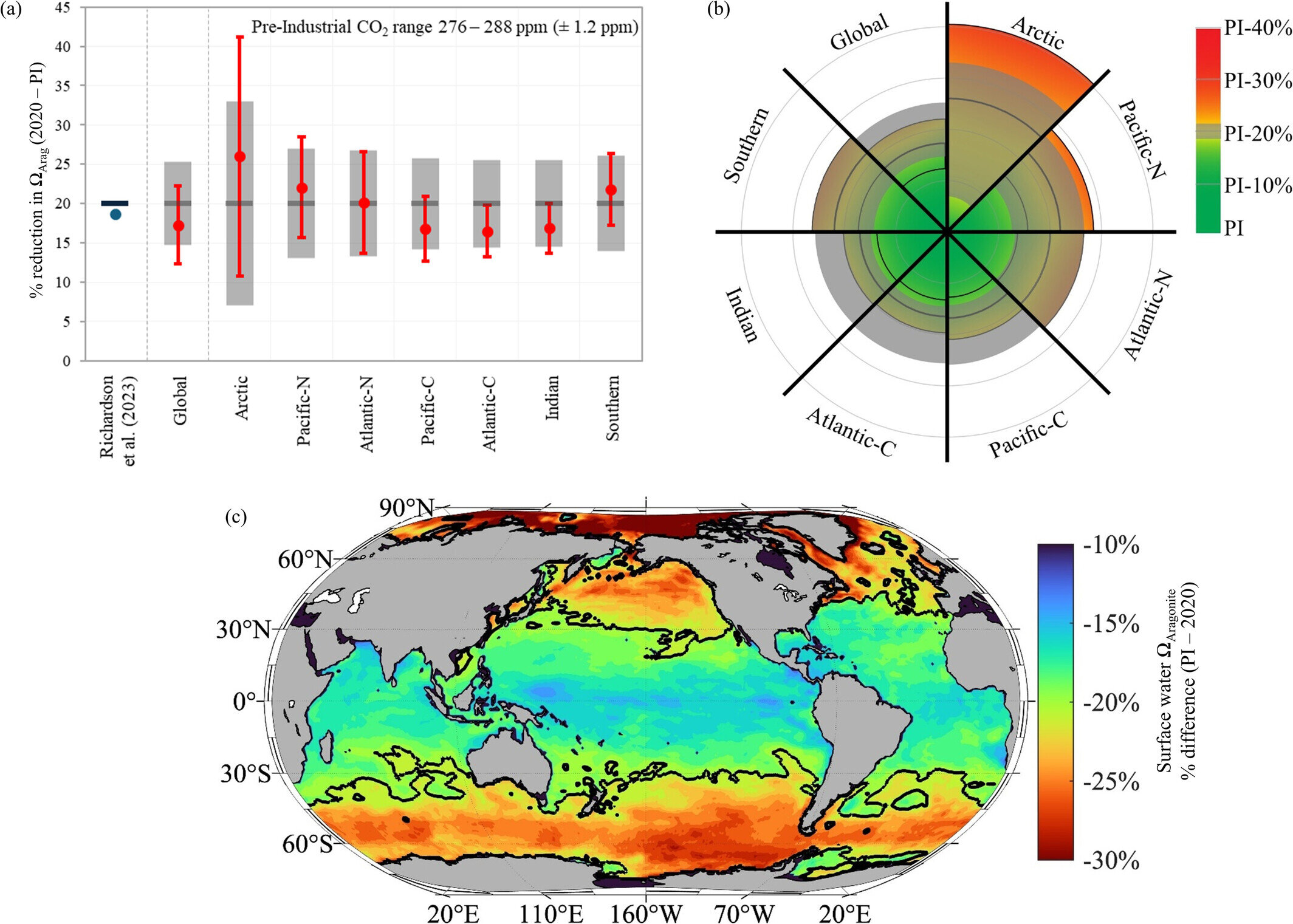

The numbers are stark: approximately 40% of surface waters and 60% of subsurface ocean zones have already breached this boundary. And the slide into dangerous territory didn’t start yesterday. According to the study, it began at least five years ago.

What Lies Beneath: Understanding the Invisible Shift

To understand the gravity of this news, it helps to journey beneath the surface—to the molecular ballet between the ocean and the atmosphere. For millions of years, the ocean has acted as Earth’s carbon sponge, quietly absorbing carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the air. But that natural partnership has turned toxic in the age of fossil fuels.

As humanity has pumped unprecedented levels of CO₂ into the atmosphere, the oceans have taken in more and more of it—now absorbing roughly a quarter of all carbon emissions. But this uptake comes at a cost. When carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it undergoes a chemical transformation, forming carbonic acid. That acidification strips the ocean of carbonate ions—essential building blocks for creatures like corals, clams, and countless shell-forming organisms.

As their calcium carbonate shells thin and weaken, so too do the coral reefs and underwater habitats they support. A weakened foundation means collapsing ecosystems—once-thriving marine gardens reduced to skeletal remains.

“We’ve known that ocean acidification was a major threat,” said one of the study’s co-authors. “But to discover that we’ve already crossed this planetary boundary in such large portions of the ocean—this raises the urgency to a new level.”

Planetary Boundaries: Nature’s Alarm Bells

The concept of planetary boundaries isn’t new, but it has never felt more pressing. Developed by Earth system scientists over the last two decades, these boundaries mark thresholds that, if crossed, could destabilize the planet’s ability to support human life.

There are nine such boundaries—including climate change, biodiversity loss, freshwater use, and atmospheric aerosol pollution. Until recently, scientists warned that six of these boundaries had already been pushed beyond safe limits. With this latest study, that number may now be seven.

Crucially, these boundaries are not tipping points in the dramatic, irreversible sense. They are warnings—lines drawn in the sand before the cliff’s edge. Once crossed, the risk of irreversible change increases. But the door to prevention is still ajar.

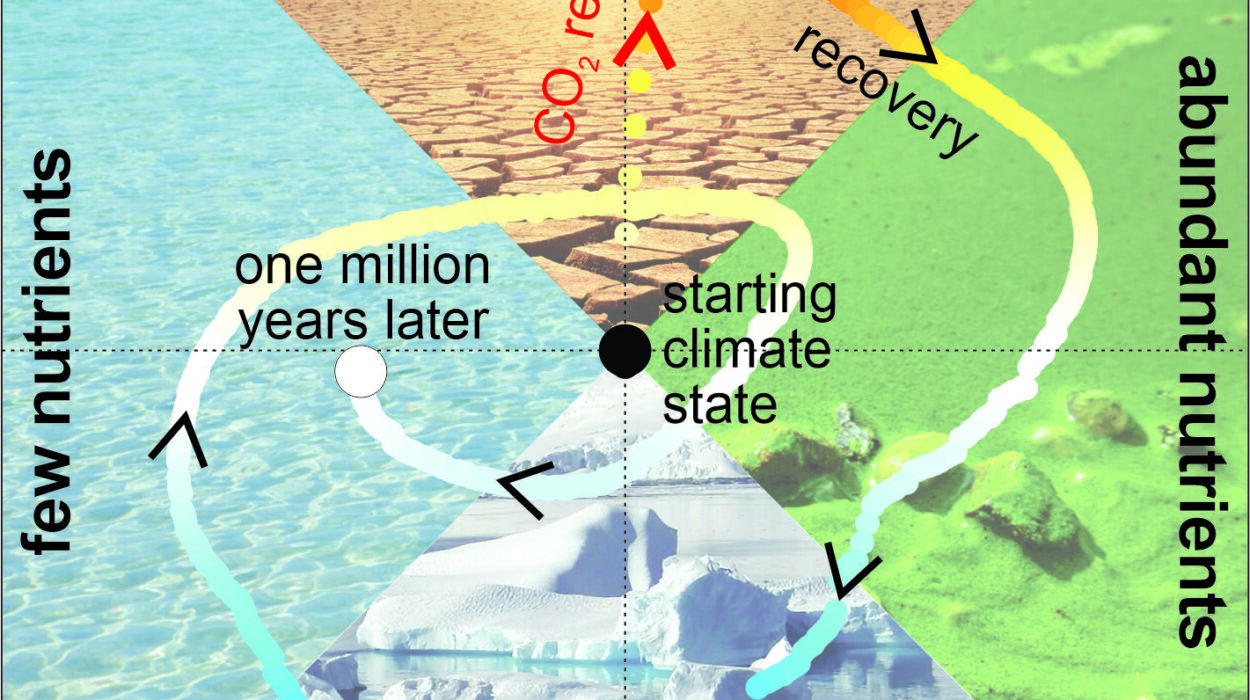

“In the case of ocean acidification, there’s still time to turn back,” the study’s authors emphasized. “This is not the end of the story—unless we allow it to be.”

Echoes from the Deep: Data Born of Ice and Stone

The team behind this study combined old and new science in a way that adds weight to their conclusions. Ice cores from polar regions preserved a chemical snapshot of Earth’s ancient atmosphere, revealing pre-industrial baselines for carbon dioxide levels and ocean chemistry. By layering these insights with modern ocean measurements—from satellites, buoys, and deep-sea probes—they were able to see a disturbing pattern emerge.

In areas where upwelling brings deep, carbon-rich waters to the surface, acidification was particularly intense. Some of these regions, including key parts of the Pacific and Southern Oceans, have become laboratories of change—where the past, present, and future of Earth’s climate system collide in the churn of waves.

The researchers modeled changes in calcium carbonate availability—specifically aragonite and calcite, two minerals crucial for marine organisms that build shells and skeletons. They found that concentrations have declined by 20% or more across wide swaths of the ocean, the threshold used to define the acidification boundary.

The Cost of Silence: Coral Reefs, Food Chains, and Human Livelihoods

To some, acidification might seem like a remote or abstract problem—out of sight, out of mind, dissolved in water too vast to comprehend. But its consequences ripple directly to human shores.

Coral reefs, already battered by warming seas and bleaching events, are among the first and hardest hit. As the building blocks of reef systems weaken, so too do the homes of countless marine species. From colorful reef fish to the predators that rely on them, entire food chains begin to falter.

For millions of people around the world, especially in coastal communities, this is not just about biodiversity—it’s about food, income, and survival.

Small-scale fishers, aquaculture workers, and communities dependent on tourism are already beginning to feel the pinch. Shellfish farms report thinning oyster shells. Commercial fisheries face declining yields. And all of this, researchers warn, is just the beginning if acidification continues unchecked.

Hope Still Afloat

Despite the grim findings, the study’s authors are not without hope. One of the study’s key messages is that planetary boundaries are not immutable endpoints—they are warnings. And in the case of ocean acidification, the primary driver is known, well understood, and still within our control: carbon emissions.

“If we dramatically reduce CO₂ emissions, we can stabilize or even reverse acidification trends,” the researchers wrote. “The ocean can recover. But we have to act quickly.”

They also stressed the importance of ocean monitoring and international cooperation. Current efforts to track ocean chemistry are fragmented and underfunded. To understand how fast the crisis is unfolding—and where intervention might still be most effective—scientists need more data, not less.

A Moment of Reckoning

This new study doesn’t just sound an alarm for the oceans—it adds to a growing body of evidence that humanity is pushing Earth’s systems past safe limits, sometimes without fully realizing the consequences. The ocean has long buffered us from the worst effects of climate change, absorbing both heat and carbon. But it can only absorb so much.

Now, with over half the ocean’s surface waters and a majority of its subsurface zones already beyond safe chemical thresholds, the question is not whether we’ve gone too far—but whether we are willing to turn around.

In the quiet swirl of ocean currents, the chemistry of life is changing. The planet is speaking—not in dramatic explosions, but in subtle shifts. In shellfish that struggle to grow. In reefs that crumble. In the ancient code of carbon and water, rewritten by human hands.

There is still time to listen.

But not forever.

Reference: Helen S. Findlay et al, Ocean Acidification: Another Planetary Boundary Crossed, Global Change Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1111/gcb.70238