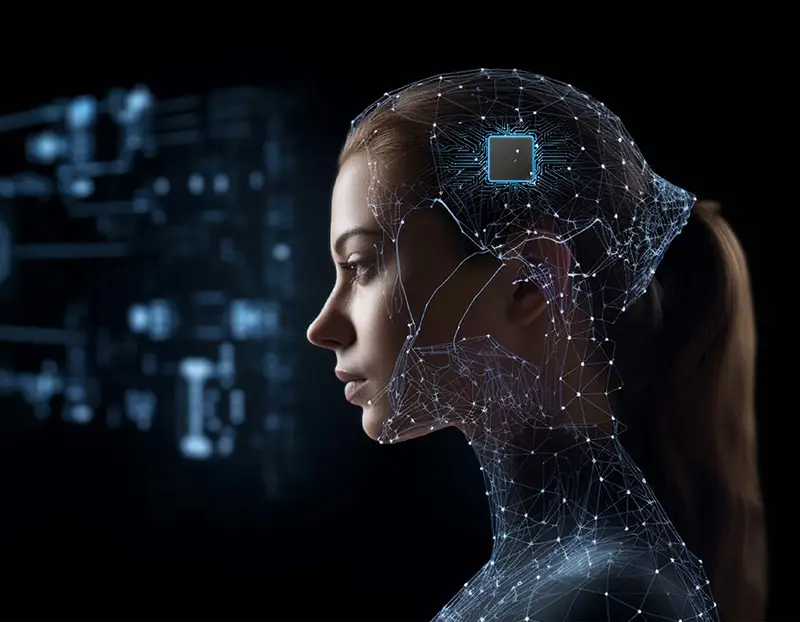

Neuralink sits at the intersection of science fiction and laboratory reality. For centuries, humans have dreamed of communicating directly with the brain, bypassing muscles, keyboards, and spoken words. Ancient myths imagined telepathy as magic. Modern science reframes that dream as engineering. Neuralink, a company founded in 2016, represents one of the boldest efforts to transform that ancient fantasy into a medical and technological tool. At its core, Neuralink is about building a bridge between neurons and machines, allowing electrical signals in the brain to be read, interpreted, and potentially written back into neural tissue.

Emotionally, the idea of brain–computer interfaces touches something deep. The brain is where memory, identity, and feeling live. To connect a machine to it feels intimate and unsettling, hopeful and frightening at the same time. The promise is immense: restoring movement to paralyzed patients, giving voice to those who cannot speak, treating neurological disorders at their source. The risks are equally profound: misunderstanding the brain, harming it, or reshaping human experience in ways we do not yet grasp. Neuralink is not just a technology. It is a test of how far humanity is willing to go in merging biology with machines.

The Foundations of Brain-Computer Interfaces

Before Neuralink, there was already a long scientific tradition of studying how brains generate electrical signals. Neurons communicate using tiny electrical impulses called action potentials. These impulses travel along nerve cells and across synapses using chemical messengers. When many neurons fire together, their collective electrical activity can be measured.

In the twentieth century, scientists learned how to record these signals from outside the skull using electroencephalography, or EEG. EEG showed that the brain produces rhythms associated with sleep, attention, and disease. Later, electrodes implanted directly into brain tissue allowed far more precise recordings. These invasive methods revealed that individual neurons encode information about movement, sensation, and even abstract ideas like intention.

From this research emerged the concept of a brain–computer interface, often abbreviated as BCI. A BCI is a system that detects neural activity, translates it into digital information, and uses that information to control an external device. Early BCIs allowed monkeys to move robotic arms by thinking about movement. Human trials followed, enabling paralyzed patients to move cursors or robotic limbs using their minds. These achievements proved that the brain’s language could, at least in part, be decoded.

Neuralink did not invent BCIs, but it aims to refine and scale them. Its goal is not only to read signals but eventually to write them back, creating a two-way conversation between brain and machine. This ambition requires extraordinary precision, stability, and safety. The brain is delicate, and any foreign object inside it risks causing inflammation, scarring, or infection. To succeed, Neuralink must make technology that behaves almost like a natural extension of neural tissue.

The Science of Neurons and Electrical Signals

Understanding Neuralink requires understanding what neurons are and how they communicate. Neurons are specialized cells designed to transmit information using electrical and chemical signals. Each neuron has dendrites that receive signals, a cell body that processes them, and an axon that sends signals onward. When a neuron fires, it generates an action potential, a rapid change in electrical voltage across its membrane.

These action potentials are not random. Patterns of firing encode information. In the motor cortex, certain neurons fire when you move your hand left, others when you move it right. In the visual cortex, neurons respond to edges, motion, or color. In the language centers, neurons fire in patterns associated with speech and comprehension.

Electrodes placed near neurons can detect these electrical changes. The closer the electrode is to the neuron, the clearer the signal. Surface electrodes pick up broad patterns, while implanted microelectrodes can isolate activity from individual cells. Neuralink’s approach relies on ultra-thin electrodes inserted directly into brain tissue, designed to record from many neurons simultaneously.

The challenge is enormous. The brain contains about eighty-six billion neurons, each forming thousands of connections. Recording from even a tiny fraction of them requires careful placement and advanced signal processing. Electrical noise, biological movement, and immune responses all interfere with stable recordings. Neuralink’s technology attempts to solve these problems through materials science, robotics, and machine learning.

Neuralink’s Device Architecture

Neuralink’s implant is often described as a coin-sized device placed into the skull. This device contains electronics for amplifying and transmitting neural signals. From it extend flexible threads thinner than a human hair. These threads are embedded with electrodes that can detect neural activity.

The flexibility of the threads is crucial. Traditional electrodes are relatively stiff compared to brain tissue, which moves slightly with each heartbeat and breath. A stiff electrode can damage surrounding tissue over time. Neuralink’s threads are designed to move with the brain, reducing mechanical stress and inflammation.

Insertion of these threads requires precision beyond human hands. Neuralink uses a robotic system to implant them. The robot can avoid blood vessels visible on the brain’s surface, minimizing bleeding and injury. It places each thread into a specific location, targeting particular brain regions associated with movement or sensation.

Once implanted, the device collects neural signals and transmits them wirelessly to an external computer. There, algorithms decode the patterns into commands. For example, if neurons associated with moving a hand fire in a certain way, the system interprets that as an intention to move, and translates it into movement of a cursor or robotic limb.

The implant is also designed to be biocompatible and sealed, preventing bodily fluids from damaging electronics and preventing electronics from harming tissue. Power management is another challenge. The device must operate with minimal heat, as excess warmth can damage neurons. It must also run efficiently to avoid frequent surgeries for battery replacement.

The Surgical and Biological Challenge

Placing technology into the brain is not like installing a chip in a phone. The brain is living tissue with immune defenses. When a foreign object enters, the body may respond by forming scar tissue around it. This response can isolate electrodes from neurons, weakening signals over time. Neuralink’s flexible threads aim to reduce this reaction, but long-term stability remains a critical question.

Surgery itself carries risks. Infection, bleeding, and unintended damage to brain regions can have serious consequences. Neuralink’s robotic approach is designed to make implantation safer and more precise, but no surgery is without danger. A central scientific and ethical challenge is determining when potential benefits outweigh these risks.

Animal experiments have been essential for testing these devices. Studies in rodents and primates have demonstrated that Neuralink’s implants can record neural activity and enable tasks like moving a cursor or playing simple games. These experiments also test durability and biological response over months or years.

Human trials represent a much higher bar. Regulatory agencies require evidence that devices are safe and likely to benefit patients. Neuralink’s initial human studies have focused on people with paralysis, aiming to restore communication or control of digital devices. These applications align with existing BCI research but seek to improve performance and ease of use.

Decoding Thought into Action

The heart of Neuralink’s promise lies in decoding. When you decide to move your hand, neurons in your motor cortex fire in characteristic patterns. By recording these patterns, a computer can learn to associate them with specific movements. Machine learning algorithms play a central role here. They analyze large datasets of neural signals and corresponding actions, gradually improving their predictions.

Decoding is not mind reading in the science-fiction sense. The system does not understand abstract thoughts or emotions. It detects patterns related to specific tasks. For example, imagining moving your hand produces similar neural activity to actually moving it. The implant can use this activity to move a cursor or type letters on a screen.

This process requires training. Users must practice generating consistent neural signals while the system learns to interpret them. Over time, the brain itself adapts, forming new neural pathways that make control more natural. This phenomenon, known as neuroplasticity, is central to BCI success. The brain reshapes itself to accommodate the interface, much like it adapts when learning to use a new tool.

Emotionally, this adaptation can be powerful. For someone paralyzed, regaining the ability to communicate or interact with the world through thought alone can feel like reclaiming part of their identity. The interface becomes not just a device, but an extension of the self.

Writing Information Back into the Brain

Reading neural signals is only half of the story. Neuralink also aims to stimulate neurons, sending information back into the brain. Electrical stimulation has been used for decades in medicine. Deep brain stimulation helps treat Parkinson’s disease by modulating abnormal neural activity. Cochlear implants stimulate auditory nerves to restore hearing. Retinal implants attempt to restore partial vision by stimulating visual pathways.

Neuralink envisions a more general system, capable of stimulating specific neurons with high precision. In theory, this could restore sensory input, correct dysfunctional circuits, or enhance learning by reinforcing certain patterns of activity. Writing information into the brain raises profound questions. What does it mean to alter neural activity directly? Where is the boundary between therapy and enhancement?

Scientifically, stimulation requires careful control. Too much current can damage tissue or disrupt normal function. Too little may have no effect. The timing of stimulation is also crucial, as neurons communicate in millisecond-scale pulses. Neuralink’s hardware and software must coordinate with this biological rhythm to achieve meaningful results.

Medical Applications and Human Hope

The most immediate and ethically accepted applications of Neuralink lie in medicine. Paralysis caused by spinal cord injury or neurodegenerative disease can trap a person’s mind inside an unresponsive body. BCIs offer a way to bypass damaged pathways, allowing thoughts to control external devices directly.

Speech loss due to conditions like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis can isolate individuals socially and emotionally. A neural interface that translates intended speech into text or sound could restore a voice where none exists. Such technology does not merely improve convenience; it restores agency and connection.

Neurological disorders such as epilepsy, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder involve abnormal patterns of neural activity. Targeted stimulation might correct these patterns more precisely than drugs, reducing side effects and increasing effectiveness. Memory loss, whether from injury or disease, could someday be treated by strengthening or replicating neural circuits involved in recall.

Each of these possibilities carries emotional weight. They are not about making humans faster or smarter, but about healing what has been broken. Neuralink’s narrative often emphasizes this medical mission, grounding its futuristic vision in human need.

Ethical Dimensions of Brain Interfaces

Connecting a machine to the brain raises ethical questions that go beyond typical medical technology. The brain is the seat of thought, personality, and autonomy. Intervening at this level touches core aspects of what it means to be human.

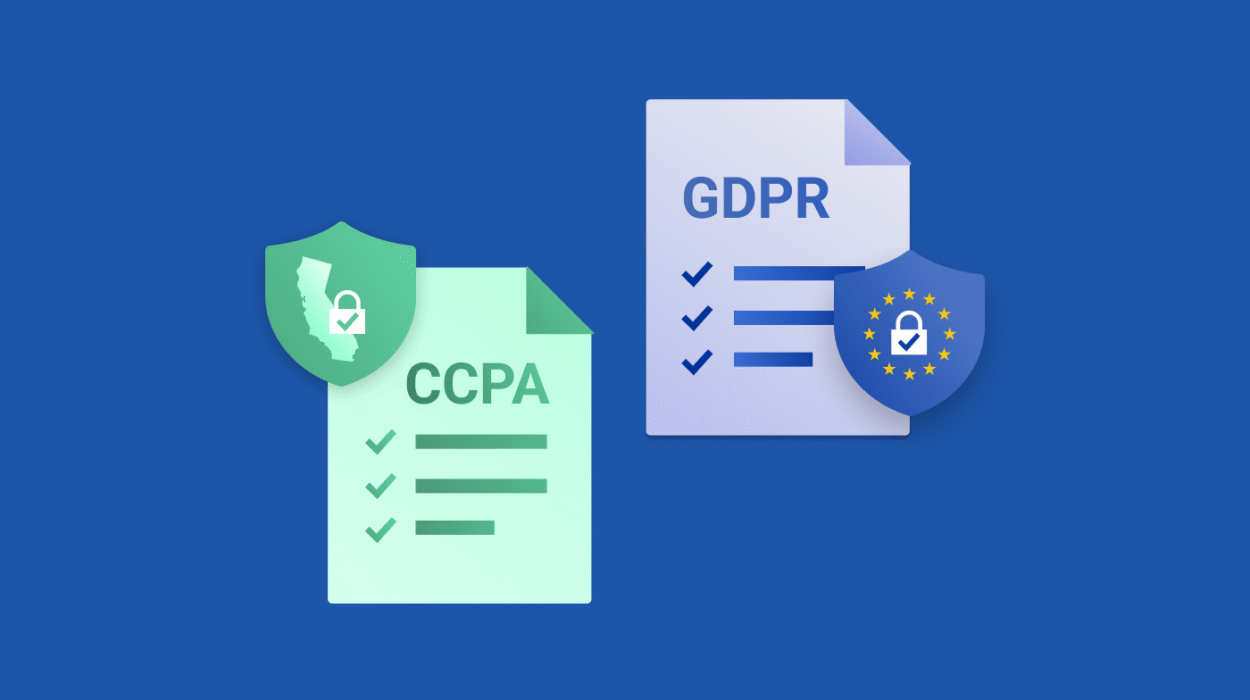

One concern is privacy. Neural signals contain information about intentions and possibly emotions. Who owns this data? How is it protected? If a device transmits neural activity wirelessly, could it be intercepted or misused? Ensuring security is not just a technical issue but a moral one.

Another concern is consent and control. A patient may agree to an implant to restore lost function, but what happens if the device’s capabilities expand? Could future versions influence mood or decision-making? Safeguards must ensure that users remain in control of their own minds.

There is also the question of inequality. Advanced neural interfaces may be expensive and accessible only to a privileged few. If such technology eventually offers enhancement rather than just therapy, social divisions could deepen. The idea of augmented humans raises fears of a world where biology and technology create new forms of class distinction.

Ethics must therefore evolve alongside engineering. Neuralink operates within regulatory frameworks, but societal debate will shape what is considered acceptable. The science may enable possibilities, but values determine which paths are taken.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is essential to Neuralink’s vision. The raw data from neural electrodes is complex and noisy. AI algorithms sift through this data, identifying meaningful patterns and translating them into commands. Without machine learning, real-time decoding would be nearly impossible.

AI also enables adaptation. Each brain is unique. Neural activity patterns differ between individuals and even within the same person over time. Algorithms must adjust continuously, learning from new data to maintain accuracy. This dynamic learning mirrors the brain’s own plasticity, creating a partnership between biological and artificial intelligence.

Emotionally, this partnership feels symbolic. Human cognition and machine computation meet at the boundary of the skull. The brain learns to communicate in a digital language, while the computer learns to interpret a biological one. This convergence challenges the traditional separation between human and machine.

Public Perception and Cultural Impact

Neuralink does not exist in a vacuum. It operates in a cultural landscape shaped by science fiction, fear of surveillance, and fascination with technology. Stories of mind control and cybernetic enhancement color public imagination. As a result, Neuralink’s work provokes reactions ranging from awe to anxiety.

Media portrayals often oscillate between utopian and dystopian visions. Some see Neuralink as a path to curing disease and expanding human potential. Others worry about loss of privacy, identity, or autonomy. These emotional responses are not irrational; they reflect the deep significance of the brain in human self-understanding.

Public trust will depend on transparency, demonstrated safety, and clear boundaries between therapy and enhancement. The narrative surrounding Neuralink matters as much as the hardware itself. It must be framed not as domination of the brain, but as collaboration with it.

Limitations and Scientific Unknowns

Despite its ambition, Neuralink faces formidable scientific unknowns. The brain is not a simple machine with clearly defined inputs and outputs. It is a dynamic, adaptive system shaped by experience, emotion, and environment. Decoding neural activity for simple tasks is possible, but scaling this to complex cognition remains far beyond current capability.

Long-term implantation is another unknown. How will brain tissue respond over decades? Will electrodes degrade? Will immune responses eventually interfere with function? These questions can only be answered through long-term studies.

There is also the challenge of interpretation. Neural signals are context-dependent. A pattern associated with movement today may change tomorrow. The brain is not static, and interfaces must evolve with it. This fluidity complicates both engineering and medical use.

The Future of Neuralink and Brain Interfaces

Looking forward, Neuralink envisions a future where neural interfaces are as common as pacemakers. In this vision, people with neurological conditions regain lost abilities. Communication becomes faster and more direct. Learning might be accelerated by guiding neural plasticity.

Whether this future arrives depends on science, regulation, and public acceptance. Breakthroughs in materials, robotics, and AI will shape what is possible. Ethical frameworks will shape what is permitted. Cultural attitudes will shape what is desired.

It is likely that early successes will remain focused on therapy. Enhancement will provoke more resistance and debate. Over time, as safety improves and understanding deepens, boundaries may shift. History shows that technologies once seen as unnatural often become routine. Yet the brain’s intimate role in identity ensures that this shift will be slower and more cautious.

A Reflection on Humanity and Machines

Neuralink forces humanity to confront a profound question: what does it mean to extend the mind beyond the body? Tools have always extended human capability. A stick extends the arm. A telescope extends the eye. A computer extends memory and calculation. A brain–computer interface extends thought itself into the physical world.

This extension blurs the line between internal and external. When a person moves a cursor with their mind, where does intention end and action begin? The interface becomes part of the cognitive loop. In this sense, Neuralink is not just a device but a philosophical experiment.

Emotionally, this blending can inspire both hope and unease. Hope, because it suggests that human limitations are not final. Unease, because it challenges the idea of a self-contained mind. Yet perhaps this challenge is not entirely new. Language, writing, and technology have always reshaped thought. Neuralink may simply be a more direct continuation of that process.

Conclusion: The Science and the Soul

Neuralink represents a convergence of neuroscience, engineering, and imagination. Scientifically, it builds on decades of research into neural signals, electrodes, and machine learning. Technologically, it pushes the limits of what can be safely implanted in the brain. Ethically, it forces reflection on privacy, autonomy, and equality.

Emotionally, it embodies a human longing to overcome suffering and isolation. For those trapped by paralysis or disease, a neural interface offers a bridge back to the world. For society, it offers a glimpse of a future where mind and machine cooperate more intimately than ever before.

The science behind Neuralink is grounded in neurons, electricity, and algorithms. But its significance reaches beyond laboratories. It touches the ancient question of how humans relate to their own minds. In seeking to connect brains to computers, Neuralink is not merely inventing a new tool. It is exploring the boundary between biology and technology, between self and system, between what we are and what we might become.