In a fascinating study published in PLOS ONE, researchers revealed a widespread mismatch between what people think the opposite sex finds attractive and what is actually preferred—particularly when it comes to facial femininity and masculinity. Using interactive 3D models of human faces, the research team uncovered that women tend to overestimate how feminine men like their partners’ faces to be, while men consistently overestimate the degree of facial masculinity women find appealing. These misperceptions don’t just exist in the abstract; they are deeply tied to how people view their own faces and idealize romantic attractiveness.

Shifting Standards: From Ancient Curves to Modern Fitness

The concept of an ideal body or face has never been static. Across history and cultures, perceptions of beauty have evolved, often shaped by prevailing societal values, media, and trends. The traditional Western male ideal has long favored the tall, broad-shouldered, muscular physique with a V-shaped torso—shoulders wide, waist narrow, and muscles well-defined. In contrast, the female ideal has centered around an hourglass figure, with a slim waist flanked by full hips and a proportional bust.

Yet, these standards are far from universal or timeless. In earlier centuries, for instance, fuller bodies were often seen as a symbol of wealth and fertility, while slimness came to be glamorized in more recent times, partly under the influence of fashion and Hollywood. Increasingly, society is now recognizing health, functionality, and confidence as markers of attractiveness. Strength, posture, and poise are becoming more prized than rigid adherence to beauty templates.

The Psychology Behind the Study

Led by psychologist David I. Perrett and his colleagues, the study set out to explore not just what men and women find attractive in faces, but what they think the opposite sex finds attractive—and whether these beliefs align with reality. They hypothesized a significant mismatch. Specifically, the team believed that men would imagine women desire more masculine male faces than they actually do. Conversely, women were expected to think men preferred more feminine female faces than men truly find appealing.

The researchers also wanted to explore how relationship context might affect these preferences. Would people think different facial traits are more desirable for a short-term fling versus a long-term relationship? Finally, they examined whether personal dissatisfaction with one’s own facial appearance was tied to greater errors in estimating the preferences of the opposite sex.

Building Faces and Testing Perceptions

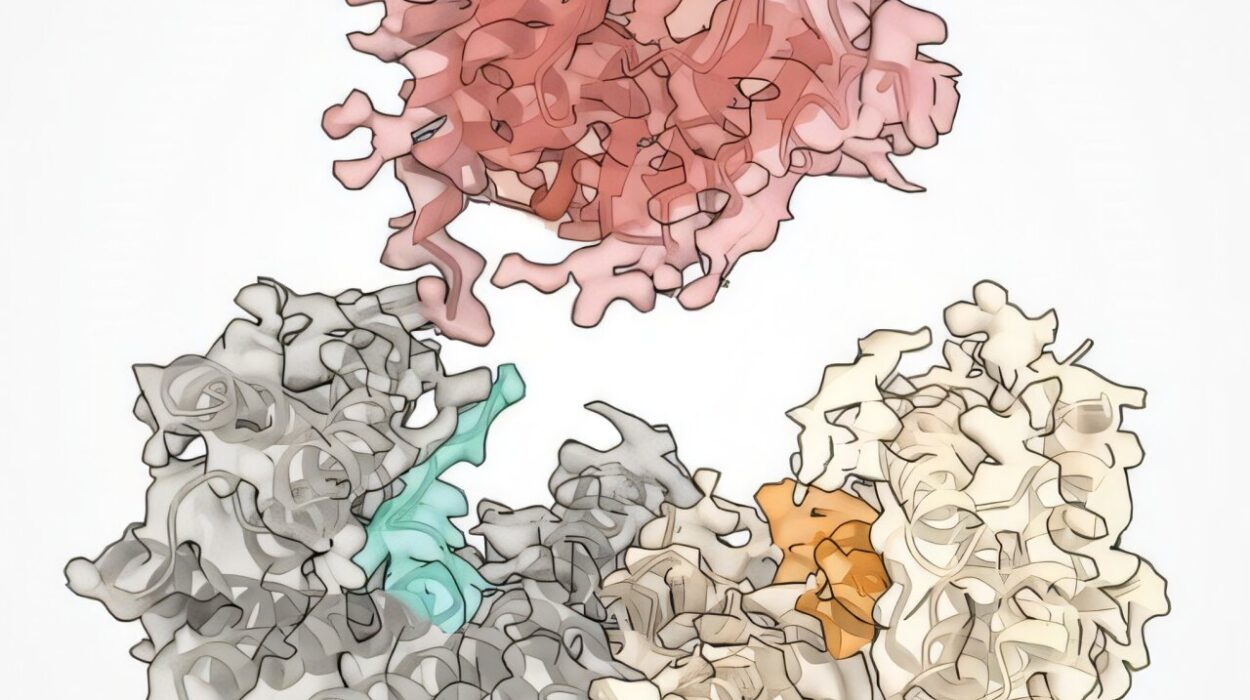

To test these ideas, the team recruited 144 young adults from the U.K., equally split by gender, with an average age of 22. Each participant interacted with a series of 3D face models that could be altered using sliders. Starting from a composite of four different faces for each gender, the researchers created base models that could be manipulated along a spectrum—more masculine or feminine depending on the adjustments.

Participants were asked to make three types of facial alterations. First, they adjusted a face to resemble their own, matching their perceived facial traits. Then, they were asked to manipulate male and female faces to make them maximally attractive to the opposite sex. These attractiveness judgments were made separately for short-term and long-term relationship contexts.

This interactive design allowed the researchers to compare the masculinity or femininity of the face people believed was most attractive to the opposite sex with what those in the opposite sex actually preferred.

The Surprising Results

The findings were striking and consistent. Men significantly overestimated how much facial masculinity women found attractive. When women adjusted male faces to what they found most appealing, the masculinity was toned down compared to the versions created by male participants imagining female preferences.

On the other hand, women overestimated how feminine men wanted female faces to be. The faces women thought would be most desirable to men were more exaggerated in femininity than those men actually selected as most attractive.

These mismatches were more pronounced in the context of short-term relationships. Men assumed that women would prefer a highly masculine face for a casual fling—more so than for a long-term relationship. However, women did not show the same level of variation in their estimates of what men would find attractive in short-term versus long-term contexts.

Moreover, men tended to idealize faces that were more masculine than their own, and women did the same with femininity. This points to a deeper psychological pattern: the more people misjudged what others found attractive, the more likely they were to be dissatisfied with their own appearance.

Self-Doubt and Beauty Myths

The study reveals how the mind distorts the mirror. Misperceptions about attractiveness are not just external guesses—they reflect internal insecurities. If a woman believes men desire hyper-feminine features, and she perceives herself as falling short, dissatisfaction follows. The same holds for men who think women want ultra-masculine features.

Interestingly, the researchers did not directly ask participants whether they were happy with their appearance. Instead, they inferred dissatisfaction based on the gap between the participants’ facial features and the idealized versions they created. Still, the pattern was clear: the bigger the misjudgment of others’ desires, the more likely it was tied to self-image discomfort.

More Than Just a Face

Despite its insights, the study focused narrowly on facial shape—specifically, the masculinity and femininity of facial features. Real-world attraction, of course, is a tapestry woven from countless threads: voice, scent, body language, conversation, shared values, and emotional connection. While appearance certainly plays a role, it is only one factor in romantic chemistry.

Additionally, cultural, social, and personal factors greatly influence preferences. What is deemed attractive in one region or age group may not hold in another. Preferences may also shift over time with life experience, exposure to diversity, and changes in one’s own self-image.

Implications and Reflections

The research by Perrett and colleagues offers more than just an academic look at attraction—it provides a mirror to modern society’s beauty myths and the psychological toll they take. The consistent overestimation of gendered traits reflects not only a misunderstanding of what others want, but also a misunderstanding of how we view ourselves.

As media and technology continue to shape our perceptions of beauty, such studies act as a reminder to question the narratives we internalize. The ideal face may not be as sharply defined as we think, and the pressure to conform to exaggerated standards might do more harm than good.

Confidence, authenticity, and emotional resonance may matter far more than the precise angle of a jawline or the fullness of lips. In the end, understanding what people actually find attractive might help us not only relate better to others but also feel more comfortable in our own skin.