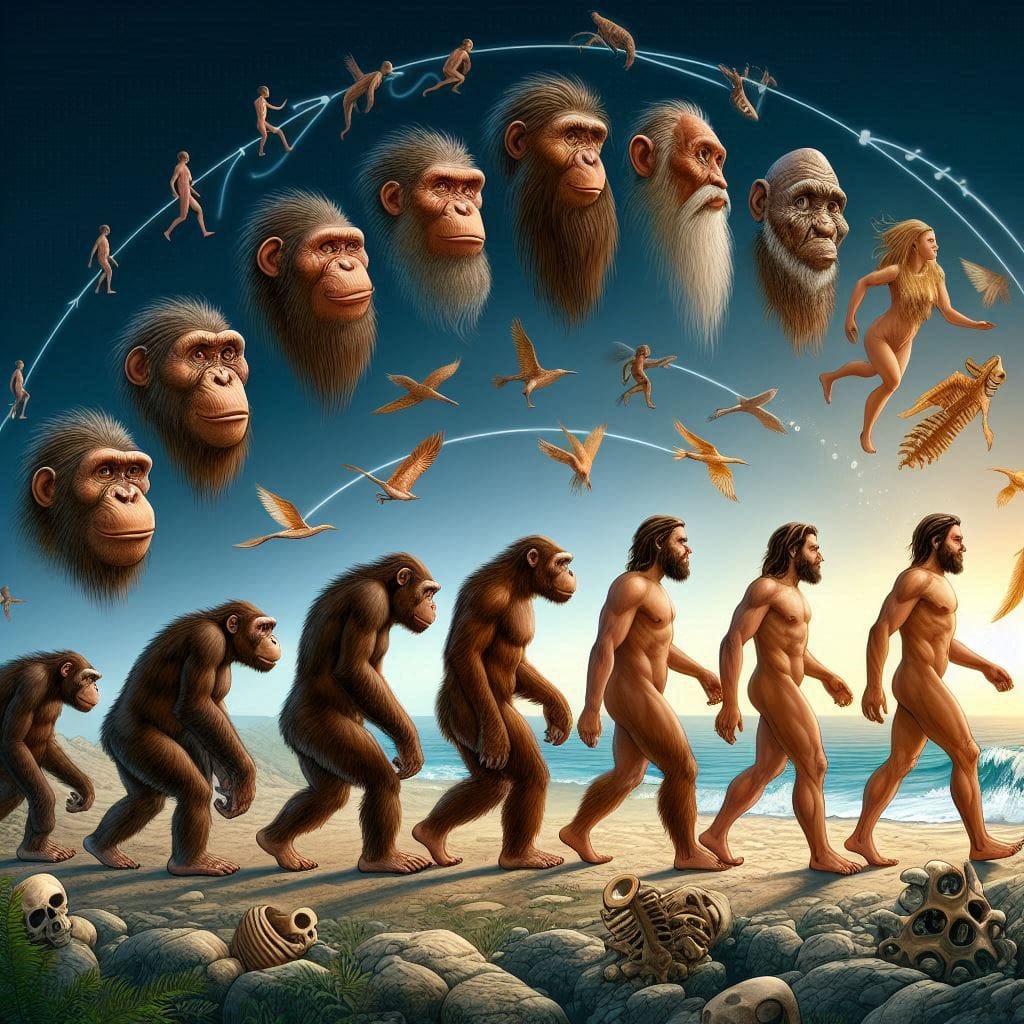

We live in a world that never stands still. Mountains rise and fall. Rivers carve new paths. Oceans shift their currents. And within this ever-changing Earth, life itself dances to an invisible rhythm—the rhythm of evolution. For many people, evolution is something confined to dusty textbooks, fossilized bones, or ancient tales of primordial oceans. We think of dinosaurs turning into birds, or ape-like ancestors walking upright in African savannas. Evolution, to most, is a story of the distant past.

But the truth is far more thrilling. Evolution is not a relic of history. It’s happening all around us, right now, in real time. In the DNA of every living organism, from the simplest microbe to the tallest tree to you and me, the forces of change continue to sculpt life with patient but relentless hands. To understand evolution as a living process, we must look not only backward into prehistory, but also forward—into petri dishes, hospital wards, polluted lakes, and even the human genome.

Evolution is alive. And so is its story.

The Mechanics of Change: How Evolution Works

To understand whether evolution is still happening today, we must revisit what it truly means. At its core, evolution is change in the genetic makeup of populations over time. It’s not about individuals suddenly sprouting wings or growing gills. It’s about tiny shifts in DNA—mutations, gene flows, recombination—that, over generations, reshape how species function, look, and survive.

The main engines driving this process are well known. Mutation provides the raw material—small, often random changes in genetic code. Natural selection filters these mutations, favoring traits that increase survival or reproduction. Genetic drift introduces randomness, especially in small populations, and gene flow moves genes between populations, allowing for the spread of advantageous traits.

This process is continuous. It doesn’t stop once a species is “formed” or “perfected.” Because environments change, predators evolve, food sources shift, diseases emerge. To stay alive, organisms must adapt. Or vanish. That’s the brutal beauty of evolution—it never sleeps.

The Evolution of Microbes: Rapid Fire in Real Time

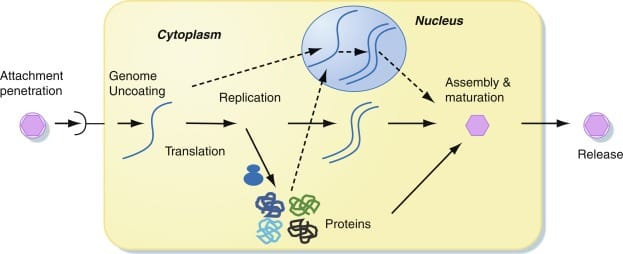

If you want to witness evolution happening before your eyes, you need only look through a microscope. Bacteria, viruses, and other microbes are the fastest-evolving life forms on the planet. Their short generation times and immense population sizes allow them to evolve at speeds that seem almost supernatural.

Consider antibiotic resistance. When Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, it revolutionized medicine. Infections that once meant death were now curable. But within just a few decades, bacteria began to fight back. Some carried mutations that made them immune to the drugs. These survivors reproduced, passing on resistance. Today, antibiotic-resistant bacteria are one of the most serious threats to global health.

The same is true of viruses. The SARS-CoV-2 virus, responsible for COVID-19, evolved before our eyes, with new variants such as Delta and Omicron rapidly sweeping across the globe. Each variant carried mutations that allowed it to spread more effectively or evade immune responses. Evolution wasn’t just something happening in textbooks. It was on the news, in our hospitals, in our lungs.

These examples aren’t isolated. From malaria parasites resisting drugs to crop-destroying fungi adapting to pesticides, the microbial world is in constant flux. Evolution in this realm is not only happening—it’s relentless, adaptive, and often terrifying.

The Wild Adapts: Evolution in Animals and Plants

Beyond the microbial world, evolution marches on in more familiar creatures. Birds, fish, insects, mammals, and even plants are all adapting to the challenges of modern life, many of which are caused by human activity.

Take the peppered moth in England. In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution blackened trees with soot. The dark-colored variant of the moth, once rare, became more common because it was better camouflaged. When air pollution was reduced, lighter moths made a comeback. This classic example of natural selection in action is still studied today—and it’s still ongoing.

Urban environments have become new arenas of evolution. Some birds now sing higher-pitched songs to be heard above city noise. Mice in New York City have evolved digestive systems that help them handle human food. Mosquitoes in London’s underground have formed distinct breeding populations—essentially, they’re evolving into a new species right beneath our feet.

In the oceans, fish species like cod and salmon have been shrinking in size due to overfishing. The larger individuals are removed from the gene pool, leaving behind those that mature earlier at smaller sizes. This isn’t just ecological pressure—it’s evolutionary pressure.

Even plants are responding to our world. Some weeds now resist herbicides. Others bloom earlier due to climate change. In California, mustard plants have evolved shorter stems and smaller leaves to conserve water. Nature is not passive. It fights back, adapts, and survives.

Human Evolution: Are We Still Evolving?

One of the most provocative questions is whether we, Homo sapiens, are still evolving. Many assume that evolution stopped once modern medicine emerged. After all, don’t we now save lives that nature once would have culled? Don’t glasses, surgery, and antibiotics shield us from natural selection?

The reality is more complex—and more fascinating.

Yes, modern medicine and technology have changed the selective pressures we face. But they haven’t eliminated them. Evolution continues, just in subtler, more nuanced ways. For instance, the human genome shows evidence of recent adaptations in the last few thousand years. The ability to digest lactose as an adult, for example, evolved independently in several human populations due to the domestication of dairy animals.

In high-altitude populations like Tibetans and Andeans, genetic mutations allow for more efficient oxygen usage. In areas where malaria is common, genes like the sickle-cell trait have persisted because they offer some protection, despite their risks.

Moreover, sexual selection—who we choose as partners—can influence the genetic direction of future generations. Cultural practices, diet, urbanization, and even stress may have long-term evolutionary consequences.

Studies of human populations show changes in genes related to immune response, metabolism, and brain function. As new technologies like CRISPR and artificial intelligence interface with our biology, some argue we are entering a phase of self-directed evolution—where we may guide our own genetic destiny.

Evolution Under the Microscope: Watching It Happen in Labs

Evolution is no longer just inferred from fossils and ancient bones. In the 20th and 21st centuries, scientists have begun to observe it directly through long-term experiments.

One of the most famous is the E. coli long-term evolution experiment, started by Dr. Richard Lenski in 1988. It has tracked over 75,000 generations of bacteria. Over time, researchers have observed the emergence of new traits, including the ability to metabolize citrate—something these bacteria couldn’t do before. This is evolution, plain and simple.

In the lab, fruit flies evolve resistance to toxins. Mice evolve behavioral changes. Even plants evolve in greenhouses, adapting to drought or altered soil.

These experiments are windows into evolution’s tempo and mode. They show us that even in controlled environments, life changes—often in unexpected ways.

Evolution in Crisis: Extinction or Adaptation?

If evolution is about adaptation, what happens when the pace of environmental change outstrips the ability to evolve? This is the challenge facing many species today.

Climate change is altering habitats at a speed unseen in evolutionary history. Coral reefs bleach. Polar bears starve. Amphibians vanish. Some species are adapting—shifting ranges, changing behaviors—but many are simply disappearing.

The evolutionary arms race is a cruel one. Not all make it. Evolution does not promise survival; it only describes change. If change happens too fast, extinction can be the final outcome.

Yet hope persists. Some corals are evolving heat resistance. Certain insects shift their breeding cycles. Trees migrate up mountains, chasing cooler air. If conservation efforts can buy enough time, evolution may offer a lifeline.

The Genetic Revolution: Evolution Meets Technology

In the 21st century, evolution is entering a new era—one where the tools of genetic engineering blur the lines between natural selection and human intention.

CRISPR technology allows us to edit genes with precision. Scientists have used it to cure genetic diseases in animals, alter crops, and even resurrect extinct genes. Gene drives are being explored to eliminate malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Synthetic biology creates entirely new organisms from designed DNA.

Are we still evolving naturally? Or are we now directing evolution? And what are the ethical, philosophical, and ecological implications?

These are no longer questions for the distant future. They are decisions we face today. Evolution is not just a biological process—it is now a cultural one, deeply interwoven with human values and responsibility.

A Deeper Understanding: Evolution as a Way of Seeing the World

To ask whether evolution is still happening is, in some ways, to miss the point. Evolution is not an event—it is a lens through which to understand life.

It explains why whales have vestigial pelvises. Why birds have feathers. Why humans walk on two legs, speak in language, and build civilizations. It explains the beauty and the brutality of nature. The peacock’s tail and the parasite’s teeth.

It also connects us to all living things. Every gene we carry has a history. Every adaptation is a chapter in the story of survival. We are not separate from evolution—we are its most self-aware product.

To study evolution is to study change, resilience, and creativity. It is to recognize that life is not static, not perfect, but dynamic and unfinished. It is to accept that who we are today is not who we were, and not who we will be.

The Road Ahead: What Comes Next?

As we face a future shaped by climate change, technological disruption, and population pressures, evolution will continue to unfold. Some species will vanish. Others will emerge. Genes will flow, mutate, and recombine in endlessly novel ways.

For humans, the future of evolution may be increasingly self-authored. With the ability to edit our genomes, control reproduction, and engineer life, we face profound questions. What should we change? What should we preserve? Who decides?

But even in a world of gene editing and artificial intelligence, the core principles of evolution remain. Variation. Selection. Inheritance. Time. These forces will still shape the trajectory of life, whether guided by nature or nudged by human hands.

In the end, the answer to whether evolution is still happening today is clear: yes. It is happening in bacteria and birds, in cities and oceans, in our bodies and our technologies. It is the quiet pulse behind every breath of adaptation, every mutation, every change.

And it will continue—as long as life continues.