Most of us carry our lives in silence, appearing composed on the outside while battles rage within. We carry deadlines, arguments, childhood wounds, grief, shame, worry for those we love, and fear for what may come. And somewhere beneath the surface of all this—often beyond our awareness—our brains are working tirelessly, adapting to the storms of stress and trauma that life hurls our way.

Stress is not always a villain. It is an evolutionary gift, a survival mechanism shaped by millions of years. But trauma—intense, overwhelming, and sometimes prolonged—can shake the human brain to its foundations. When the stress system is pushed too far, for too long, something fundamental begins to shift in the architecture of the mind.

Understanding how the brain reacts to stress and trauma is more than a scientific curiosity. It’s a map—a guide to how we suffer, how we heal, and how the human mind fights to protect itself from shattering entirely. And to truly see the story, we must begin not with the pain, but with the brain itself: an organ of astounding power, resilience, and vulnerability.

The Brain’s Architecture of Survival

The human brain is not a single structure. It is a layered and interconnected system of specialized regions that evolved over time. The deepest parts—the brainstem and limbic system—are primitive and fast. They are responsible for instinctive reactions, survival, and emotion. The outer layer—the neocortex—is slower and more sophisticated, allowing us to plan, reflect, and regulate.

When we face stress, especially acute or immediate threats, the brain does not react with reason. It reacts with reflex. The key player in this lightning-fast system is the amygdala, an almond-shaped cluster deep in the temporal lobe. The amygdala acts like a smoke detector: scanning our environment for danger, real or perceived. If it detects a threat, it lights up instantly, sending a signal that something is wrong.

This signal is then passed to the hypothalamus, the control center for the autonomic nervous system. From here, the hypothalamus triggers a cascade of responses—the release of adrenaline, the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, and, if the threat persists, the engagement of the HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis).

Cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone, begins to flow. Heart rate increases. Blood pressure rises. Digestion halts. Muscles tense. The body is now in fight-or-flight mode. You might feel anxiety, restlessness, or a rush of energy. This system is brilliant in short bursts—it can save your life. But what happens when the danger doesn’t go away?

Chronic Stress: When the Alarm Never Stops

In the wild, stress was typically short-lived. A predator appears; you flee or fight; the danger passes. But in modern life, stress is often chronic. The email that never stops. The financial anxiety. The toxic relationship. The trauma that lingers. The nervous system doesn’t always know the difference between a lion and a layoff. And so it remains on high alert.

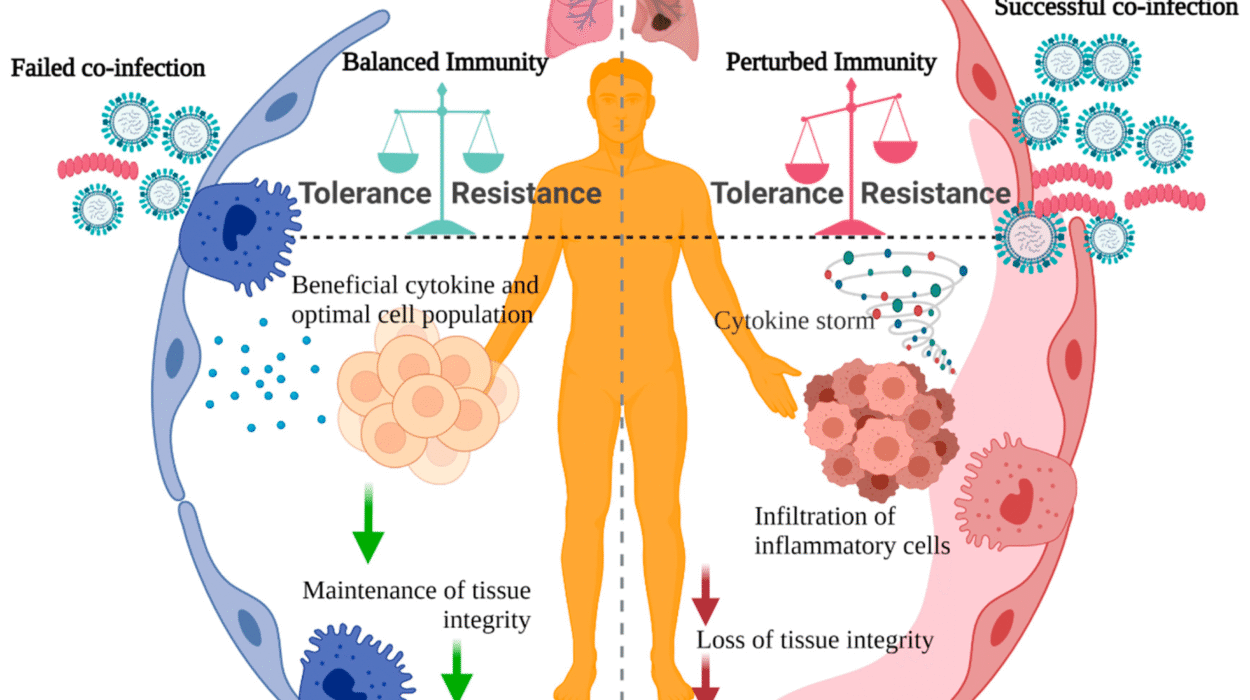

When the stress system is activated over and over without relief, the consequences ripple through the brain. The amygdala, the brain’s threat detector, begins to grow more sensitive, more reactive. It can become overactive, leading to hypervigilance and anxiety. Small triggers—like a sudden sound or an angry tone—can feel like danger alarms.

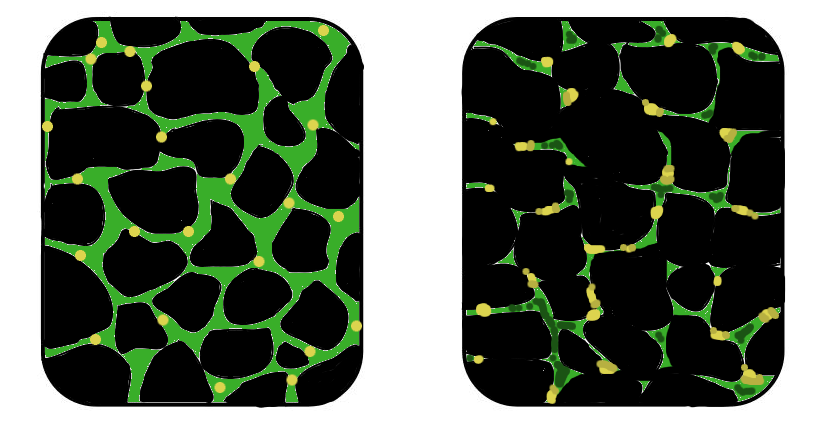

Meanwhile, the hippocampus—another part of the limbic system, responsible for memory and spatial navigation—begins to shrink. The hippocampus helps us contextualize threats and distinguish the past from the present. But under chronic stress, its neurons wither. Memories become fragmented. Trauma can feel ever-present, as if it’s still happening now.

Worst of all, the prefrontal cortex—the rational, thinking brain—starts to weaken. This is the part of the brain that helps us regulate emotions, suppress impulses, and make decisions. Chronic stress impairs its function. You might feel foggy, irritable, or unable to concentrate. Emotional control fades. You lash out. You break down. You freeze.

This triad—an overactive amygdala, a shrinking hippocampus, and a compromised prefrontal cortex—can become the new normal for someone living under long-term stress. It’s a dangerous cycle, not only emotionally but physically. Chronic stress has been linked to heart disease, diabetes, and immune dysfunction. The brain’s fire alarm becomes a slow-burning fuse.

Trauma: The Broken Compass

Trauma is not just stress magnified. It is stress that overwhelms the nervous system’s capacity to cope. It can come from a single catastrophic event—like war, abuse, rape, or disaster—or from smaller, cumulative experiences, such as childhood neglect or long-term emotional abuse. Trauma sears itself into the brain differently than ordinary experience.

One of the cruelest effects of trauma is how it rewires the sense of self. People who have been traumatized often describe a feeling of disconnection—not only from others but from themselves. Their body doesn’t feel like home anymore. They may experience dissociation, numbness, or flashbacks. These are not mental weaknesses. They are neurological survival strategies.

The brain’s memory systems are heavily affected by trauma. Normally, memories are processed in the hippocampus and stored with context—what happened, when, and how. But during trauma, the prefrontal cortex can go offline, and the hippocampus may fail to organize the memory correctly. Instead, fragments of sensation, sound, or emotion are stored directly in the amygdala—raw, unfiltered, and without time stamps.

This is why trauma can come back suddenly and violently. A sound, a smell, or a phrase can trigger a flashback. The brain doesn’t recall the memory—it relives it. The body reacts as if the event is happening again. The rational mind knows you’re safe, but the emotional brain does not. Trauma locks the nervous system in a loop of unfinished alarms.

The Child’s Brain Under Siege

Children are especially vulnerable to the effects of trauma. Their brains are still forming, their stress systems still calibrating. When a child experiences abuse, neglect, or chaos, the entire architecture of the brain can be altered. This is known as developmental trauma.

In children, chronic stress can delay the growth of the prefrontal cortex, impair memory formation, and create permanent overactivation in the amygdala. These children may struggle in school, lash out, or withdraw. They may be misdiagnosed with ADHD or conduct disorders. But underneath the behavior is often a brain that has learned that the world is not safe.

Attachment theory provides further insight. When caregivers are unreliable or threatening, the child learns that love and safety are conditional. The nervous system becomes dysregulated. Trust becomes a risk. And without intervention, these neural patterns can persist into adulthood, shaping relationships, identity, and emotional resilience.

This is not destiny, but it is gravity. Trauma leaves fingerprints on the brain. But even the deepest imprints are not unchangeable.

Healing the Injured Brain

The brain’s most remarkable quality is its neuroplasticity—the ability to change, rewire, and heal. Just as stress and trauma shape the brain, so too can recovery. But healing is not just about “getting over it.” It is about creating new neural pathways, new patterns of safety, and a new relationship with the body and mind.

One of the most important elements of healing is safety. Before any cognitive processing can occur, the nervous system must feel safe. For some, this begins with therapy—especially trauma-informed therapy such as EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), somatic experiencing, or cognitive-behavioral therapy. These methods help reconnect the fragmented parts of memory, restore a sense of agency, and calm the hyperactive alarm system.

Mindfulness and meditation have also been shown to reverse some of the effects of chronic stress. Regular mindfulness practice strengthens the prefrontal cortex, reduces amygdala activation, and improves emotional regulation. Breathwork and grounding exercises help bring awareness back into the body—a body that trauma often teaches us to abandon.

Social connection is perhaps the most powerful medicine of all. Isolation fuels trauma; connection soothes it. Positive, secure relationships help reset the nervous system, teaching the brain that not all intimacy is dangerous. For trauma survivors, trust must often be rebuilt slowly, one moment at a time.

Sleep, nutrition, movement, and creative expression also play vital roles. The brain is not an isolated machine; it is a living ecosystem. Healing must be holistic.

The Epigenetics of Stress and Inherited Trauma

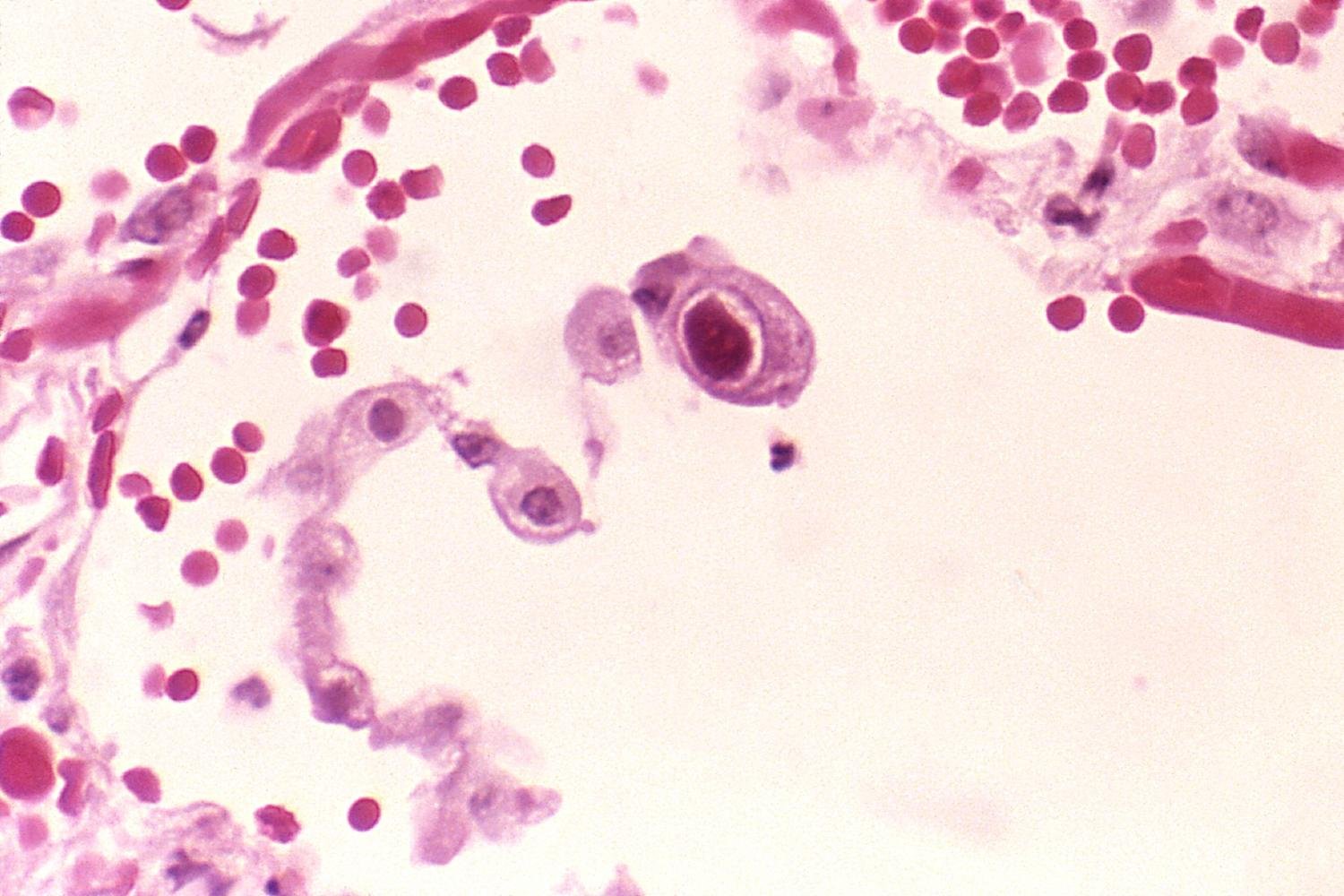

In recent years, scientists have discovered that trauma doesn’t just live in memory—it can live in our genes. This does not mean trauma rewrites our DNA, but it can influence which genes are expressed or silenced. This field is known as epigenetics.

Studies in both humans and animals show that trauma can cause epigenetic changes that are passed down through generations. For example, children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, or survivors of famine, war, and slavery, show altered stress responses even if they never experienced the trauma themselves.

The mechanism involves methylation—tiny chemical tags that attach to DNA and affect gene expression. Trauma can increase methylation in genes related to stress regulation, such as those involved in cortisol processing. These tags can influence how a person responds to stress decades later.

This discovery has profound implications. It means that healing from trauma is not just personal—it is ancestral. To heal oneself is, in some way, to change the future.

The Brain’s Resilience: A Story of Hope

For all its fragility, the brain is also resilient beyond measure. Survivors of profound trauma can, and do, recover. Soldiers, abuse survivors, refugees, and those who have endured the unimaginable often find strength they never knew they had. The brain does not forget trauma—but it can learn new responses to it.

Post-traumatic growth is real. Some people, after healing, report deeper empathy, a stronger sense of purpose, and a greater appreciation for life. The cracks in their psyche do not disappear, but light begins to shine through them. The human brain, when given space, connection, and support, can transform suffering into wisdom.

Understanding how the brain reacts to stress and trauma is not only a scientific pursuit—it is a deeply human one. It reminds us that we are wired not just to survive, but to adapt. Not just to endure pain, but to transform it.

The Science of Compassion

One final note must be made: understanding trauma also demands compassion. When someone lashes out, shuts down, or withdraws, we must remember that their brain may be fighting a war we cannot see. When we judge others—or ourselves—for not “getting over it,” we ignore the invisible architecture of pain.

Compassion is not weakness. It is neuroscience. The brain calms in the presence of safety, of empathy, of love. The most healing act we can offer—to ourselves or to others—is not to fix the pain, but to witness it without judgment.

In the end, the brain’s reaction to stress and trauma is a story not just of breakdown but of possibility. Of fire and ash, yes—but also of rebirth.