Osteoporosis is often called the “silent thief,” and the metaphor is painfully accurate. For years, sometimes decades, it lurks unnoticed, quietly weakening bones while showing no outward signs. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, a fracture occurs—a broken hip after a minor fall, a collapsed vertebra while bending forward, or a wrist fracture during daily activities. These are not just random accidents; they are the visible consequences of a disease that slowly erodes the very framework that holds us upright.

Health is rarely something we think about until it falters. Bones, in particular, are taken for granted. They are solid, dependable, and unyielding—or so we believe. Yet bones are living tissues, constantly being broken down and rebuilt. When this balance is disrupted, and bone loss outpaces bone formation, osteoporosis emerges. It is not simply a matter of aging or frailty; it is a medical condition with biological, lifestyle, and genetic roots.

To understand osteoporosis fully is to understand not only what weakens bones but also what strengthens them—how choices, treatments, and awareness can restore resilience to our skeletal system. This article delves into the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments of osteoporosis, weaving together science and human experience to reveal how this condition impacts millions and how it can be managed.

What Is Osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis, derived from the Greek words osteo (bone) and poros (passage or pore), literally means “porous bone.” It describes a condition where bones become less dense, fragile, and more susceptible to fractures.

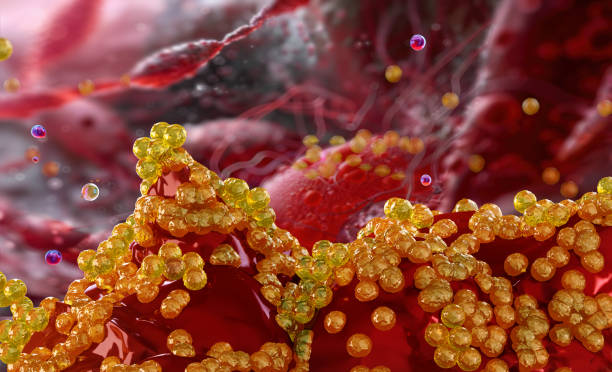

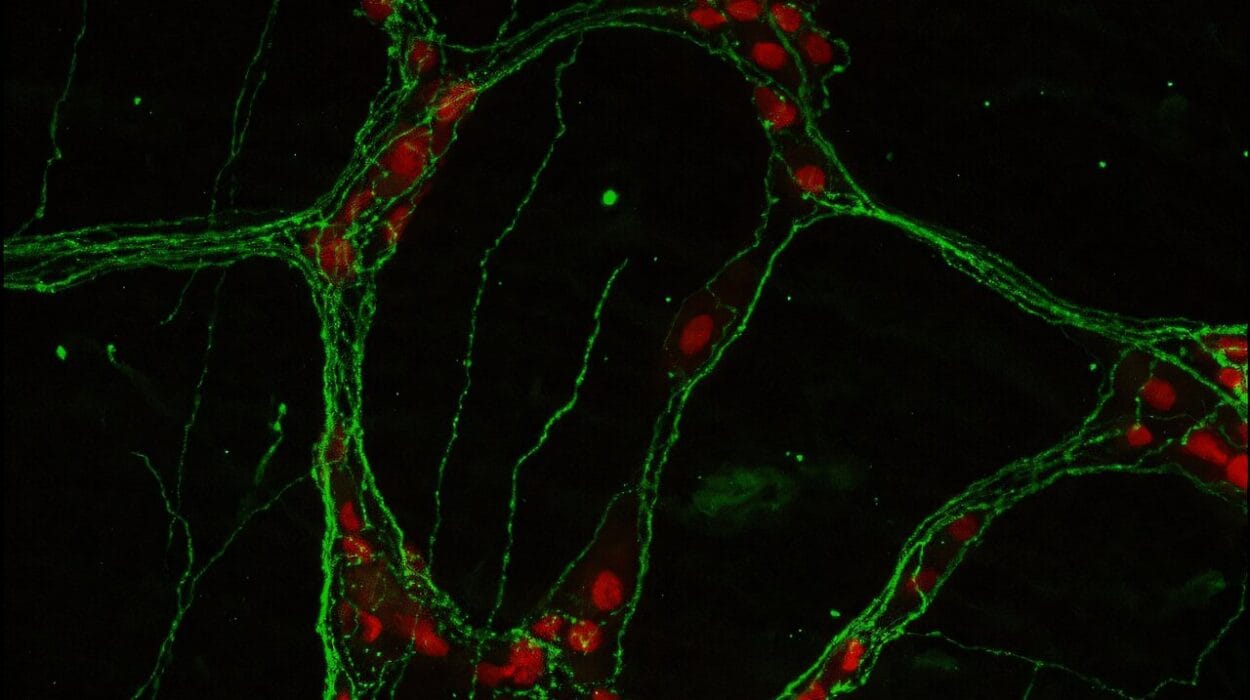

In healthy individuals, bone is dynamic: old bone tissue is continuously broken down by cells called osteoclasts and replaced by new bone tissue built by osteoblasts. This remodeling process ensures that bones remain strong and can adapt to stress. In osteoporosis, the remodeling process becomes imbalanced. Bone breakdown occurs faster than bone formation, resulting in decreased bone mass and structural deterioration.

The consequence is that bones lose their internal architecture—the delicate latticework that gives them strength. Under a microscope, osteoporotic bone looks like a honeycomb with widened holes, making it less able to withstand normal forces. This deterioration increases the risk of fractures, even with minimal trauma.

The Causes of Osteoporosis

The development of osteoporosis is complex, influenced by an interplay of biological, genetic, hormonal, and lifestyle factors. While aging is the strongest risk factor, osteoporosis is not simply an inevitable part of growing old. Understanding its causes sheds light on how it can be prevented and managed.

Aging and Bone Remodeling

As we age, the body’s ability to regenerate bone naturally declines. Peak bone mass is typically reached by the late 20s or early 30s. After that, the balance gradually tips toward bone loss. For women, menopause accelerates this decline due to a sharp drop in estrogen levels, a hormone critical for maintaining bone density.

Hormonal Factors

Hormones play a central role in bone health. Estrogen in women and testosterone in men both help regulate bone turnover. When these hormones fall—through menopause, aging, or medical conditions—the protective effect on bones diminishes.

Other hormonal imbalances can also contribute. Overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism), overproduction of parathyroid hormone (hyperparathyroidism), or excess cortisol from conditions like Cushing’s syndrome can all increase bone resorption, leaving bones fragile.

Genetic Predisposition

Genetics strongly influence peak bone mass and fracture risk. Individuals with a family history of osteoporosis or fractures are more likely to develop the disease. Genetic variations affect how efficiently bones build during youth and how rapidly they decline with age.

Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

Lifestyle choices are among the most modifiable causes of osteoporosis. Poor nutrition—especially diets low in calcium, vitamin D, and protein—deprives bones of essential building blocks. Sedentary behavior weakens bones, since weight-bearing activity stimulates bone growth.

Smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and chronic use of certain medications such as glucocorticoids, anticonvulsants, or chemotherapy agents further accelerate bone loss.

Medical Conditions

Osteoporosis can also be secondary to other health conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease. These conditions may impair nutrient absorption, disrupt hormone regulation, or trigger inflammation that damages bone tissue.

The Symptoms of Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is often called a “silent disease” because it typically shows no symptoms until a fracture occurs. Unlike conditions that cause pain, swelling, or fever, osteoporosis progresses quietly. However, certain signs can reveal its presence over time.

Fractures: The Defining Symptom

The most significant and often first noticeable symptom of osteoporosis is a fracture. These fractures commonly occur in the hip, spine, and wrist. Unlike fractures from major accidents, osteoporotic fractures can happen with minimal trauma—such as falling from standing height or even bending over.

Spinal Changes

Vertebral fractures are particularly telling. They may occur without obvious injury and can cause sudden or gradual back pain. Over time, multiple vertebral fractures lead to height loss and a stooped posture known as kyphosis, sometimes referred to as a “dowager’s hump.”

Subtle Warning Signs

Some people may experience bone pain or tenderness, though this is less common. More often, the warning signs are subtle: clothes fitting differently due to height loss, chronic back discomfort, or a noticeable change in body shape.

Because osteoporosis can remain hidden until damage is done, early detection through screening is crucial, especially for individuals at higher risk.

Diagnosing Osteoporosis

Detecting osteoporosis before fractures occur is one of the greatest challenges in medicine. Thankfully, advancements in diagnostic tools have made it possible to measure bone density and assess fracture risk accurately.

Bone Mineral Density Testing

The gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis is a bone mineral density (BMD) test using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA or DXA). This painless scan measures bone density in the hip and spine, providing a T-score that compares a patient’s bone density to that of a healthy young adult.

- A T-score of -1.0 or above is considered normal.

- Between -1.0 and -2.5 indicates osteopenia (low bone mass but not osteoporosis).

- -2.5 or lower indicates osteoporosis.

Clinical Risk Assessment

Tools such as the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment Tool) combine bone density results with other risk factors—age, sex, smoking, alcohol use, and family history—to estimate the 10-year probability of fractures. This helps doctors decide when to begin treatment, even for patients without severely low BMD scores.

Imaging and Laboratory Tests

X-rays can reveal fractures or spinal deformities but are not sensitive enough to detect early bone loss. Blood and urine tests may be used to identify underlying causes, such as vitamin D deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, or other metabolic conditions.

Early diagnosis allows for intervention before debilitating fractures occur, making screening vital for postmenopausal women, older men, and anyone with risk factors.

Treatment of Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is treatable, though not always curable. The goal of treatment is to prevent fractures, strengthen bones, and improve quality of life. Effective management combines medications, lifestyle changes, and supportive care.

Medications

Several classes of medications are used to treat osteoporosis, each working in different ways to slow bone loss or stimulate bone growth.

- Bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, zoledronic acid) are the most commonly prescribed drugs. They slow bone resorption, helping bones retain density.

- Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs) (such as raloxifene) mimic estrogen’s protective effect on bones without some of the risks associated with hormone therapy.

- Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) may be used for postmenopausal women but carries risks, including cardiovascular disease and certain cancers.

- Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody, reduces bone breakdown by targeting a protein involved in bone resorption.

- Anabolic agents (teriparatide, abaloparatide, romosozumab) stimulate bone formation and are used for patients at very high risk of fractures.

Medication choice depends on age, sex, fracture history, risk factors, and tolerance. Treatments often continue for years, with periodic reassessment.

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle changes form the cornerstone of osteoporosis management and prevention. Nutrition is essential: adequate calcium and vitamin D intake supports bone strength. Weight-bearing exercises like walking, dancing, or resistance training stimulate bone growth and improve balance, reducing fall risk.

Avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol also help protect bone health. For older adults, fall prevention—through home safety, vision correction, and balance training—reduces the risk of fractures.

Pain and Fracture Management

For those who have already sustained fractures, treatment includes pain relief, physical therapy, and sometimes surgical interventions. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are procedures used to stabilize spinal fractures. Hip fractures may require surgical repair or replacement.

Rehabilitation is critical, focusing not only on healing but also on restoring independence and confidence.

Living with Osteoporosis

A diagnosis of osteoporosis can be frightening, but it is not a life sentence of fragility. With modern treatments and lifestyle adaptations, many people with osteoporosis continue to live active, fulfilling lives.

Emotional health plays a vital role. The fear of falling or fracturing can lead to social withdrawal and decreased activity, which ironically worsens bone health. Support groups, counseling, and education empower patients to manage their condition without succumbing to fear.

Living with osteoporosis is about more than taking medication—it’s about building resilience, nurturing the body through diet and exercise, and maintaining hope and confidence in daily life.

Prevention: The First Line of Defense

Because osteoporosis develops silently, prevention is the most powerful strategy. Building strong bones during youth is crucial, since higher peak bone mass reduces the risk of osteoporosis later in life.

Children and adolescents benefit from calcium-rich diets, vitamin D from sunlight or supplements, and active play. In adulthood, maintaining these habits becomes even more critical, as bone mass gradually declines.

Public health initiatives that promote nutrition, exercise, and smoking cessation are essential in reducing the global burden of osteoporosis. Awareness campaigns encourage regular screening for at-risk groups, ensuring early detection and timely treatment.

The Future of Osteoporosis Care

Medical science continues to advance, offering hope for more effective treatments. Researchers are exploring gene therapies, advanced biologics, and novel medications that not only prevent bone loss but also restore bone architecture. Personalized medicine, guided by genetic profiling and advanced imaging, may one day tailor osteoporosis care to each individual’s unique biology.

Technology also offers tools for prevention: smartphone apps track calcium intake and exercise, wearable devices monitor fall risk, and artificial intelligence may soon predict fractures before they occur.

The future of osteoporosis care lies not only in stronger medicines but also in stronger awareness—a society that values bone health as a fundamental aspect of well-being.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Strength

Osteoporosis may steal silently, but knowledge restores power. Understanding its causes, recognizing its symptoms, and embracing prevention and treatment can transform the story of fragility into one of resilience.

Bones may weaken, but human determination remains strong. With science, lifestyle choices, and compassion working together, osteoporosis does not have to mean surrender—it can be the beginning of a conscious, empowered journey toward strength, stability, and life lived fully upright.