Stress is one of the most common words in modern life. We hear it everywhere—at workplaces, schools, hospitals, and even in casual conversations. “I’m stressed out” has become as ordinary as saying “I’m tired.” But behind this everyday expression lies a profound biological and psychological reality. Stress is not simply a fleeting emotion; it is a powerful force that shapes how our bodies and minds function. While short bursts of stress can be helpful—giving us energy and focus in emergencies—chronic stress is a different story. When stress becomes constant, it transforms from a survival mechanism into a silent destroyer, laying the groundwork for chronic illnesses that can last a lifetime.

Understanding how stress contributes to chronic illness is essential not only for medicine but also for our personal lives. It helps explain why so many modern health crises—heart disease, diabetes, depression, autoimmune disorders, and even cancer—are linked not just to diet, genetics, or lifestyle, but also to the unrelenting pressures we experience in our daily lives. Stress is the hidden thread woven through much of human suffering, yet it is also something we have the power to change.

The Biology of Stress: A System Designed for Survival

To understand the connection between stress and illness, we must first look at how stress works in the body. Stress is essentially the body’s alarm system, designed to keep us alive in dangerous situations. Thousands of years ago, when our ancestors faced predators, their survival depended on this system.

When a threat is perceived—whether it’s a lion in the grass or an overflowing inbox—the brain’s hypothalamus triggers a cascade of signals to the adrenal glands, which release stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. This “fight-or-flight” response increases heart rate, raises blood pressure, sharpens focus, and redirects energy toward immediate survival. Muscles tense, breathing quickens, and glucose floods the bloodstream to fuel rapid action.

In short doses, this system is brilliant. It saves lives. But it was never meant to be switched on all the time. Chronic stress is what happens when the body keeps hitting the panic button, day after day, without returning to a state of rest and balance. And this is where the trouble begins.

When the Alarm Never Turns Off

Imagine living in a house where the fire alarm blares constantly, even when there’s no fire. At first, you pay attention. But over time, the sound becomes part of the background, disrupting sleep, fraying your nerves, and damaging the structure of the house itself. Chronic stress works the same way—it keeps the body’s systems activated until they start to wear down.

The constant release of cortisol and other stress hormones disrupts nearly every system in the body. The cardiovascular system is strained, the immune system becomes confused, digestion falters, and even the brain’s wiring begins to change. Instead of protecting us, stress becomes toxic, leaving us more vulnerable to disease.

The Heart Under Pressure: Stress and Cardiovascular Disease

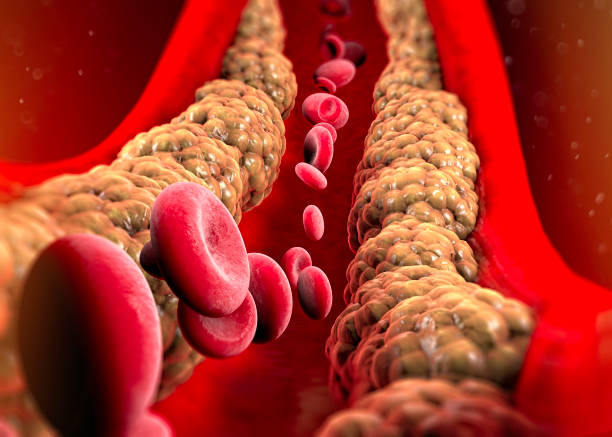

One of the clearest links between stress and chronic illness lies in cardiovascular health. Under stress, blood pressure rises, the heart beats faster, and blood vessels constrict. In the short term, this prepares the body for action. But in the long run, these changes damage the cardiovascular system.

Chronic stress contributes to hypertension, which is a leading risk factor for stroke and heart attack. High levels of cortisol also promote the buildup of plaque in arteries, a process known as atherosclerosis. Moreover, stress can trigger inflammation in blood vessels, making them less flexible and more prone to damage.

Emotional stress has even been shown to precipitate “broken heart syndrome” (takotsubo cardiomyopathy), where the heart temporarily weakens in response to extreme emotional distress. This illustrates how closely our emotional lives are tied to the health of our most vital organ.

Stress and the Immune System: A Double-Edged Sword

The immune system is designed to protect us from infections and heal injuries. But under chronic stress, this finely tuned system begins to malfunction. In the short term, stress can suppress immune activity, making us more susceptible to infections like colds or flu. Over the long term, however, stress may drive the immune system into overdrive, contributing to chronic inflammation.

Chronic inflammation is now recognized as a key player in many illnesses, from diabetes and cancer to Alzheimer’s disease and autoimmune disorders. In autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues, and stress is often a trigger for flare-ups.

This paradox—where stress both weakens and overstimulates the immune system—highlights the complexity of its role in chronic disease. It is not just about lowering defenses; it is about creating chaos in the body’s protective systems.

The Brain on Stress: Mental Health and Neurological Disorders

Stress is not confined to the body; it reshapes the brain itself. Cortisol affects areas like the hippocampus, which is crucial for memory and learning. Prolonged stress can shrink hippocampal neurons, impairing memory and increasing the risk of dementia. It also alters the amygdala, the brain’s fear center, heightening anxiety and emotional reactivity.

The link between stress and mental illness is undeniable. Chronic stress increases the risk of depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and even schizophrenia. It alters neurotransmitter systems, reduces serotonin availability, and affects the brain’s reward circuitry, leading to an inability to experience pleasure.

Even beyond mental illness, stress contributes to cognitive decline. Studies show that people under chronic stress are more likely to develop age-related cognitive impairments and are at greater risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Stress hormones accelerate brain aging, reducing both structure and function over time.

Metabolism in Disarray: Stress and Diabetes

Stress also wreaks havoc on metabolism. Cortisol stimulates the release of glucose into the bloodstream, ensuring energy is available during emergencies. But when stress is constant, this glucose surge becomes harmful. Blood sugar remains elevated, insulin sensitivity decreases, and over time, this contributes to type 2 diabetes.

Furthermore, stress often drives unhealthy behaviors such as overeating, cravings for high-fat and sugary foods, reduced physical activity, and poor sleep. These lifestyle patterns compound the metabolic strain, fueling obesity and insulin resistance.

Thus, stress does not merely accompany diabetes—it actively participates in its development and progression.

The Gut-Brain Connection: Stress and Digestive Disorders

The gut and brain are intimately linked through the vagus nerve and a vast network of neurons known as the enteric nervous system. Stress disrupts this gut-brain axis, altering digestion, absorption, and even the composition of gut microbiota.

People under chronic stress frequently suffer from conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), acid reflux, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Cortisol changes gut motility, increases stomach acid, and weakens the protective lining of the intestines, leading to discomfort and inflammation.

Emerging research shows that stress-induced changes in gut microbiota may also affect mental health, creating a vicious cycle where stress disrupts the gut, and the gut in turn worsens stress and mood disorders.

Stress and Cancer: A Complex Relationship

The connection between stress and cancer is one of the most debated areas of research. While stress alone does not directly cause cancer, it creates an internal environment that may promote its development and progression.

Chronic stress weakens immune surveillance, making it harder for the body to detect and destroy abnormal cells before they turn malignant. Stress hormones also promote angiogenesis (the growth of new blood vessels), which tumors exploit to fuel their growth. Moreover, stress can accelerate metastasis by making it easier for cancer cells to invade tissues and spread.

Patients with cancer who experience high levels of stress often have worse outcomes, not only because of biological changes but also because stress can interfere with treatment adherence, recovery, and overall resilience.

From Coping to Collapse: The Role of Behavior

Stress does not only affect health through biology; it also influences behavior. When stressed, people often turn to coping mechanisms that harm long-term health: smoking, drinking, overeating, or withdrawing from social support. These behaviors compound the biological effects of stress, creating a feedback loop that deepens illness.

For example, stress-related overeating leads to obesity, which in turn worsens stress and raises the risk of heart disease and diabetes. Alcohol may provide temporary relief but damages the liver, disrupts sleep, and increases cancer risk. Social withdrawal reduces emotional support, which is vital for both mental and physical recovery.

In this way, stress shapes not just our physiology but also the choices that determine our health trajectory.

The Epigenetic Shadow of Stress

One of the most fascinating discoveries in recent decades is how stress influences our genes—not by changing DNA sequences but by altering how genes are expressed. This field, known as epigenetics, shows that chronic stress can “switch on” genes associated with inflammation, depression, or metabolic disorders.

These epigenetic changes may even be passed from parents to children, meaning that the effects of stress ripple across generations. Children of parents who experienced extreme trauma often show higher vulnerability to stress-related illnesses, illustrating how deeply stress imprints itself on human biology.

Healing from Stress: The Science of Resilience

If stress is so deeply tied to chronic illness, what hope do we have? The answer lies in resilience—the body’s ability to recover, adapt, and thrive even under pressure.

Resilience is not the absence of stress but the capacity to navigate it without breaking down. Practices like mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and deep breathing activate the body’s relaxation response, lowering cortisol and restoring balance. Exercise, too, is a powerful antidote, reducing stress hormones while boosting mood and brain health.

Social connection is another buffer. Strong relationships reduce the physiological impact of stress and promote healing. Likewise, adequate sleep and balanced nutrition strengthen the body’s resilience, equipping it to handle life’s inevitable challenges.

Rethinking Stress in Modern Life

The modern world is uniquely stressful. Unlike our ancestors, we rarely face physical predators, but we live with constant psychological threats: deadlines, financial worries, traffic, social media pressures, and global uncertainties. Our stress response, designed for short-term emergencies, is now triggered by long-term anxieties.

The challenge is not to eliminate stress altogether—that would be impossible. Instead, we must learn to manage it, transform it, and sometimes even harness it for growth. Stress, after all, is also the force that drives adaptation and resilience. It is the tension that builds muscles, the challenge that sharpens skills, the pressure that forges strength. But only when balanced with recovery does stress become a teacher instead of a tyrant.

Conclusion: The Hidden Path to Wellness

Stress is not just an emotional burden; it is a biological force with the power to shape our health for decades. Left unchecked, it contributes to some of the most devastating chronic illnesses of our time—heart disease, diabetes, depression, autoimmune disorders, and even cancer. It reshapes our brains, alters our genes, disrupts our immune systems, and changes the very way we live.

But the story of stress is not only one of destruction. It is also a story of possibility. By understanding how stress works, we gain the tools to counteract it. Through lifestyle choices, social support, and mindfulness, we can protect our bodies and minds. By reshaping our relationship with stress, we can transform it from a silent killer into a source of strength.

Ultimately, the way we respond to stress may be one of the most important determinants of our health and longevity. The power to heal is not only in medicine but also in how we breathe, how we connect, and how we choose to live each day.