Viruses have shaped human history in ways that no other disease-causing agent has. While the origins of pandemics reach back centuries, it is in the modern era—within the past century—that viruses have caused some of the most devastating and transformative events in human history. HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, and COVID-19, the novel coronavirus responsible for the ongoing global pandemic, represent two of the most significant viral outbreaks to affect the world. Each of these viruses has not only caused untold suffering but also driven scientific, medical, and social change. This article explores the impact of these two viruses and how they, along with other viruses, have altered the course of history.

The Arrival of HIV: The Virus That Redefined a Generation

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), identified in the early 1980s, has since become one of the most destructive viruses in human history. The discovery of HIV marked the beginning of the AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) epidemic, which would ravage millions of lives and cast a long shadow over the global population. Unlike previous pandemics, HIV was a disease that initially affected specific populations, particularly gay men, intravenous drug users, and people in sub-Saharan Africa. It was not until much later that scientists fully understood the virus’s devastating effects on the immune system.

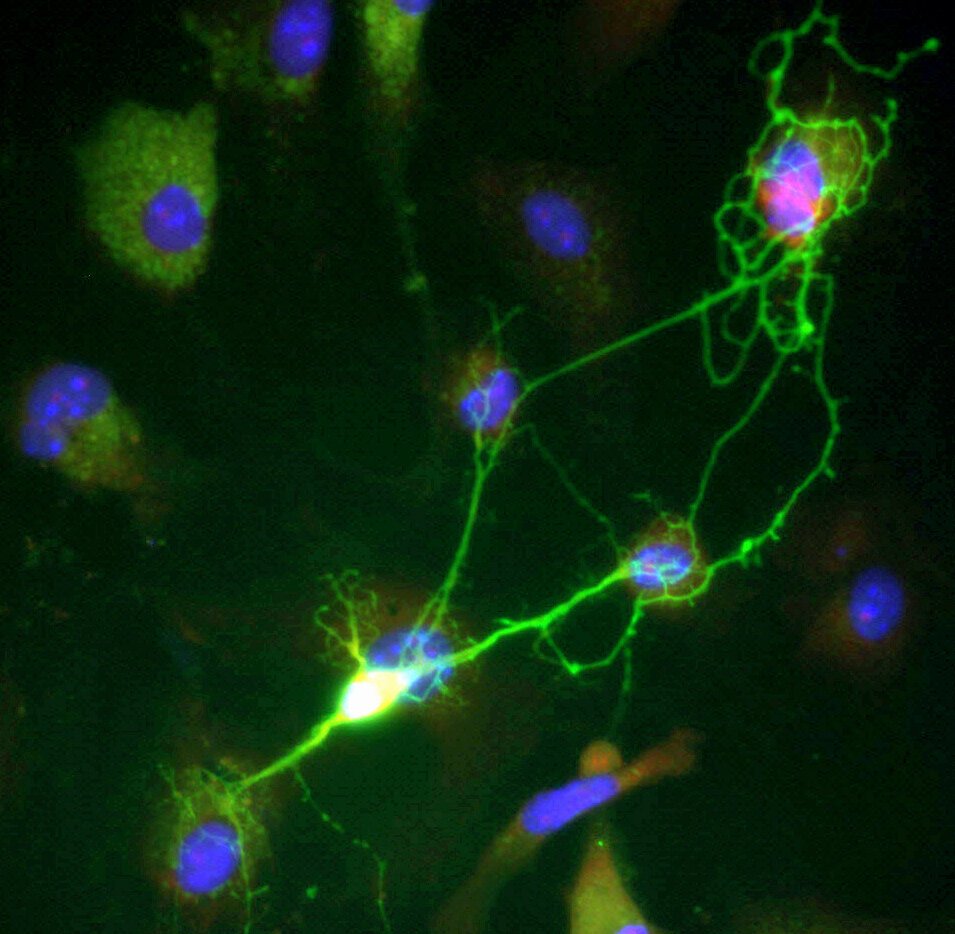

HIV is a retrovirus, which means it attacks the body’s immune system by targeting CD4 cells—critical white blood cells that help protect the body from infections. Once inside the body, HIV hijacks these cells and replicates, ultimately weakening the immune system until the body can no longer fend off common infections. Without effective treatment, HIV leads to AIDS, a condition in which the immune system is severely compromised.

In the early years of the epidemic, there was little understanding of the virus, and treatment options were nonexistent. Fear and stigma ran rampant, particularly against the LGBTQ+ community, intravenous drug users, and people living with HIV in general. By the mid-1980s, thousands of people were dying from AIDS-related illnesses, but the virus was still mysterious. It wasn’t until 1983, when researchers at the Pasteur Institute in France discovered the virus, that the world began to take notice of the disease.

By the time the first antiretroviral drugs were developed in the 1990s, HIV had already claimed millions of lives globally. The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the mid-1990s marked a turning point in the fight against HIV. Though it was not a cure, HAART drastically improved the prognosis for those living with HIV, turning it from a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition for many. Today, with proper treatment, people living with HIV can live long, healthy lives.

Despite this progress, the fight against HIV/AIDS continues. Globally, over 38 million people are living with HIV, and while new infections have decreased in some regions, they remain a major public health concern, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. The ongoing research for a cure and vaccine, as well as the efforts to combat the social stigma surrounding the virus, continues to shape how we understand HIV and its far-reaching effects on society.

The Rise of H1N1: The Pandemic That Nearly Wasn’t

Before COVID-19 captured the world’s attention, the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009 served as a reminder of how quickly a virus could spread across the globe and disrupt daily life. Known colloquially as the “swine flu,” this particular strain of H1N1 was a reassortment of human, swine, and avian influenza viruses, creating a novel strain that was capable of spreading rapidly from person to person.

The outbreak began in Mexico in the spring of 2009, and within months, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a global pandemic. Unlike previous influenza pandemics, H1N1 predominantly affected younger populations, with a greater impact on children, young adults, and pregnant women, in contrast to the elderly, who are typically more susceptible to flu viruses. The H1N1 virus spread quickly around the world, causing widespread fear, but the overall fatality rate remained relatively low, with an estimated 151,700–575,400 deaths globally.

Despite its global spread and high transmission rates, H1N1 did not reach the catastrophic proportions of other pandemics in history, such as the 1918 Spanish flu. Much of this can be attributed to the rapid development of a vaccine, which became widely available within six months of the pandemic’s onset. The swift response by the scientific community, the accessibility of antiviral drugs, and public health measures helped to contain the virus and mitigate its impact.

The H1N1 pandemic serves as a cautionary tale: while the virus was not as deadly as initially feared, the world was given a glimpse of how vulnerable humanity is to infectious diseases. The experience would prove invaluable when COVID-19 emerged a decade later. The lessons learned from H1N1, including the importance of rapid vaccine development, early detection, and effective public health communication, would be applied during the COVID-19 pandemic, even as the scale and impact of the two viruses were vastly different.

COVID-19: A Global Crisis Like No Other

While HIV/AIDS was a slow-burning epidemic that spanned decades, COVID-19 exploded onto the global stage in December 2019 and spread to nearly every country in the world by 2020. Caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 became one of the most severe global health crises of the 21st century. Unlike HIV, which spread slowly and required long-term care, COVID-19’s rapid transmission and high fatality rate led to widespread panic and unprecedented efforts to curb its spread.

In the early months of the pandemic, health authorities struggled to understand the nature of the virus. It was clear that COVID-19 spread primarily through respiratory droplets, but its true range of symptoms was not initially well understood. While many people experienced mild to moderate symptoms—such as fever, cough, and fatigue—others suffered from severe respiratory distress, leading to hospitalization and, in some cases, death. The virus’s ability to cause both mild and severe illness in the same population made it particularly difficult to predict and contain.

As the virus spread rapidly across the globe, governments implemented a range of measures to slow its transmission. Lockdowns, social distancing, mask mandates, and travel restrictions were enforced in an attempt to “flatten the curve.” These measures, while necessary to reduce the strain on healthcare systems, led to significant economic and social disruption. Entire industries came to a halt, schools were closed, and millions of people lost their jobs. The pandemic forced societies to reevaluate everything from work and education to social relationships and global supply chains.

The rapid development of vaccines against COVID-19 was a breakthrough that marked a new chapter in the history of medicine. By late 2020, the first mRNA vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) were authorized for emergency use, followed by other vaccines using different technologies. The ability to produce effective vaccines in record time is a testament to the advances in biotechnology, global collaboration, and scientific innovation. However, widespread vaccine distribution remained a significant challenge, particularly in low-income countries, and the virus continued to evolve, leading to the emergence of new variants, such as Delta and Omicron, each with its own set of challenges.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect the world, even as vaccines, treatments, and new public health strategies have begun to mitigate its impact. The long-term consequences of the pandemic—both in terms of physical health, mental health, and economic stability—will continue to be felt for years to come. Yet, the virus has also driven innovation in healthcare, from telemedicine to vaccine research, and has fundamentally changed the way we live, work, and interact with one another.

The Invisible Hand of Viral Evolution: The Constant Threat

What links HIV, H1N1, COVID-19, and other impactful viruses in modern history is their ability to evolve and adapt in ways that are difficult for human societies to predict and control. The ongoing mutation of viruses—whether through the genetic recombination seen in the H1N1 pandemic or the evolution of variants in COVID-19—illustrates how viral evolution is an ongoing challenge for public health.

Viruses are inherently unstable; they evolve rapidly due to their high mutation rates. This makes them extraordinarily difficult to control. For example, HIV has proven remarkably adept at evading the immune system, constantly mutating to avoid detection and treatment. This is why researchers have struggled for decades to develop an effective HIV vaccine, and why the fight against the virus remains one of the most difficult in medical history.

COVID-19 has followed a similar path. Although vaccines have been effective in reducing severe disease and death, the virus continues to evolve. Variants such as Delta and Omicron have displayed increased transmissibility and some degree of immune escape, leading to renewed outbreaks and concerns about vaccine effectiveness. The need for booster shots and the potential for future variants underscore the ongoing nature of the battle against the virus.

In both HIV and COVID-19, the concept of viral evolution has reshaped how we approach vaccine development, treatment strategies, and public health measures. Scientists now recognize that a more dynamic, flexible approach to combating viruses—one that accounts for the possibility of new variants and mutations—is necessary to stay ahead of the curve. The ability to respond quickly to viral evolution will be a defining feature of future pandemics.

The Social and Economic Impact: From Stigma to Solidarity

While the direct health effects of viruses like HIV and COVID-19 are often the focus of public discourse, their social and economic impacts are equally profound. HIV/AIDS, for example, caused widespread fear and stigma, especially in the early years of the epidemic. The virus was associated with marginalized groups, including LGBTQ+ communities and people who used intravenous drugs, leading to discrimination and social isolation. This stigma not only affected people living with HIV but also slowed efforts to promote testing, treatment, and prevention. The fear of HIV led to panic, misinformation, and in some cases, even violence against those perceived to be at risk.

COVID-19, on the other hand, has shown how a virus can disrupt every aspect of modern society. The global economy was severely affected by lockdowns and travel restrictions, while mental health challenges escalated due to isolation, uncertainty, and loss. The pandemic exposed deep inequalities in healthcare access, with marginalized communities suffering disproportionately from both the virus and the economic fallout. In addition, the virus strained public health systems worldwide, especially in countries with limited resources.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has also led to a renewed sense of global solidarity. Efforts to develop and distribute vaccines, share scientific knowledge, and provide humanitarian aid have underscored the importance of cooperation in times of crisis. While the pandemic has highlighted the disparities and challenges in the global health system, it has also shown the potential for positive change when nations and organizations work together.

Conclusion: The Viruses That Changed History

From HIV to COVID-19, the most impactful viruses in modern history have reshaped the world in ways both predictable and unforeseen. HIV/AIDS forever changed our understanding of the virus-host relationship, pushing the boundaries of medical research and treatment. The H1N1 pandemic demonstrated the importance of swift, coordinated global responses to emerging viral threats. And the ongoing battle with COVID-19 is redefining our relationship with science, health, and one another.

The history of these viruses is a story of suffering, resilience, and innovation. As we continue to face viral threats, we can take solace in the knowledge that science, public health initiatives, and human solidarity will continue to evolve to meet the challenges of the future. The world is more connected, informed, and prepared than ever before, but the fight against viruses is far from over.