Mars has always fascinated humanity—a world of crimson deserts, colossal canyons, and ghostly traces of rivers long gone. For decades, scientists have searched for the fingerprints of water on its surface, knowing that where there is water, there might once have been life. Traditionally, that search led to the poles, where ice caps gleam beneath the thin Martian sunlight. Yet, recent discoveries hint that Mars may be hiding something unexpected—ice buried not at its frozen ends, but near its fiery heart.

In a study published in Nature Communications, researchers have proposed a startling idea: explosive volcanic eruptions on early Mars may have transported vast amounts of water ice to the planet’s equatorial regions. These ice deposits, if still preserved beneath the surface, could redefine our understanding of Mars’s climate, its geological evolution, and its potential for future human exploration.

When Fire Met Ice: A Planet in Turmoil

Billions of years ago, Mars was a very different world. Its surface was young and restless, its atmosphere thicker, and its volcanoes among the most powerful in the solar system. The planet’s towering peaks—such as Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system—stand as frozen monuments to this fiery past. Between 4.1 and 3 billion years ago, explosive eruptions rocked Mars’s surface, belching gas, ash, and steam into the sky.

According to planetary scientist Saira Hamid and her team, these eruptions may have played an astonishing double role: not only shaping the planet through fire, but also through ice. When volcanic eruptions released water vapor high into Mars’s cold, thin atmosphere, that vapor could have rapidly frozen, turning into ice crystals that fell as precipitation.

Their model suggests that, in just a few days, this process could have blanketed the surface with up to five meters of ice—enough to form a significant frozen layer that might survive for eons if protected beneath dust or volcanic debris. What began as an eruption of molten rock could have ended as a quiet snowfall across the red planet’s equatorial plains.

The Puzzle of Hidden Hydrogen

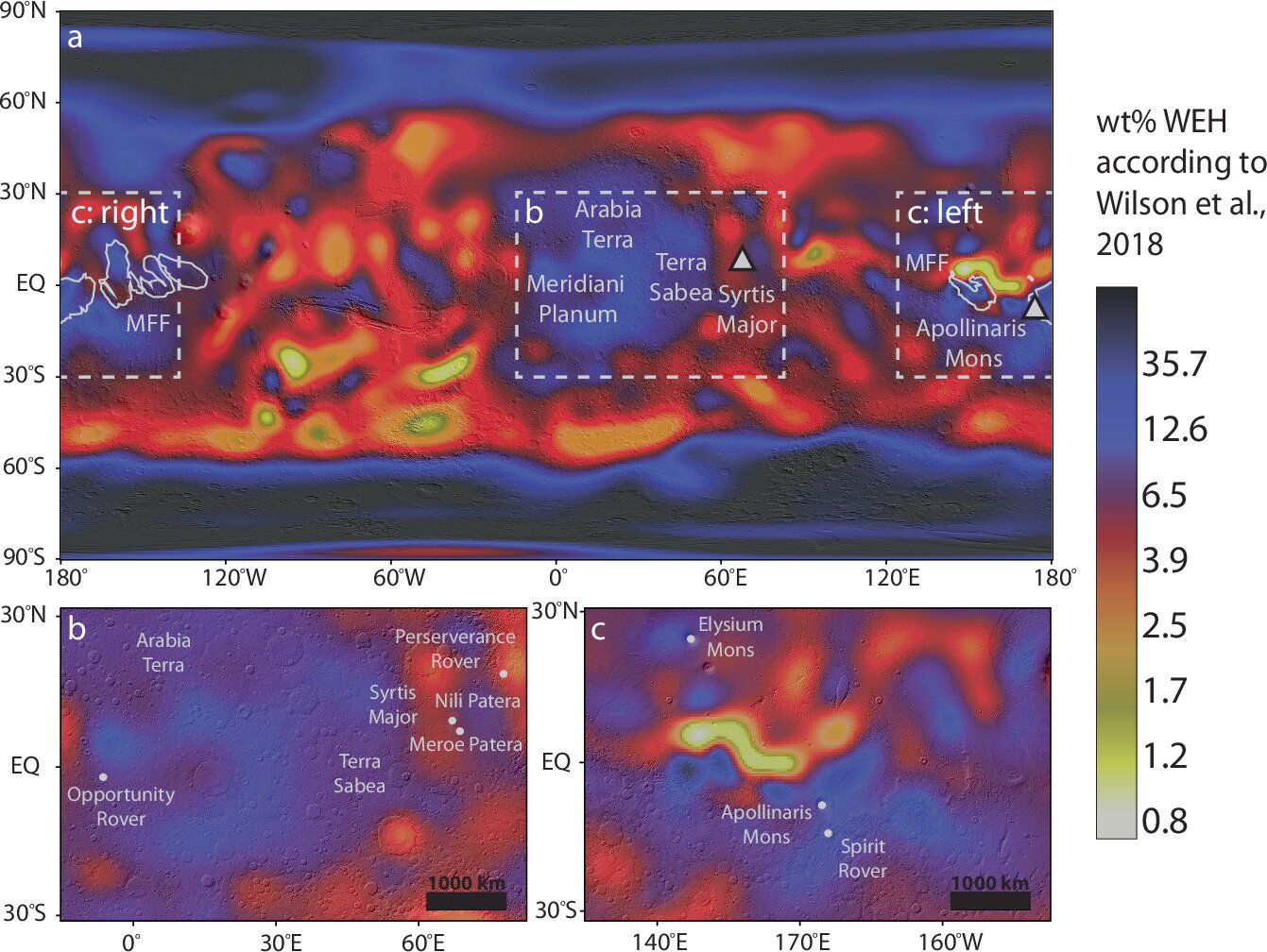

The idea of equatorial ice has puzzled scientists for years. Mars’s polar regions, with their perpetual cold, are natural repositories for frozen water, but the equator—where sunlight beats down most directly—seems too warm for long-term ice storage. Yet, spacecraft orbiting Mars have detected elevated levels of hydrogen in these very regions, a chemical clue that often points to the presence of water or ice below the surface.

If Hamid’s volcanic ice hypothesis holds true, it could explain this mystery. The hydrogen signals might not come from hydrated minerals or transient frost, but from ancient ice sheets trapped beneath layers of dust—remnants of a time when Mars’s atmosphere and climate were dramatically reshaped by fire and ash.

A Planet Caught in Its Own Winter

The study also offers another fascinating insight: volcanic eruptions may not have merely deposited ice—they could have helped preserve it. The same eruptions that released water vapor also spewed sulfuric acid and other gases into the Martian atmosphere. These gases would have reflected sunlight and triggered a planet-wide cooling effect, a kind of volcanic winter.

Such cooling could have lasted long after the eruptions themselves ended, allowing ice to accumulate and remain stable for extended periods. In a world already colder than Earth, this chilling effect may have turned Mars into an icy desert, freezing water deposits before they had a chance to sublimate into the thin air.

Ice as a Time Capsule

If this buried equatorial ice truly exists, it would be more than a geological curiosity—it would be a time capsule. Within its layers could lie traces of Mars’s ancient atmosphere, snapshots of volcanic activity, and perhaps even the chemical ingredients that once supported microbial life. Studying these deposits could unlock secrets not just about Mars, but about the processes that shape rocky planets throughout the solar system.

For planetary scientists, the possibility is thrilling. “If these equatorial ice deposits still exist,” the study suggests, “they could represent one of the most accessible reservoirs of water on Mars.” Water, of course, is essential—not only for understanding planetary history but also for sustaining future human explorers.

A Future Resource for Human Exploration

For astronauts who may one day set foot on Mars, water is everything. It means hydration, oxygen, and fuel—since water can be split into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket propulsion. The polar ice caps, while vast, are distant from many potential landing sites near the equator, where sunlight and mild temperatures make exploration more feasible.

If accessible ice lies beneath the equatorial surface, it could transform mission planning. Instead of hauling heavy water supplies from Earth, future explorers might simply dig beneath the Martian soil to find what they need. The implications stretch far beyond convenience—they touch on sustainability, independence, and the long-term dream of human settlement on another world.

The Story of a Living Planet

What makes this discovery so captivating is how it reframes Mars—not as a dead, unchanging sphere, but as a planet that once lived and breathed through cycles of fire and frost. It paints a picture of a world that has been both scorched by volcanic fury and sculpted by frozen water.

The red planet, often imagined as barren and static, emerges instead as a dynamic system where even destruction could create the seeds of preservation. Volcanic plumes that once darkened its skies may have given birth to hidden glaciers beneath its sands. Fire, paradoxically, may have made way for ice.

Peering Beneath the Surface

Proving this theory will not be easy. While satellites can detect hints of hydrogen, confirming the presence of buried ice requires direct investigation. Future missions—equipped with ground-penetrating radar, drills, or rovers—could probe beneath the Martian surface to search for these ancient deposits. NASA’s ExoMars and future missions by SpaceX or international space agencies might one day reveal the truth.

If confirmed, the discovery would revolutionize our understanding of Martian geology and climate history. It would suggest that Mars’s equator, once thought too arid for ice, may hold remnants of a volatile past where the elements clashed and intertwined.

Lessons for Earth and Beyond

There’s also a deeper lesson in this story—one that resonates beyond Mars. On Earth, too, volcanoes have shaped climates, altered ecosystems, and influenced the course of life. The parallels remind us that planets, no matter how distant, share the same fundamental forces: heat, water, atmosphere, and change.

By studying Mars, we also glimpse our own planet’s ancient struggles—the fires that forged continents, the ice ages that reshaped them, the delicate balance that allows life to flourish between extremes. Mars stands as both mirror and mystery, a reminder of how fragile and powerful planetary systems can be.

The Promise Beneath the Red Horizon

As humanity looks toward the future, Mars remains our most alluring destination. Every discovery deepens its intrigue: ancient riverbeds, whispering winds, and now the tantalizing possibility of equatorial ice born from volcanic fire.

Somewhere beneath its rust-colored dust, hidden from the sun and untouched for billions of years, there may lie the frozen echoes of Mars’s tumultuous youth. If explorers one day uncover these icy veins, they won’t just find water—they’ll find the story of a planet that once burned with life’s potential.

In that discovery, we may also find something of ourselves: a reflection of Earth’s restless spirit and the eternal human desire to seek, to understand, and to survive—no matter how far from home.

More information: Saira S. Hamid et al, Precipitation induced by explosive volcanism on Mars and its implications for unexpected equatorial ice, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63518-8