The idea of amplifying human strength has haunted the human imagination for centuries. Myths speak of heroes endowed with supernatural power, able to lift mountains or battle giants. In modern times, that ancient dream is no longer confined to legend. Exoskeletons—wearable machines that enhance human movement and strength—have begun to transform fantasy into engineering reality. These devices do not replace the human body; they embrace it, wrapping around muscles and bones to support, augment, and sometimes restore physical capability. In doing so, exoskeletons are quietly redefining what the human body can do.

At their core, exoskeletons represent a profound convergence of biology and technology. They sit at the intersection of physics, engineering, neuroscience, and medicine, translating mechanical force into human motion with increasing elegance. The emotional power of this technology lies not only in its promise of superhuman strength, but in its potential to return movement to those who have lost it, to protect workers from injury, and to reshape the limits of human endurance.

From Insects to Iron Suits: The Origins of the Exoskeleton Idea

The word “exoskeleton” originally comes from biology. Insects and crustaceans possess external skeletons that provide protection, structure, and leverage for movement. These natural exoskeletons are masterpieces of evolutionary engineering, combining strength with lightness and efficiency. When engineers borrowed the term, they also borrowed the underlying inspiration: an external structure that supports and enhances motion.

Early visions of mechanical exoskeletons emerged in the twentieth century, often driven by military imagination and industrial ambition. Engineers wondered whether machines could bear heavy loads while remaining responsive to human intent. The challenge was immense. Unlike a crane or a vehicle, an exoskeleton must move in harmony with a living body, responding instantly and safely to subtle shifts in balance and force.

Initial attempts were bulky and impractical, limited by weak actuators, slow computers, and insufficient power sources. Yet even these early prototypes revealed something important: human strength is not only a matter of muscle power but of coordination, leverage, and energy transfer. By improving how force is applied, machines could multiply what a human body is capable of achieving.

The Physics of Strength Augmentation

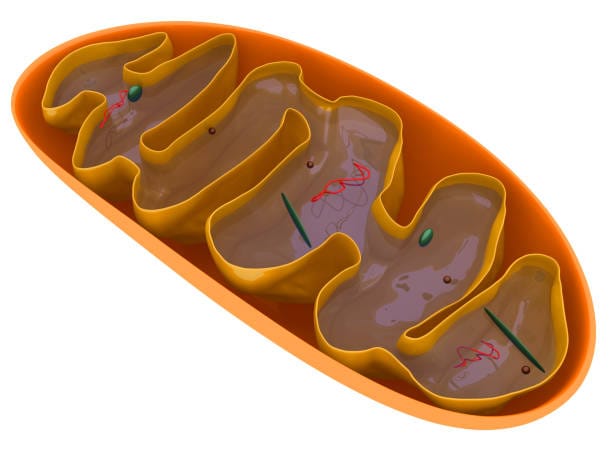

To understand how exoskeletons turn humans into “super-hulks,” it is essential to understand the physics behind human movement. When a person lifts an object, muscles generate forces that act on bones, which function as levers. The effectiveness of this system depends on muscle strength, joint geometry, and balance. Fatigue sets in because muscles consume energy and generate heat, and because joints experience stress.

Exoskeletons intervene directly in this mechanical process. They add external actuators—such as electric motors, hydraulic pistons, or elastic elements—that generate additional force at the joints. By aligning these actuators with human limbs, an exoskeleton can share the load, reducing the force required from the user’s muscles. In some designs, the machine provides most of the lifting force, while the human provides guidance and control.

Crucially, the laws of physics still apply. Energy must come from somewhere, typically from batteries or compressed fluids. Forces must be transmitted safely through rigid frames and soft interfaces. Stability must be maintained to prevent falls or injuries. The success of an exoskeleton depends on precise control of force, timing, and alignment—an intricate dance between machine and human body.

Types of Exoskeletons and Their Purposes

Modern exoskeletons can be broadly understood by their intended function, although the boundaries between categories are increasingly blurred. Some are designed for strength augmentation, allowing users to lift heavy objects with minimal effort. Others focus on endurance, reducing fatigue during repetitive tasks. Still others are medical devices, intended to assist rehabilitation or restore mobility.

Industrial exoskeletons are among the most widely deployed today. These systems are often passive or semi-active, using springs, dampers, or simple motors to support the back, shoulders, or legs. Their goal is not to create superhuman strength, but to reduce strain and prevent injury. By redistributing loads and supporting posture, they help workers perform physically demanding tasks more safely.

Medical exoskeletons are perhaps the most emotionally compelling. For individuals with spinal cord injuries, stroke, or neuromuscular disorders, these devices can enable standing, walking, and even climbing stairs. In these cases, the exoskeleton becomes an extension of the nervous system, translating user intent—sometimes detected through subtle muscle signals or neural interfaces—into coordinated movement.

Military and research exoskeletons push the boundaries of performance. These systems aim to allow soldiers or rescue workers to carry heavy equipment over long distances, traverse rough terrain, and operate with reduced fatigue. While such devices remain largely experimental, they illustrate the upper limits of what exoskeleton technology might achieve.

Human–Machine Symbiosis

One of the most fascinating aspects of exoskeletons is the way they blur the line between human and machine. Unlike tools that are held or operated at a distance, an exoskeleton is worn. It moves when the user moves, stops when the user stops, and must respond intuitively to intention. This requires sophisticated sensing and control systems capable of interpreting human motion in real time.

Sensors embedded in the exoskeleton measure joint angles, forces, and sometimes muscle activity. Control algorithms process this data to predict what the user intends to do next. The machine then provides assistance that feels natural rather than intrusive. When this interaction is successful, users often report a sense of transparency, as if the exoskeleton has become part of their body.

From a scientific perspective, this symbiosis raises deep questions about embodiment and agency. Where does the human end and the machine begin? As exoskeletons become lighter, smarter, and more responsive, they challenge traditional notions of physical ability and personal identity. Strength is no longer solely a property of muscle tissue; it becomes a shared attribute of human and technology.

Powering the Super-Human Dream

Energy supply remains one of the greatest challenges in exoskeleton development. Providing significant mechanical assistance requires power, yet the device must remain lightweight and wearable. Batteries are the most common solution, particularly lithium-based systems with high energy density. However, even the best batteries impose limits on operating time and performance.

Some exoskeletons use passive elements, such as springs or elastic bands, to store and release energy during movement. These systems do not require external power and can significantly reduce metabolic cost during repetitive tasks like walking or lifting. While they cannot provide unlimited strength, they demonstrate that clever mechanical design can achieve impressive results without heavy energy demands.

Research continues into alternative power sources, including fuel cells and energy harvesting systems that capture energy from the user’s own movement. Each approach involves trade-offs between weight, complexity, safety, and endurance. The physics of energy conservation ensures that there are no shortcuts, but innovation continues to push practical limits.

Exoskeletons in Medicine and Rehabilitation

Perhaps the most transformative impact of exoskeletons lies in medicine. For patients recovering from injury or living with paralysis, the ability to stand and walk can have profound physical and psychological benefits. Exoskeleton-assisted rehabilitation allows patients to practice natural movement patterns, which can stimulate neural plasticity and improve recovery outcomes.

These medical devices are carefully designed to prioritize safety and adaptability. They often include adjustable support levels, allowing therapists to gradually reduce assistance as patients regain strength and control. Advanced models integrate feedback systems that monitor gait symmetry, joint loading, and muscle activation, providing valuable data for personalized treatment.

Beyond physical benefits, the emotional impact of medical exoskeletons is immense. Standing upright after years in a wheelchair can restore a sense of dignity and autonomy. Walking, even with assistance, reconnects individuals with a fundamental human experience. In this context, exoskeletons are not about becoming superhuman, but about reclaiming what injury or illness has taken away.

Industrial Strength and Worker Safety

In factories, warehouses, and construction sites, physical labor remains essential despite increasing automation. Workers routinely lift heavy loads, maintain awkward postures, and perform repetitive motions that can lead to chronic injuries. Industrial exoskeletons address this problem by acting as wearable support systems that reduce biomechanical stress.

Unlike the dramatic powered suits of science fiction, most industrial exoskeletons are relatively simple. They may support the lower back during lifting or assist the shoulders during overhead work. By reducing the forces transmitted through joints and muscles, these devices can lower injury risk and extend working careers.

Scientific studies of industrial exoskeletons focus on biomechanics and ergonomics. Researchers measure muscle activity, joint loads, and fatigue to assess effectiveness. Results suggest that, when properly designed and used, exoskeletons can significantly reduce physical strain. However, they also highlight the importance of careful implementation, as poorly fitted or improperly used devices can introduce new risks.

Military Ambitions and Ethical Questions

The military interest in exoskeletons is driven by clear objectives: increase load-carrying capacity, enhance endurance, and reduce injury among soldiers. A soldier equipped with an effective exoskeleton could carry heavier equipment for longer distances, potentially changing the dynamics of combat and logistics.

Yet these ambitions raise ethical and strategic questions. Augmenting human strength for warfare forces society to confront the implications of technologically enhanced soldiers. Issues of responsibility, escalation, and long-term health effects must be considered alongside technical feasibility.

From a scientific standpoint, military exoskeletons face extreme challenges. They must operate reliably in harsh environments, function for long durations without recharging, and integrate seamlessly with other equipment. While progress continues, these constraints ensure that fully realized combat exoskeletons remain a work in progress rather than an imminent reality.

Control Systems and the Brain–Body Connection

The effectiveness of an exoskeleton depends not only on mechanical strength but on control. The device must interpret human intent accurately and respond without delay. This has led to intensive research into human–machine interfaces, including muscle-based and neural control methods.

Surface electromyography, which measures electrical signals produced by muscles, is commonly used to detect user intent. By analyzing these signals, control systems can predict movements before they fully occur, enabling smoother assistance. More advanced approaches explore direct neural interfaces, although these remain largely experimental.

These developments deepen the connection between physics, biology, and neuroscience. They reveal how electrical signals, mechanical forces, and cognitive intent converge to produce movement. In doing so, exoskeleton research contributes not only to engineering but to fundamental understanding of the human motor system.

Psychological and Social Dimensions

Becoming stronger through technology has psychological consequences that extend beyond physical performance. Users of exoskeletons often describe shifts in self-perception, confidence, and social interaction. Feeling capable of lifting heavy objects or walking independently can reshape identity and emotional well-being.

At the same time, there can be social challenges. Wearing an exoskeleton can attract attention, raise questions, or create feelings of difference. Acceptance depends on design, cultural context, and how the technology is presented. Devices that are discreet and comfortable are more likely to be embraced as normal tools rather than intrusive machines.

Understanding these human factors is essential for successful adoption. Exoskeletons are not just mechanical systems; they are social technologies that interact with values, expectations, and emotions.

The Limits of Super-Human Strength

Despite dramatic headlines, exoskeletons do not violate the laws of physics. They cannot provide infinite strength or eliminate fatigue entirely. Every gain in force or endurance comes with costs in energy, weight, and complexity. Moreover, the human body itself imposes limits. Bones, joints, and connective tissues can only tolerate certain loads, regardless of muscle assistance.

Scientific research therefore emphasizes balance rather than brute force. The goal is to enhance human capability while preserving safety and comfort. This approach reflects a broader lesson of physics: progress often comes not from extremes, but from optimization within constraints.

Exoskeletons and the Future of Human Capability

As technology advances, exoskeletons are likely to become lighter, smarter, and more integrated into daily life. Improvements in materials science, such as high-strength composites and soft robotics, promise devices that conform more naturally to the body. Advances in artificial intelligence will enable more intuitive control and adaptation to individual users.

The long-term implications are profound. Exoskeletons could reshape labor, healthcare, and even concepts of disability and aging. An older individual supported by an exoskeleton might maintain mobility and independence far longer than is currently possible. Workers could perform demanding tasks with reduced risk, and patients could recover function more effectively.

Yet these possibilities also demand careful ethical reflection. Access, affordability, and equitable distribution will shape who benefits from this technology. Physics and engineering can build powerful tools, but society must decide how they are used.

Conclusion: Strength Redefined

Exoskeletons are not merely machines that make people stronger. They represent a redefinition of strength itself, shifting it from a purely biological trait to a shared property of human and technology. Rooted in the principles of physics and refined through engineering, exoskeletons demonstrate how deeply understanding nature can lead to transformative innovation.

The image of the “super-hulk” captures imagination, but the true power of exoskeletons lies in their subtlety. They protect, restore, and extend human capability without erasing the human element. In doing so, they remind us that the future of strength is not about replacing the body, but about working with it—amplifying what it can already do while respecting the laws that govern both flesh and machine.