From the moment humankind first closed its eyes and slipped into the shifting landscapes of sleep, dreams have haunted and fascinated us. In the hush of night, images rise unbidden: loved ones long gone, gods who speak in riddles, beasts both feared and revered, journeys across impossible terrains. To the ancients, dreams were never meaningless. They were messages, visions, omens, and revelations—a secret language whispered by the cosmos to the soul.

For countless cultures, dreams stood at the intersection of the earthly and the divine, the human and the supernatural. They were a space where mortality and eternity touched, where gods, ancestors, and spirits stepped into the fragile human mind to deliver truths hidden from waking eyes. While today science explains dreams as products of neural firing and subconscious thought, our ancestors saw them as portals—bridges between realms.

To walk through ancient interpretations of dreams is to wander into the collective imagination of humanity itself. It is a journey into fear, faith, and wonder.

The Dream Temples of Ancient Egypt

In the heart of the ancient Egyptian world, dreams were inseparable from the sacred. Egyptians believed the night was a realm where the soul traveled beyond the body, brushing against gods and otherworldly forces. To them, dreams were not idle illusions but divine communications.

The Egyptians built “dream temples,” sanctuaries where the faithful sought prophetic visions through ritual sleep. Here, beneath the gaze of gods like Thoth, the deity of wisdom, and Serapis, a healing god, people engaged in “incubation”—a sacred practice of sleeping within temple walls to receive divine guidance. The dreamer might wake believing they had received instructions for healing, warnings about the future, or blessings from the gods.

Dream books written on papyrus offered interpretations: a dream of drinking warm beer might signal distress, while visions of the Nile rising could herald abundance. These dream manuals reveal how deeply the Egyptians intertwined spirituality and the subconscious. To them, the dream was not just an echo of the day—it was an encrypted message from eternity.

Mesopotamia: The Land Where Dreams Were Divine Scripts

In Mesopotamia, one of the cradles of civilization, dreams held tremendous weight. The Sumerians and Babylonians believed dreams were direct channels through which gods communicated with mortals. Epic literature like The Epic of Gilgamesh contains vivid dream sequences, often laden with symbolic warnings or promises.

Kings, especially, sought to decipher their dreams as clues to war, prosperity, or divine favor. Priests and specialized interpreters called baru were tasked with unraveling these nighttime visions. Their methods combined symbolism with ritual, reflecting the belief that dreams carried cosmic significance.

The Babylonians even divided dreams into “sent by gods” and “sent by demons.” Good dreams were blessings, but nightmares were feared as intrusions from malevolent spirits. This duality mirrored their worldview: the cosmos was a battlefield of divine and demonic forces, and dreams were where this battle often touched human lives.

Greece: Dreams Between Gods and Philosophy

If Egypt and Mesopotamia saw dreams as divine edicts, ancient Greece wove them into both myth and philosophy. To the Greeks, dreams could be divine messages, psychological expressions, or even a glimpse of the soul’s journey.

Temples dedicated to Asclepius, the god of healing, became famous for dream incubation. The sick slept in these sanctuaries hoping for a dream in which Asclepius or his serpents appeared, prescribing remedies. Such visions were considered sacred medicine, merging spirituality with health.

Greek philosophers, meanwhile, offered diverse interpretations. Plato suggested that dreams expressed hidden desires, bubbling up when reason rested. Aristotle, more rationally, viewed dreams as echoes of bodily processes and impressions from daily life. To him, dreams were not divine revelations but natural phenomena of the mind.

Yet even as philosophers sought rational explanations, Greek myths brimmed with dream deities. Morpheus, the god of dreams, sculpted visions for mortals, while his brothers Phobetor and Phantasos conjured dreams of beasts and objects. Dreams were seen as art forms of the gods, crafted from imagination and shadow.

Rome: Practicality and Prophecy in the Night

The Romans inherited much of their dream lore from Greece but added their own pragmatic flair. To them, dreams were both prophecy and political tools. Roman generals often consulted dreams before battles, seeing them as divine endorsements or warnings.

Cicero, the great orator, debated whether dreams truly came from the gods or were simply products of the mind. Yet Roman society embraced dream interpretation as part of public life. Even emperors recorded and acted upon their dreams, sometimes changing policies or military campaigns because of them.

Dream manuals circulated widely, echoing Egyptian and Greek traditions. However, the Roman approach reflected their culture’s practical spirit: dreams were not only metaphysical—they were instruments for guiding daily decisions, from politics to marriage.

India: Dreams as Karma and Cosmic Signals

In ancient India, dreams were seen through the spiritual lens of karma, dharma, and cosmic cycles. Hindu scriptures like the Upanishads and Mahabharata describe dreams as layered realities, ranging from illusions caused by the restless mind to true glimpses of the soul’s journey.

Some dreams were considered reflections of past-life deeds, karmic residues surfacing in sleep. Others were prophetic, revealing future events. The Atharva Veda, one of the oldest sacred texts, even categorizes dreams—some as auspicious, others as ominous.

Buddhist teachings also engaged with dreams, often cautioning against attaching too much importance to them, since dreams, like life itself, were impermanent illusions. Yet many Buddhist stories recount monks receiving guidance or inspiration through dreams, suggesting that, while fleeting, dreams could still serve as spiritual signposts.

In India, dreams were more than personal—they were cosmic dialogues. To dream was to touch the eternal flow of karma, the cycles of rebirth, and the universal law of cause and effect.

China: Dreams as Balance and Journey

In ancient China, dreams were seen through the lens of balance, harmony, and spirit travel. Taoist philosophy suggested that dreams were journeys of the soul, temporarily freed from the body. In this view, the dreamer’s spirit wandered other realms, meeting ancestors, gods, or spirits.

The Zhou Li (Rites of Zhou) and other classical texts describe dream interpretation as part of divination practices. Dreams were believed to reveal disturbances in the balance of yin and yang, or to signal harmony restored. A dream of flowing water might symbolize life’s continuity, while broken objects could warn of discord.

One of the most famous dream passages in Chinese philosophy comes from Zhuangzi, who once dreamed he was a butterfly. Upon waking, he questioned whether he was a man who dreamed he was a butterfly or a butterfly now dreaming he was a man. This paradox captured the Chinese view of dreams as a space where reality and illusion intertwined.

Indigenous Cultures: Dreams as Spirit Bridges

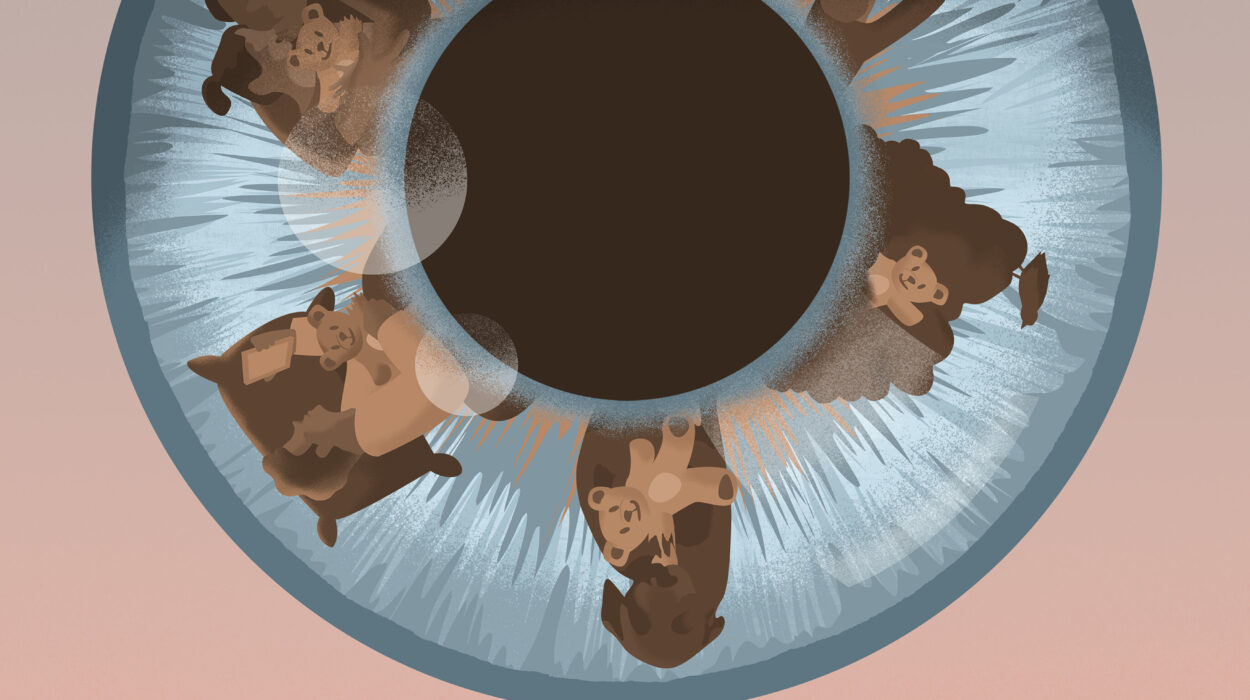

Beyond the great civilizations, indigenous cultures around the world developed rich dream traditions deeply entwined with spirituality. For many Native American tribes, dreams were sacred messages from the spirit world. The Ojibwe people crafted dreamcatchers to filter dreams, allowing good visions to reach the sleeper while trapping nightmares.

In Australia, Aboriginal peoples held the concept of the “Dreamtime,” a sacred cosmology where ancestral beings shaped the world. While Dreamtime is not the same as personal dreaming, it reflects how sleep visions were woven into their understanding of creation, law, and identity.

African traditions, too, often treated dreams as ancestral communications. To dream of an ancestor was not a random occurrence but a visitation carrying advice, blessing, or warning. Shamans and spiritual leaders interpreted these dreams, ensuring that communities lived in harmony with the unseen.

The Common Threads of Ancient Dreaming

Though separated by geography and culture, the ancients shared strikingly similar beliefs about dreams. Nearly everywhere, dreams were seen as:

- Messages from beyond—whether from gods, spirits, or ancestors.

- Prophecies of the future—signs of coming prosperity or disaster.

- Windows into the soul—revealing desires, fears, or karmic ties.

This universality suggests something profound: humanity has always sensed that the sleeping mind is not silent. The dream world, with its surreal imagery and emotional power, has always demanded meaning.

Modern Science and Ancient Wonder

Today, neuroscience explains dreams as patterns of brain activity, memory processing, and emotional regulation. REM sleep, where most vivid dreaming occurs, is now understood as crucial for learning and psychological balance. Freud suggested dreams were wish-fulfillments; Jung saw them as messages from the collective unconscious. Modern theories view them as simulations that prepare us for real-life challenges.

And yet, even with science’s advances, dreams retain their mystery. Who has not awoken from a vivid dream with the feeling that it meant something more? Who has not wondered if an ancestor, a god, or the universe itself was whispering in symbols?

The ancients may not have had neuroscience, but they had awe. They saw dreams not merely as random firing neurons but as sacred encounters with the unknown. In their myths and rituals, they gave voice to the wonder that still lives in us.

The Eternal Dreamer

Across Egypt’s temples, Mesopotamia’s ziggurats, Greece’s sanctuaries, India’s ashrams, China’s philosophies, and the campfires of indigenous peoples, dreams were bridges—connecting earth and sky, mortal and divine, self and cosmos. To dream was to journey, to receive, to awaken in another dimension.

Though modernity explains dreams with science, it cannot strip them of their poetry. We are still dreamers, still seekers, still interpreters of the night’s riddles. The ancients remind us that even in sleep, we are not alone. We walk with gods, with ancestors, with the timeless mysteries of existence.

And when we awaken, carrying fragments of visions half-forgotten, we carry also the legacy of countless generations who looked at their dreams and whispered: This means something.