Few ecological stories have captured the public imagination like the return of wolves to Yellowstone National Park. For nearly three decades, documentaries, news articles, and textbooks have repeated a dramatic narrative: wolves returned, elk declined, and vegetation instantly rebounded in one of the strongest trophic cascades ever recorded. But a new re-analysis suggests the truth is more nuanced — not a fairy tale, not a failure, but a more complex and conditional reality than the simplified success story implies.

In a detailed critique published in Global Ecology and Conservation, researchers from Utah State University and Colorado State University argue that a high-profile 2025 study by Ripple and colleagues exaggerated the ecological power of wolves by relying on methods that inflated plant recovery signals. Their conclusion does not deny that predators matter; it redefines how, when, and to what degree they reshape ecosystems.

A Claim Under the Microscope

The disputed paper asserted that the return of wolves triggered an exceptionally strong cascade: with elk pressured by predators, browsing decreased, and willow stands across the park reportedly grew in dramatic fashion — a 1,500 percent increase in crown volume. But according to the authors of the critique, that headline number was mathematically inevitable, not biologically meaningful.

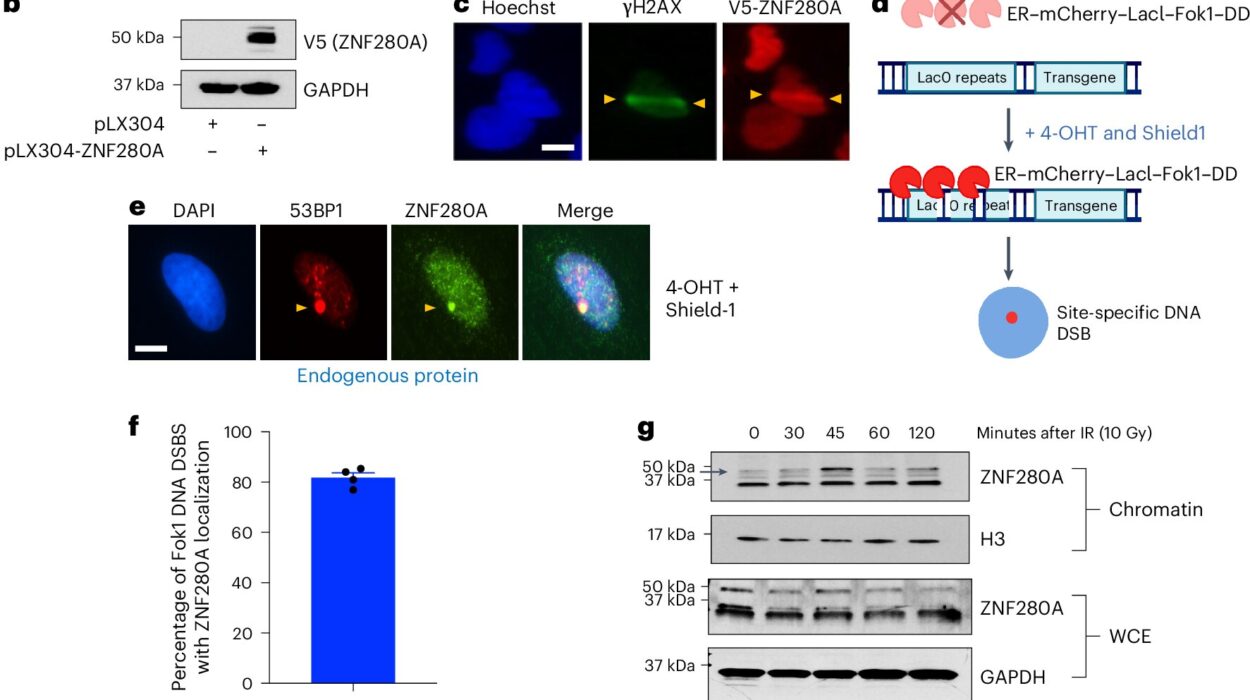

The volume estimate came from a model that used willow height both to define and to predict volume. That means the relationship looked strong by design, even if willow growth in nature had remained unchanged. If the same variable appears on both sides of the equation, the output cannot help but agree with itself. The problem is not technical hair-splitting; it undermines the central claim.

When Models Meet the Real World

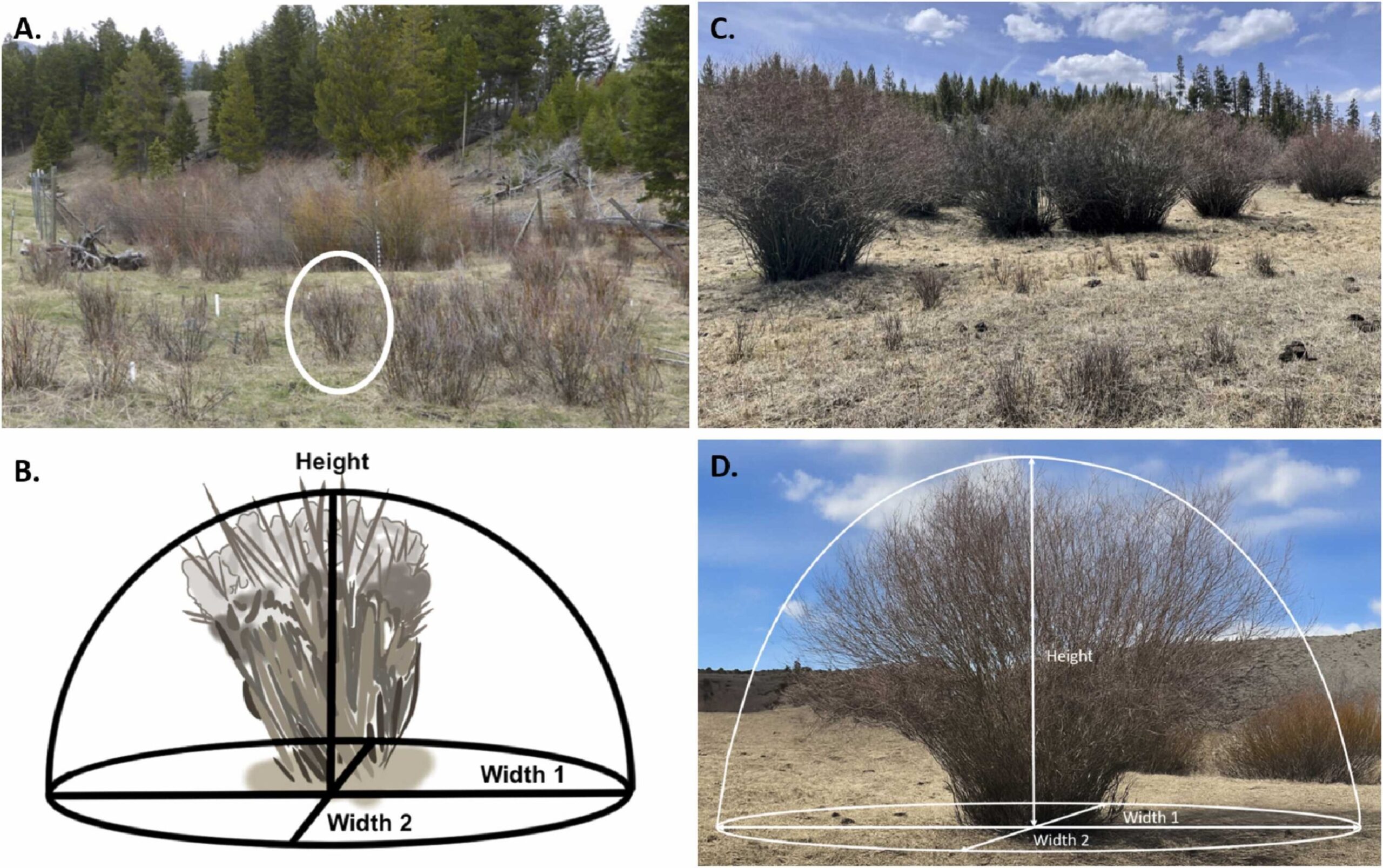

The critique identifies compounding issues beyond circular definition. Willows used in the analysis were often heavily browsed and misshapen — a condition that violates the very assumptions of the height-to-volume model used to measure growth. Because the model assumes a predictable plant shape that real willows did not have, it exaggerated growth trends.

The comparison of willows across time was also flawed. Most of the plots measured in 2020 were not the same physical locations measured in 2001. Any difference could therefore reflect sampling bias rather than true ecological change. Treating these mismatched samples as a before-and-after test created a false impression of systematic transformation.

Global comparisons added another layer of distortion. Ripple et al. framed Yellowstone as a top-tier trophic cascade compared to other ecosystems, yet such rankings assume stable equilibrium — a condition Yellowstone has not reached. The system is still recovering from 20th-century hunting, hydrologic alteration, climate variation, and changing human policies. Declaring it “one of the world’s strongest cascades” under non-equilibrium conditions misclassifies what the data can support.

The Danger of a Single Explanation

The critique further notes that selective photographs, omission of hydrological drivers, and failure to account for human hunting pressure simplified a multi-factor reality into a wolf-centric narrative. When such complexities are excluded, the resulting explanation feels cleaner and more cinematic — but becomes scientifically brittle.

After correcting for these issues, the researchers found no evidence for a large, system-wide willow recovery driven by wolf predation. Instead, the pattern suggests modest and patchy increases explained not by predators alone but by a blend of site conditions, moisture availability, browsing intensity, and local ecological feedbacks.

Wolves Still Matter — But Not in a Vacuum

The researchers are explicit that their critique is not a dismissal of predator importance. Wolves influence elk behavior, alter browsing pressure, and affect vegetation — but their effects are conditional, not universal. Strong claims of strong cascades require strong proof, not elegant stories.

This clarification helps reconcile two long-standing interpretations of the same dataset. Ripple et al. took the numbers as evidence of a powerful cascade; Hobbs et al., who gathered the field data over two decades, found much weaker effects. The new critique explains the discrepancy: one conclusion rests on methodological inflation, the other on experimental realism.

Why Accuracy Matters in an Age of Ecological Crisis

The Yellowstone wolf recovery remains a landmark conservation achievement. But conservation does not need embellished success stories to be meaningful. If science overstates evidence, it risks eroding trust when claims are later corrected. Ecology is inherently complex — influenced by time-lags, climate variation, human decisions, and spatial heterogeneity. Recognizing that complexity strengthens, rather than weakens, the case for cautious and evidence-based restoration.

In a world hungry for simple narratives, the revised lesson from Yellowstone is more intellectually demanding but more honest: predators can reshape landscapes, but they do so within constraints, contingencies, and contexts. Understanding those boundaries is not a step backward — it is the step that allows ecology to remain a science rather than a story.

More information: Daniel R. MacNulty et al, Flawed analysis invalidates claim of a strong Yellowstone trophic cascade after wolf reintroduction: A comment on Ripple et al. (2025), Global Ecology and Conservation (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.gecco.2025.e03899