Beneath the surface of our skin, hidden within the moist recesses of our bodies, and lingering silently in the air around us, thrives a mysterious and often overlooked kingdom—fungi. Most people associate fungi with mushrooms dotting the forest floor, mold on old bread, or perhaps the yeast that makes bread rise and beer ferment. But this ancient and diverse group of organisms is capable of much more than just culinary or ecological functions. Fungi can also be dangerous—silent invaders that exploit the vulnerabilities in our defenses, taking root in the most intimate parts of our biology.

Unlike bacteria and viruses, which often attract media attention with dramatic outbreaks and pandemics, fungal infections rarely make headlines. Yet they can be insidious, persistent, and in some cases, deadly. They exploit cracks in our skin, imbalances in our microbiome, and weaknesses in our immune system. From the common annoyance of athlete’s foot to the life-threatening complications of systemic Candida infections, fungi are a formidable and underappreciated threat to human health.

Ancient Organisms, Modern Threats

Fungi are among the oldest life forms on Earth. They predate humans by hundreds of millions of years and have co-evolved with us in complex and sometimes contradictory relationships. Some fungi help us digest food and keep harmful microbes at bay. Others ferment our favorite beverages and decompose organic waste, returning nutrients to the soil. But a select few have evolved into opportunistic pathogens—organisms that, under the right circumstances, can turn from harmless cohabitants into ruthless invaders.

These pathogens are not as straightforward as bacteria or viruses. They are eukaryotes, just like us, which means their cellular machinery is remarkably similar to our own. This biological resemblance is precisely what makes them so difficult to treat. Antifungal drugs must walk a tightrope: they must be powerful enough to kill the fungus but gentle enough not to harm the human host.

The Humble Itch: Athlete’s Foot and the Trichophyton Menace

It usually begins with a mild itch between the toes. Redness. Peeling. A burning sensation that makes walking uncomfortable. For many, this is the first and perhaps only encounter with a fungal infection: athlete’s foot, known medically as tinea pedis. It is so common, so mundane, that people often treat it with little more than a shrug and an over-the-counter cream. But behind this irritation lies a surprisingly resilient and adaptable fungus: Trichophyton.

Trichophyton rubrum and its cousins are dermatophytes—fungi that feast on keratin, the tough protein that forms the outer layer of human skin, hair, and nails. These fungi have evolved to thrive in warm, damp environments: locker rooms, communal showers, sweaty socks, and the inside of your favorite gym shoes. Once they gain a foothold, they spread outward in circular patterns, causing the characteristic ring-shaped rash.

Though rarely life-threatening, dermatophyte infections can be stubborn. They can spread to other parts of the body—jock itch, ringworm, and fungal nail infections are all cut from the same biological cloth. In immunocompromised individuals or the elderly, even these common infections can spiral into serious complications. And as antifungal resistance grows, even simple treatments may begin to fail.

Yeast: Friend, Foe, and Everything In Between

Not all fungi wear their threats on the outside. Some are more subtle, more internal—none more so than Candida, a genus of yeast that lives quietly in the gastrointestinal tract, mouth, and genital regions of most people. In healthy individuals, Candida is kept in check by a robust immune system and a diverse microbiome. But under stress—after a course of antibiotics, during illness, or in people with compromised immunity—Candida can seize the opportunity to multiply unchecked.

The result is candidiasis, a spectrum of infections ranging from annoying to fatal. The most familiar is oral thrush, where white, curd-like patches appear on the tongue and cheeks. Vaginal yeast infections are another common manifestation, causing itching, irritation, and a thick, white discharge. These conditions, while deeply uncomfortable, are typically treatable with antifungal medications.

But Candida has a darker side. In hospitals and intensive care units around the world, Candida albicans and its increasingly drug-resistant cousin Candida auris have emerged as serious threats. These fungi can enter the bloodstream through catheters, surgical wounds, or compromised mucosal barriers, causing systemic infections known as invasive candidiasis. Once inside, they can colonize the heart, brain, kidneys, and eyes, triggering septic shock and multi-organ failure. The mortality rate can reach 40%, even with aggressive treatment.

The Rise of Candida auris: A Global Wake-Up Call

In 2009, doctors in Japan isolated an unfamiliar yeast from a patient’s ear canal. At first, it seemed innocuous. But within a few years, Candida auris had appeared in hospitals around the world—in India, Venezuela, South Africa, the UK, and the United States. Unlike most fungi, which require specific environments to thrive, C. auris could survive on surfaces for weeks, resist most antifungal drugs, and spread from person to person in healthcare settings.

This was unprecedented. Fungal infections had rarely behaved like bacterial superbugs, yet C. auris acted like one—eluding cleaning agents, colonizing medical equipment, and striking patients already weakened by other illnesses. Worse still, its identification required sophisticated laboratory techniques, and it was often misidentified as other species, delaying effective treatment.

Epidemiologists now consider C. auris a top-tier public health threat, and its emergence has sparked renewed interest in fungal pathogenesis and infection control. But it has also exposed the fragility of our antifungal arsenal. Most antifungal drugs fall into just a few classes—azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes—and resistance to one can quickly lead to treatment failure. With few new drugs in development, the threat of untreatable fungal infections looms large.

When the Immune System Cracks: Aspergillus and the Breath of Mold

Not all fungi announce their arrival with rashes or mucosal discomfort. Some are breathed in quietly, every day, by everyone. Aspergillus is one such genus. Its spores are ubiquitous—present in soil, dust, and decaying vegetation. For healthy people, inhaling Aspergillus spores is harmless. But for those with weakened lungs, chronic illnesses, or compromised immune systems, these spores can become deadly seeds.

Invasive aspergillosis is a condition where Aspergillus grows inside the lungs and spreads to other organs. It primarily affects patients with leukemia, organ transplants, or AIDS. It often begins as a fever unresponsive to antibiotics, followed by respiratory distress and the spread of fungal masses throughout the body. Without prompt antifungal treatment, it is almost always fatal.

But Aspergillus can also affect people with asthma or cystic fibrosis, triggering allergic reactions and chronic lung damage. In rare cases, it forms a fungal ball—an aspergilloma—within pre-existing lung cavities, such as those left behind by tuberculosis. Surgery may be the only option.

In all its forms, Aspergillus reminds us that the air we breathe can carry hidden dangers—and that even the act of respiration can become a battleground between host and pathogen.

Cryptococcus and the Silent Invasion of the Brain

Among the most insidious fungal pathogens is Cryptococcus neoformans, a yeast found in soil and bird droppings. Like many opportunistic fungi, it poses little threat to healthy individuals. But in people with compromised immune systems, especially those with advanced HIV/AIDS, it can cause a devastating form of meningitis.

Cryptococcal meningitis often begins with subtle symptoms: headache, fever, fatigue. But it progresses quickly, leading to confusion, seizures, and coma. The fungus enters the brain by crossing the blood-brain barrier, a normally impervious shield. Once inside, it triggers inflammation, increased intracranial pressure, and neural damage. Without prompt diagnosis and treatment, mortality rates are high.

The global burden of cryptococcal meningitis is immense. In sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV is prevalent and access to antifungal medications is limited, hundreds of thousands die each year from this infection. Even in high-income countries, it remains a stubborn foe—requiring prolonged treatment with drugs that can be toxic and difficult to tolerate.

A Climate of Fungal Opportunity

In recent years, researchers have begun to explore a disturbing possibility: that climate change is making fungal infections more common, more severe, and more unpredictable. Warmer temperatures are forcing fungi to adapt to human body heat—previously a natural barrier to many species. Melting permafrost, shifting ecosystems, and increased human-wildlife contact all contribute to the emergence of new fungal threats.

In 2023, scientists reported the discovery of Candida tropicalis strains with enhanced thermal tolerance. Others have warned that the warming climate could accelerate the rise of thermally tolerant species that, like C. auris, might cross the species barrier and begin infecting humans.

At the same time, changes in land use, agriculture, and travel have brought humans into closer contact with previously isolated fungal reservoirs. Fungal pathogens that once only affected trees, plants, or animals may find new niches in human hosts. As our immune systems struggle to keep pace, the age of the fungal pandemic may no longer be the stuff of science fiction.

The Struggle to Treat: Antifungal Resistance and the Search for New Weapons

The fight against fungal infections is hampered by a stark reality: we have far fewer tools to combat fungi than we do for bacteria. Penicillin revolutionized the treatment of bacterial infections in the 20th century. But antifungal innovation has lagged behind. The main classes of antifungal drugs—azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes—are decades old, and fungi are increasingly developing resistance to all three.

Resistance arises through a variety of mechanisms: efflux pumps that eject drugs, mutations that alter drug targets, biofilm formation that shields fungi from harm. These defenses make treatment increasingly difficult, especially in hospital settings where fungi can evolve rapidly.

Pharmaceutical companies have historically been reluctant to invest in antifungal development due to high costs and limited markets. But with the rise of C. auris and other multidrug-resistant fungi, this attitude is slowly shifting. New drugs like ibrexafungerp and fosmanogepix show promise in early trials. But for now, doctors must rely on early diagnosis, aggressive treatment, and strict infection control to contain outbreaks.

Hope in the Microbiome

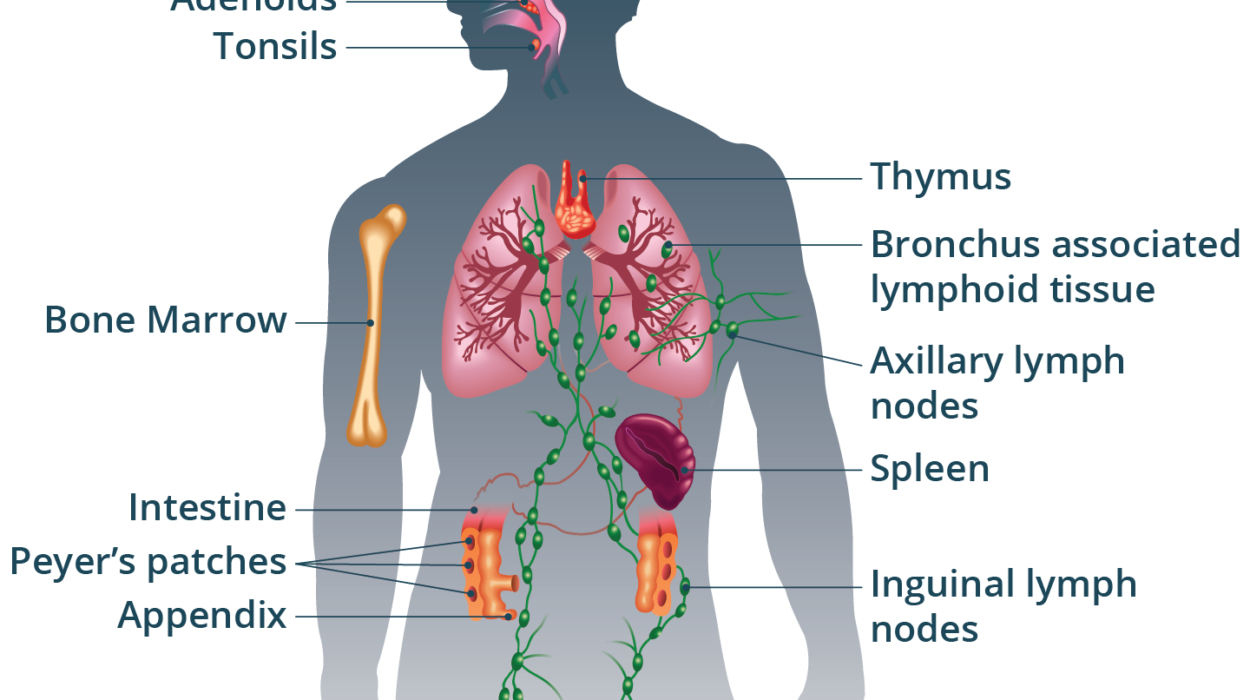

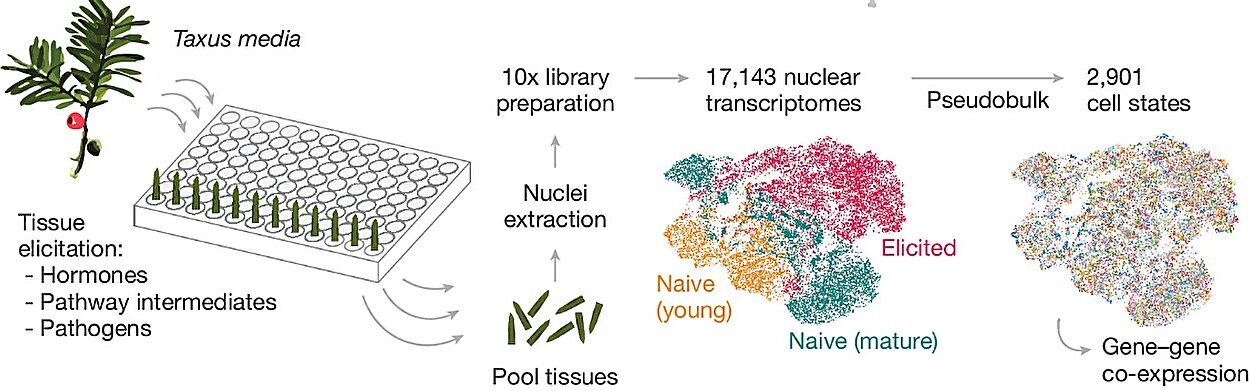

Amid these challenges, scientists are exploring new frontiers—especially the human microbiome, the vast community of microbes that lives on and within us. It is becoming clear that our bacterial allies play a critical role in keeping fungal invaders at bay. Disruption of this balance—by antibiotics, poor diet, or illness—creates a vacuum that fungi eagerly fill.

Probiotic therapies, fecal microbiota transplants, and microbiome-based diagnostics are emerging as potential tools to prevent and treat fungal infections. By restoring microbial harmony, we may be able to stop fungi before they take hold.

Researchers are also studying the immune system’s response to fungi in greater detail than ever before. New immunotherapies, vaccines, and antibody-based treatments could offer a future in which fungal infections are no longer an afterthought but a central focus of medical science.

A Final Reflection: Knowing the Enemy

Fungi are neither friend nor foe by nature. They are survivors—adaptable, ancient, and capable of both beauty and destruction. They live within us, around us, and above us in the air we breathe. For most of human history, we coexisted with them in relative peace. But that balance is shifting.

As medicine advances and more people live with chronic illness, organ transplants, or immune suppression, the door is opening wider to fungal invaders. As our climate warms and our ecosystems change, fungi are evolving to meet us in new ways.

Understanding fungi—how they live, spread, and harm—is not just a matter of curiosity. It is a matter of urgency. The next great medical challenge may not be viral or bacterial. It may come quietly, invisibly, riding on a breath of air or hidden in a hospital hallway. And when it comes, we must be ready—not with fear, but with knowledge, vigilance, and respect for the strange and shadowy kingdom that has always walked beside us.