Beneath the polished surface of adulthood, the brain often carries the invisible echoes of early pain. Now, a new neuroimaging study from China has provided deeper insight into how childhood trauma doesn’t just leave emotional scars—it subtly reshapes the architecture of the brain itself.

Published in the journal Neuroscience, the study offers compelling evidence that survivors of childhood trauma tend to have reduced cortical surface area and volume in specific brain regions. These alterations, researchers say, may act as biological imprints of early suffering—shadows etched into the brain’s landscape, long after the wounds of youth have faded from view.

The Unseen Wounds of Childhood

Childhood trauma is not always visible. It can hide behind quiet eyes, good grades, and adult success. But psychologists have long known that experiences like abuse, neglect, loss of a caregiver, and chronic instability in early years can fundamentally alter a person’s emotional and psychological development.

This new study, led by researcher Chengming Wang and colleagues, goes a step further—showing how such trauma might physically reshape the brain’s surface, potentially influencing everything from emotional regulation to cognitive function.

“Experiencing trauma during sensitive developmental windows appears to alter how the brain is wired and structured,” Wang said. “These changes may have long-term consequences for emotional health and behavior.”

Mapping Trauma in the Brain

To explore the brain’s response to early adversity, the research team scanned the brains of 215 healthy adults aged 18 to 44 using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). None of the participants had a diagnosed psychiatric or neurological disorder, and none were receiving psychiatric treatment or had a history of substance abuse.

Each participant also completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form, a widely used self-assessment tool for identifying early adverse experiences. Based on their responses, the researchers classified 57 participants as having experienced childhood trauma and 158 as not.

What they discovered in the brain scans was both striking and specific.

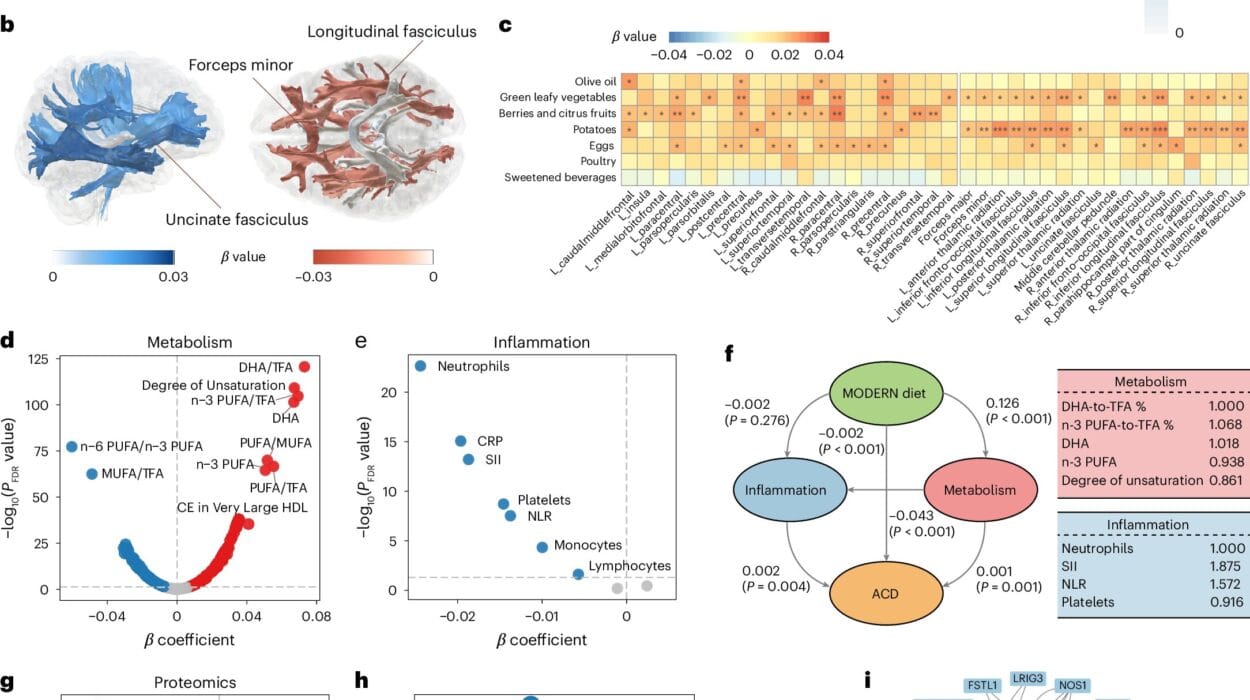

Participants with a history of childhood trauma had reduced surface area in a cluster of brain regions on the left side of the brain—namely, the precentral gyrus, postcentral gyrus, and paracentral lobule. Additionally, they had lower cortical volume in the postcentral gyrus.

These brain regions serve vital functions. The precentral gyrus is key for voluntary movement, acting as a control center for muscles. The postcentral gyrus handles sensory input—everything from the feel of a warm cup of tea to the pressure of someone’s hand on your shoulder. And the paracentral lobule integrates motor and sensory functions, particularly those connected to the lower limbs.

In other words, trauma doesn’t just affect how people feel or remember—it may shape how they experience the world physically.

Functional Ripples: When Brain Connections Change

But structure was only part of the story. Wang and his team also explored how these brain areas functionally connect to other regions.

Their analysis revealed that the regions with reduced cortical volume showed decreased connectivity to the bank of the superior temporal sulcus, the inferior parietal gyrus, and the supramarginal gyrus—areas involved in emotion, language processing, and empathy. Meanwhile, the regions with reduced surface area showed increased connectivity to the left postcentral gyrus, superior parietal gyrus, and supramarginal gyrus.

This contrast—some connections dampened, others amplified—suggests the brain may attempt to adapt or reroute its processing systems in response to early trauma. Yet these compensatory changes could also lead to emotional dysregulation, heightened sensitivity to stress, or dissociation.

“The childhood trauma group exhibits abnormalities in cortical structure and functional connectivity which are related to aberrant emotional and cognitive functions,” the study authors concluded. “These findings may serve as neuroimaging biomarkers of childhood trauma.”

Toward a Biological Fingerprint of Trauma?

In a world where emotional pain is often dismissed for lack of physical proof, this research pushes toward a new possibility: a measurable, biological fingerprint of psychological trauma.

Using the observed structural and functional differences, the team developed a statistical model to predict whether a person had experienced childhood trauma. The model correctly identified trauma survivors with 78% accuracy—a promising figure, though not definitive.

Still, the results raise tantalizing possibilities for the future of psychiatry and trauma therapy. Could brain imaging someday be used to detect the hidden wounds of childhood? Could it guide personalized treatments for trauma-related disorders? Could it help validate a patient’s suffering when words fall short?

Caution in Interpretation

While the findings are compelling, they come with caveats. The model’s 78% accuracy may sound impressive, but given that over 70% of participants were trauma-free, even a simple guess based on group size would have yielded a high success rate. In other words, while the model shows promise, it isn’t yet ready for clinical use.

Additionally, the brain is a remarkably resilient organ. It often reroutes functions when damage occurs—a concept known as functional redundancy. This means that while structural changes exist, the brain may still find alternate ways to function. That’s why different studies sometimes show inconsistent results when trying to pinpoint the neural “signature” of trauma.

A Window Into Healing

Despite its limitations, this research opens a new window into understanding the long arc of trauma. It shows that pain can be more than psychological—it can be physiological, structural, enduring. But it also suggests the brain’s story is one of both vulnerability and adaptation.

Knowing this, therapists and clinicians may be better equipped to treat trauma survivors with compassion, patience, and science-backed support. And for survivors themselves, studies like this one offer something even more powerful: validation.

If trauma rewires the brain, then healing is not simply a matter of “moving on.” It is a process of re-learning, re-connecting, and—perhaps—reclaiming the very architecture of the self.

Looking Ahead

The researchers at Chengdu and beyond hope this study inspires more in-depth investigation into the biological pathways of trauma—and eventually, the development of therapies that address the brain as both an emotional and physical entity.

In a society where childhood pain often lingers in silence, science is beginning to listen to the whispers written in neurons. And with each study, we move closer to understanding how early experiences shape us—and how, with insight and care, we might reshape the future for those who’ve lived through the darkest chapters too young.