Music is often described as the universal language, capable of moving us emotionally and uniting cultures across the world. But new research suggests it may also hold a deeper connection to the way our brains develop the ability to communicate. A groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications by researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery has revealed a striking link between musical rhythm skills and developmental speech-language disorders.

This discovery highlights a truth we are only beginning to understand: the rhythms we keep in music are closely tied to the rhythms we keep in speech, language, and even reading. The findings not only open doors to a richer understanding of how the brain processes communication but also point toward new ways to help children and adults struggling with speech and language difficulties.

Developmental Communication Disorders and Their Impact

Communication disorders are far more than a clinical label—they shape lives in profound ways. Conditions like developmental language disorder, dyslexia, and stuttering affect millions of people worldwide, often starting in childhood and carrying challenges into adulthood. These disorders can make it difficult to acquire language, interpret written words, or speak fluently.

The effects ripple outward: children with such difficulties often face barriers in education, social relationships, and self-esteem. Adults may encounter ongoing challenges in professional environments, leading to economic and emotional stress. As the study’s lead author, Dr. Srishti Nayak, emphasized, identifying early markers for these disorders is critical, especially for children, because timely interventions can transform a person’s developmental trajectory.

Listening to Rhythm, Listening to Language

The researchers at Vanderbilt wanted to know whether rhythm perception—the ability to hear and respond to the beat in music—could serve as one such marker. Rhythm skills are not just for drummers or dancers; they are deeply embedded in how our brains process time, sequences, and patterns. And language, at its core, is rhythmic: syllables, pauses, stresses, and cadences all follow patterns that the brain must detect and interpret.

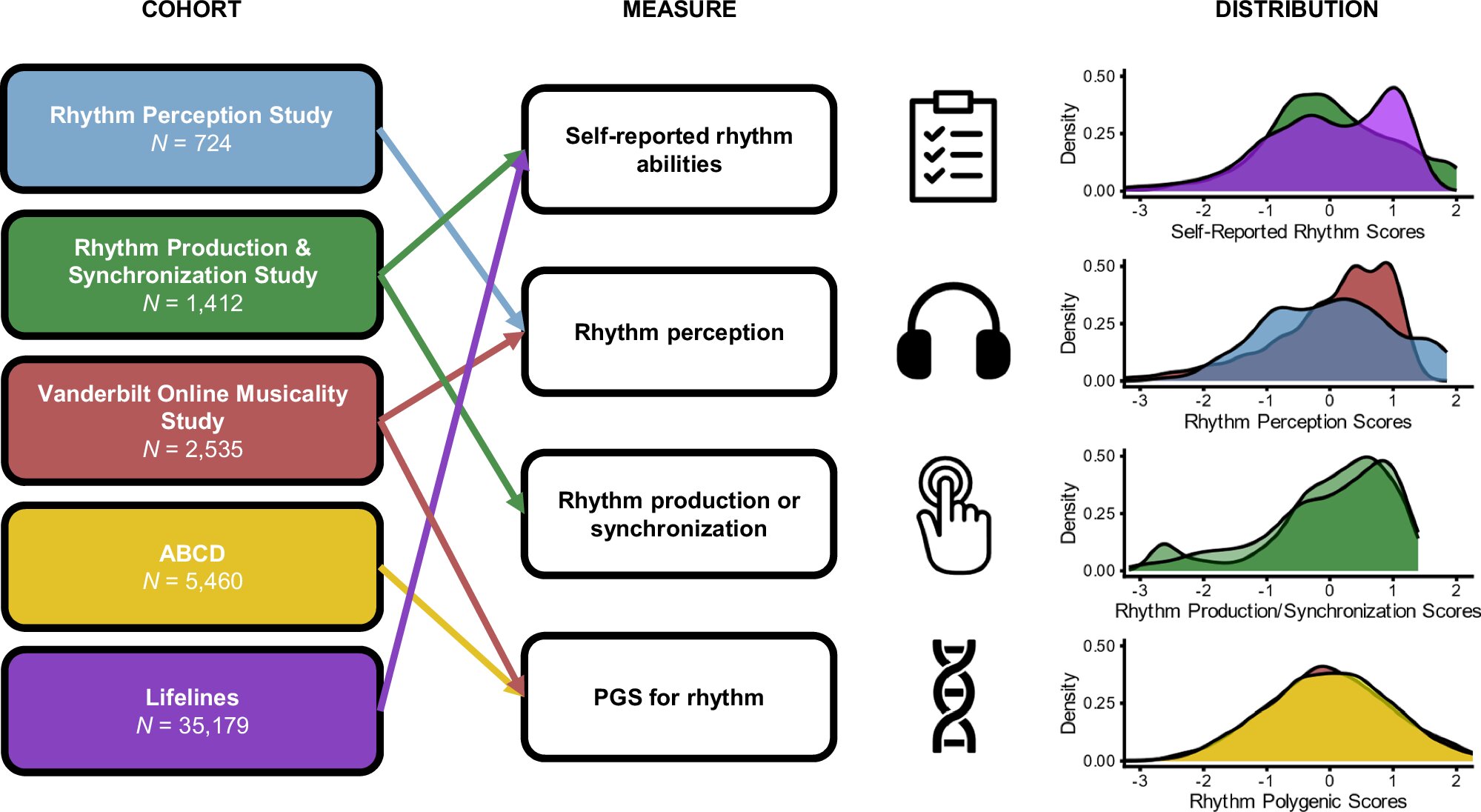

In one of the studies, participants were tested on their ability to perceive small differences in rhythm and to synchronize their movements, such as tapping, with rhythmic cues. They were also asked to self-report their sense of rhythm. The results were clear: weaker rhythm skills were consistently associated with a greater likelihood of developmental communication disorders.

An intriguing exception appeared with stuttering. Unlike dyslexia or developmental language disorder, stuttering did not show the same strong link to poor rhythm perception. Researchers suggested that this may be because people who stutter often receive rhythm-based therapies that, over time, improve their ability to keep time with beats.

The Genetic Connection

The second arm of the research turned to genetics. Could the roots of rhythm perception and language ability be found in our DNA? The answer, it seems, is yes.

By analyzing genetic data, the researchers discovered that certain genetic variations related to rhythm also overlapped with traits linked to reading and language skills. In other words, the ability to perceive rhythm is not only learned through practice and environment but also influenced by inherited biology. Importantly, the study showed that genes connected to rhythm could even predict reading ability—a critical skill that underpins much of education.

This genetic link paints a fascinating picture: our musicality and our ability to communicate are not separate talents but interconnected threads of the same biological fabric.

Beyond the Laboratory: Why This Research Matters

It is easy to take the gifts of speech, reading, and music for granted. But for those who struggle with communication, these abilities are anything but automatic. The Vanderbilt research provides new hope by suggesting that rhythm testing could be used as a simple and powerful diagnostic tool. If a child shows signs of rhythm perception difficulties, clinicians might be able to identify risks for language-related disorders earlier and intervene with tailored therapies.

Music-based interventions may hold particular promise. Rhythm training—through activities like drumming, clapping, or dancing—could strengthen both musical and linguistic abilities. This not only supports children in their education but may also foster confidence, creativity, and joy. As Dr. Nayak explained, the goal is not just to address academic challenges but also to improve broader aspects of mental and physical health, social relationships, and overall well-being.

A Broader View of Human Cognition

The implications of this work extend beyond clinical practice. They touch on fundamental questions about what it means to be human. Why do we sing? Why does rhythm matter so deeply to us? From lullabies to work songs, music has always been intertwined with communication, community, and culture. This research suggests that the connection is not just cultural but biological. Music and language, two of our most defining cognitive abilities, may share a common neural and genetic foundation.

As Dr. Nayak observed, music, speech, and reading are all “hard-wired into our brains.” We do not merely enjoy them; they are part of the way we are built. Recognizing that these domains interact at both behavioral and genetic levels underscores how deeply interconnected our cognitive abilities truly are.

The Human Face of Science

Behind the data and genetic sequencing are real people—researchers, clinicians, and patients—working together to unravel mysteries of the brain. The Vanderbilt Music Cognition Lab, co-directed by Dr. Nayak and Dr. Reyna Gordon, has become a hub for this kind of interdisciplinary exploration. Their work combines neuroscience, genetics, psychology, and musicology, reminding us that science thrives when disciplines merge rather than remain isolated.

Other contributors, like statistical geneticist Dr. Yasmina Mekki, research fellow Dr. Rachana Nitin, and speech-language pathologist Catherine Bush, bring diverse expertise to the table. Their collaboration exemplifies modern science’s greatest strength: the ability to weave together insights from different fields to tackle problems that no single discipline can solve alone.

Toward a Future in Harmony

The findings from these studies are not the end of the story but the beginning of new avenues for research and treatment. Future studies may explore how rhythm training can be implemented on a larger scale in schools and clinics, or how genetic screening might complement behavioral testing to identify at-risk children even earlier.

On a broader scale, this research invites us to think differently about the relationship between art and science. Music is not just entertainment—it is a key to understanding the mind. By listening closely to the rhythms within us, we may unlock new ways to nurture communication, connection, and human potential.

Conclusion

The Vanderbilt study reminds us that the human brain is a symphony of interconnected abilities. Musical rhythm, far from being a niche skill, is bound up with the way we learn to speak, read, and communicate. Its rhythms echo in our genes, shaping how we engage with the world.

For children struggling with developmental language or reading disorders, this research offers both scientific insight and practical hope. Rhythm may become not just a diagnostic marker but a therapeutic tool—a way to help people find their voices through music.

In the end, music, language, and science are all forms of human expression, all ways of reaching beyond silence toward meaning. To study their connections is to better understand not only disorders of communication but also the extraordinary harmony that makes us who we are.

More information: Srishti Nayak et al, Musical rhythm abilities and risk for developmental speech-language problems and disorders: epidemiological and polygenic associations, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-60867-2