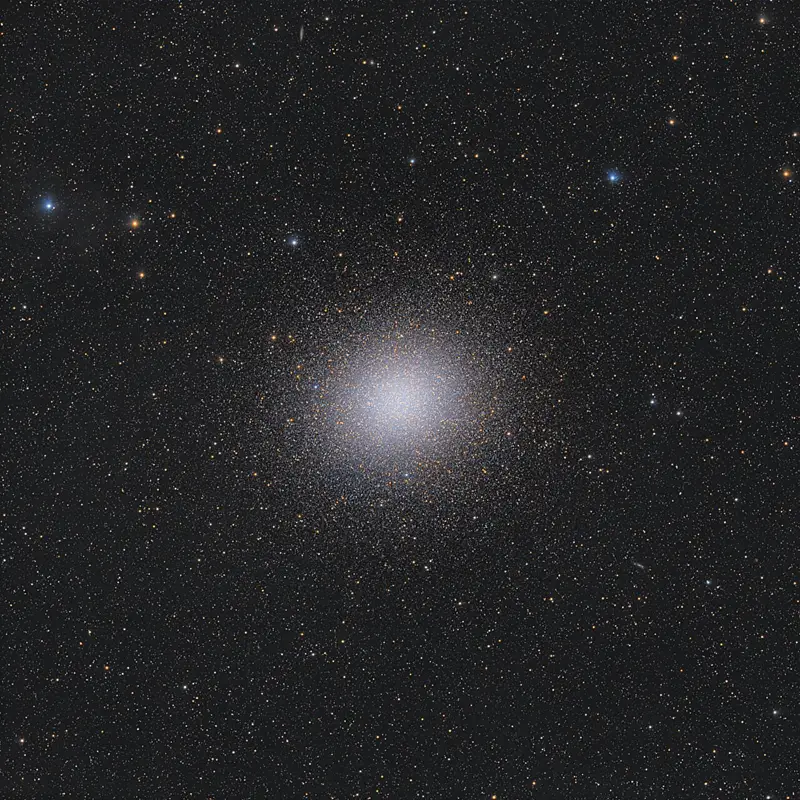

Omega Centauri hangs over the southern sky like a celestial city, immense and crowded, a dense sphere packed with roughly ten million stars. It is the Milky Way’s largest and brightest globular cluster, a place where stars are pressed so tightly together that the space between them feels almost claustrophobic on a cosmic scale. For years, astronomers have suspected that something powerful lurks at its heart, something unseen yet influential enough to shape the motion of stars deep in the cluster’s core.

Earlier this year, that suspicion sharpened into something closer to conviction. Astronomers studying Omega Centauri uncovered evidence that an intermediate mass black hole may be hiding there, betrayed not by light, but by motion. Seven stars near the cluster’s center were found racing through space at astonishing speeds. By all expectations, they should have broken free and flown away. Instead, they remained bound, as if an invisible anchor were holding them fast.

The only explanation that fit was gravity. Something massive enough to corral those stars had to be present, and the calculations pointed toward a black hole with at least 8,200 times the mass of the Sun, and possibly as much as 47,000 solar masses. It was a thrilling clue in a long-standing cosmic mystery. But evidence from motion alone was not enough. Astronomers wanted to find the black hole itself.

The Missing Link That Astronomers Keep Chasing

Intermediate mass black holes occupy a strange and frustrating gap in our understanding of the universe. Stellar mass black holes are familiar outcomes of dying stars, typically weighing up to a few hundred times the mass of the Sun. At the opposite extreme are supermassive black holes, monstrous objects millions or billions of times more massive than our star, anchoring the centers of galaxies.

Between these two populations lies a vast range of possible masses that seem strangely empty. Intermediate mass black holes are expected to exist, yet only a handful of candidates have ever been identified, and confirming them is notoriously difficult. They are thought to be stepping stones in black hole evolution, clues to how small black holes grow into the giants that dominate galactic cores.

If Omega Centauri truly hosts one, it would be a rare and valuable example. Its existence could help explain how black holes grow and how galaxies assemble over cosmic time. The stakes were high, and the search for direct evidence became urgent.

Seven Stars That Should Have Escaped

The case for a hidden black hole began with patience. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, researchers tracked the motions of 1.4 million stars in Omega Centauri over a span of two decades. This long-term view allowed them to detect subtle changes in stellar paths, especially near the cluster’s crowded center.

Among all those stars, seven stood out. They were moving so fast that, under normal circumstances, nothing within the cluster should be able to hold them. Yet they remained trapped, circling the center instead of fleeing into interstellar space. Gravity was clearly at work, and not the gentle collective pull of ordinary stars.

The simplest explanation was a single, massive object exerting a powerful gravitational grip. The numbers pointed toward an intermediate mass black hole. Still, this was indirect evidence. Astronomers wanted confirmation through another channel, one that could reveal the black hole more directly.

Listening for a Signal in the Dark

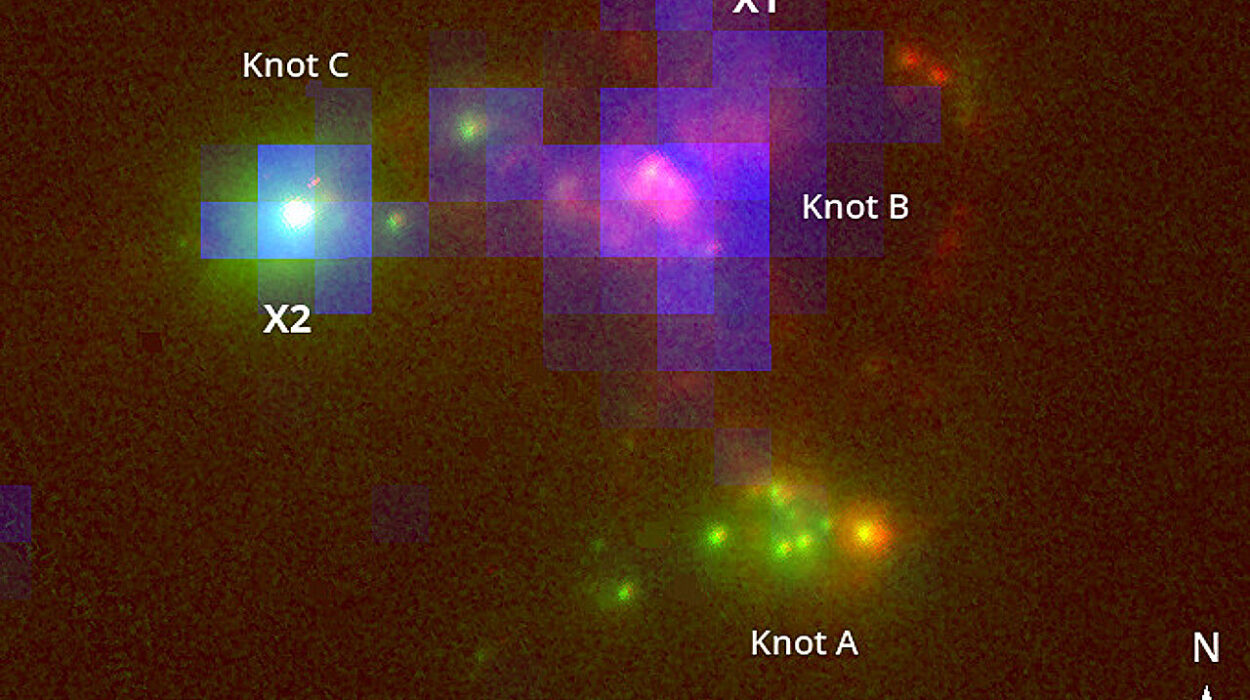

That task fell to Angiraben Mahida and colleagues, who decided to search not for motion, but for soundless whispers in radio waves. Black holes themselves emit no light, but when they feed, they announce their presence. Gas and dust falling inward form a hot accretion disk, heating up and radiating energy across the electromagnetic spectrum. Radio waves are often part of that emission, especially when material spirals toward a black hole.

To listen for this signature, the team turned to the Australia Telescope Compact Array. They aimed the radio dishes at Omega Centauri’s central region for approximately 170 hours, patiently gathering data. The result was the most sensitive radio image of the cluster ever obtained, reaching a sensitivity of 1.1 microjanskys at 7.25 gigahertz.

If a black hole was feeding there, even quietly, this observation should have revealed it. Astronomers waited for a faint glow, a subtle signal rising out of the cosmic background.

Nothing appeared.

The Silence at the Center

The radio image showed no emission at any of the proposed cluster centers where the black hole should reside. The region was silent. No radio glow, no telltale whisper of an accretion disk. The discovery was not a detection, but a non-detection, and that absence itself carried meaning.

The findings, published on the arXiv preprint server, do not rule out the existence of the black hole. Instead, they paint a picture of an object that is extraordinarily quiet. Using the fundamental plane of black hole activity, a relationship that links a black hole’s mass with its radio and X-ray luminosity, the researchers translated silence into limits.

Their calculations show that if an intermediate mass black hole exists in Omega Centauri, it must be accreting matter with extremely low efficiency. The upper limit is roughly 0.004, meaning less than half a percent of the rest mass energy of any infalling material is converted into radiation. In cosmic terms, this black hole would be starving.

A Black Hole in a Cosmic Desert

This extreme quietness may not be surprising once Omega Centauri’s past is considered. The cluster is thought to be the stripped core of a dwarf galaxy that the Milky Way consumed billions of years ago. In that violent process, gas and dust would have been torn away, leaving behind a dense stellar remnant with little raw material left to feed a central black hole.

Unlike the gas-rich environments that surround supermassive black holes in active galaxies, or the close stellar companions that nourish stellar mass black holes, this intermediate mass black hole appears to live in isolation. Its surroundings offer little fuel. Without gas to consume, it produces no bright disk, no jets, no radio glow. It exists, if it exists at all, in near-total silence.

This makes it incredibly difficult to confirm. The very environment that may have allowed the black hole to survive for billions of years now hides it from view.

Why This Quiet Result Matters

At first glance, finding nothing might seem disappointing. But in science, silence can be as informative as a signal. This study places some of the strongest constraints yet on how an intermediate mass black hole in Omega Centauri would behave. It shows that such an object could remain effectively invisible, even under the most sensitive radio scrutiny, simply because it has nothing to eat.

This result reshapes how astronomers think about searching for intermediate mass black holes. It suggests that many may be hiding in plain sight, detectable through their gravitational influence but silent across the electromagnetic spectrum. If so, the universe may contain far more of these elusive objects than currently confirmed.

By demonstrating the limits of radio detection in a gas-poor environment, this research sharpens future strategies and deepens our understanding of black hole growth. It reminds us that the universe does not always announce its secrets with fireworks. Sometimes, the most profound discoveries are whispered through absence, waiting for us to learn how to listen.

More information: Angiraben D. Mahida et al, No evidence for accretion around the intermediate-mass black hole in Omega Centauri, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.09649