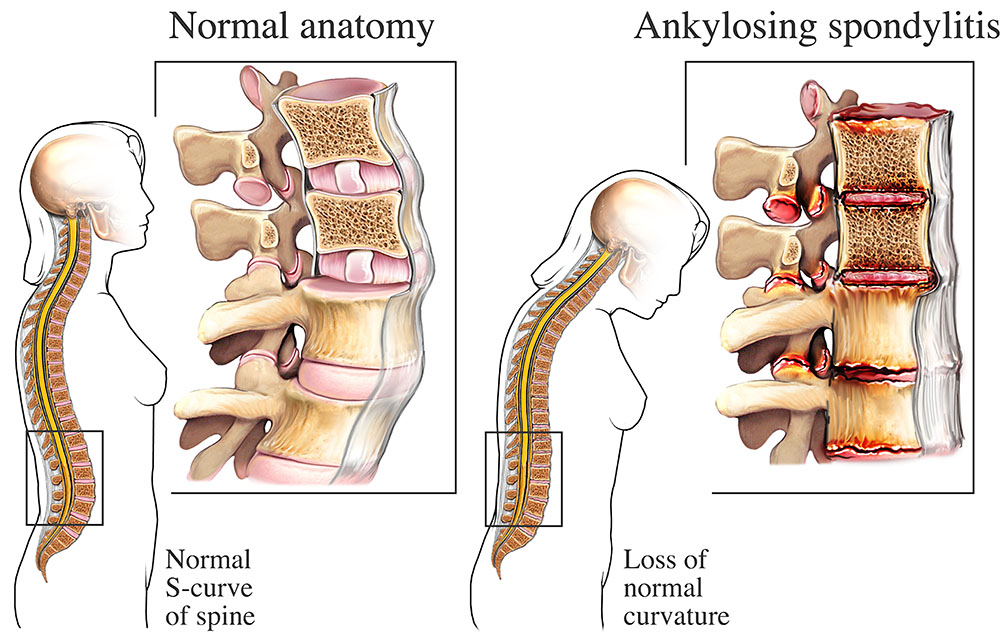

There are few things more liberating than the ability to twist, bend, and stretch freely. Our spine—composed of 33 vertebrae—is a marvel of biological engineering, offering both structure and flexibility. But in ankylosing spondylitis, this fluid mobility begins to harden, quite literally, into a rigid column. Over time, the spine can fuse together in a straight, immovable line, turning what should be supple and adaptable into something more like a rod of bone.

Ankylosing spondylitis, often abbreviated as AS, is a chronic inflammatory disease that primarily targets the axial skeleton—the spine and pelvis. Though its effects ripple throughout the body, its main battleground is the sacroiliac joints, located where the spine meets the pelvis. From there, the inflammation can spread upward, eventually reaching the ribs, chest, and neck. The condition not only causes pain and stiffness but, in its more advanced stages, can dramatically reshape posture and restrict breathing. What makes AS uniquely complex is that it doesn’t just involve bones and joints—it’s a disease of the immune system, misdirected and persistent.

Understanding the Nature of Inflammation

To grasp what ankylosing spondylitis does to the body, it’s important to understand inflammation not as a symptom, but as a mechanism. Normally, inflammation is part of our immune system’s healing toolkit. When you sprain an ankle or cut your hand, the area becomes swollen, red, and warm. That’s inflammation bringing immune cells to clean up damage and promote repair.

In AS, however, the immune system is acting on faulty orders. It mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues, particularly where tendons and ligaments anchor into bone. These areas—called entheses—become hotbeds of chronic inflammation. The body, in its attempt to heal what it wrongly perceives as injury, begins depositing new bone. This cycle repeats: inflammation damages tissue, the body lays down bone, and over time, joints lose flexibility. Eventually, bones may fuse entirely in a process known as ankylosis.

This is the paradox of AS: the body’s healing response is what causes harm. It is not degeneration, like in osteoarthritis, but rather excess growth in the wrong places. The result is not erosion but entombment of mobility.

Who Gets Ankylosing Spondylitis

AS doesn’t strike at random, but it also doesn’t follow a simple pattern. It most commonly begins in early adulthood, typically between ages 15 and 35. While both men and women can develop the condition, it has long been considered more common and more severe in men. Recent studies suggest women are underdiagnosed or diagnosed later because their symptoms may differ—they often have more peripheral joint involvement and less obvious spinal changes on X-rays.

There’s also a strong genetic component. The gene most commonly associated with AS is HLA-B27, a human leukocyte antigen found in the immune system. Around 90 percent of people with AS in European populations test positive for HLA-B27, though having the gene does not guarantee disease. Many people carry HLA-B27 and never develop AS, while some with AS test negative. The gene is a piece of the puzzle, not the whole picture.

Environmental triggers are suspected, too—perhaps infections or biomechanical stress act as catalysts in genetically susceptible individuals. But no single cause has been pinned down. Like many autoimmune diseases, AS arises from a complex interplay of genes, immunity, and external factors, its roots tangled and elusive.

The Early Whispers of a Silent Condition

The early symptoms of AS are insidious. Back pain is a common ailment for nearly everyone at some point, and that’s what makes AS so difficult to catch in its earliest phase. But the back pain of AS has particular characteristics. It usually begins gradually, often in the lower back or buttocks. Rather than worsening with activity, as in mechanical back pain, AS tends to improve with movement and worsen with rest. Many patients report waking in the second half of the night with deep, aching stiffness that only gets better once they start moving.

This stiffness is more than discomfort—it feels like a glue binding your spine in place after periods of inactivity. Morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes is common, and the first few hours of the day may feel like wading through molasses. Over time, this inflammation may migrate up the spine and even reach the rib cage, limiting expansion and making deep breathing painful.

Fatigue is another hallmark. Not the tiredness that follows exertion, but a bone-deep weariness that can feel inexplicable. It is the kind of fatigue that makes every task feel monumental. The inflammation in AS doesn’t confine itself to the back; it influences the whole body, sapping energy and affecting sleep, mood, and concentration.

Diagnosing a Disease That Hides in Plain Sight

Because its symptoms overlap with many other conditions, AS is often misdiagnosed or missed altogether. Many patients spend years navigating a maze of specialists before receiving a correct diagnosis. Standard X-rays may not show changes in the sacroiliac joints until damage has already occurred. By then, irreversible structural changes may be visible, but much of the early inflammatory activity remains unseen.

Modern imaging techniques have revolutionized this. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect inflammation in the sacroiliac joints even before bone damage occurs, allowing earlier diagnosis. Blood tests for HLA-B27, markers of inflammation like C-reactive protein (CRP), and clinical questionnaires about symptoms can guide diagnosis, but there’s no single test for AS. It is still a diagnosis of pattern recognition, requiring both technology and clinical acumen.

Because early detection is critical for managing progression, increasing awareness among primary care doctors, physical therapists, and chiropractors—often the first people to see a patient with back pain—has become a public health goal.

More Than Just a Spinal Disease

AS doesn’t restrict its havoc to the spine. It is a systemic disease, capable of affecting many parts of the body. One of the most common extra-articular manifestations is uveitis—inflammation of the eye’s middle layer. Uveitis can cause redness, pain, sensitivity to light, and blurred vision, and it may recur frequently if not controlled.

Other potential complications include inflammatory bowel disease, particularly Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, which are more common in people with AS. The skin is sometimes involved as well—psoriasis may coexist or emerge in variant forms of the disease. The heart and lungs can be affected in rare cases, with inflammation leading to aortic valve problems or reduced lung capacity due to chest wall stiffness.

This wide-ranging impact means AS is not just a disease of joints—it’s a disorder of the immune system with the spine as its central arena.

The Mechanics of Movement and the Importance of Physical Therapy

For a disease that thrives on immobility, movement is the antidote. Regular exercise is not just recommended for people with AS—it’s essential. Physical therapy helps preserve spinal flexibility and posture, while preventing the development of deformities like kyphosis, a forward curvature that leads to a hunched stance.

The ideal exercise regimen for someone with AS includes stretching, range-of-motion routines, posture training, and aerobic activity. Swimming is particularly beneficial, offering resistance without strain. Even gentle yoga or tai chi can be powerful tools, keeping joints mobile and promoting body awareness.

In addition to movement, physical therapy can help patients manage pain and learn techniques for modifying daily activities. As stiffness increases, everyday tasks—from tying shoes to driving—can become increasingly difficult. Learning how to navigate life with a stiffening spine requires creativity, resilience, and sometimes assistance from adaptive tools.

Medications That Tame the Fire

Modern treatment of AS focuses on taming the immune response. The first line of treatment is typically nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as naproxen or indomethacin. These help reduce pain and stiffness but do not halt the disease’s progression.

When NSAIDs are not enough, biologic medications come into play. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, like adalimumab or etanercept, have revolutionized AS management by targeting specific molecules involved in inflammation. More recently, a new class of biologics—interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitors—has expanded options. These drugs are not cures, but they can dramatically reduce symptoms, prevent new bone formation, and improve quality of life.

The decision to begin biologics is not taken lightly. They are expensive, require ongoing monitoring, and may increase susceptibility to infections. But for many patients, they offer the most effective tool against a disease that can otherwise steal years of mobility and vitality.

Living with a Spine That Feels Like Stone

Chronic disease is not just a medical challenge—it’s a psychological and emotional one. Living with ankylosing spondylitis means adapting to unpredictability. Symptoms may flare or subside without warning. Plans may need to be changed or canceled. Relationships and work life may be impacted.

Support becomes essential—whether through therapy, support groups, or online communities. The isolation of chronic illness can be profound, and simply knowing that others understand the strange stiffness, the invisible fatigue, the frustration of being dismissed because you look “fine”—can offer comfort and strength.

Mental health care is a vital but often neglected part of managing AS. Depression and anxiety are more common among those with chronic inflammation. Addressing these aspects openly can significantly improve not just mood, but overall physical health and engagement in treatment.

Research on the Horizon and Hope for the Future

While there is no cure for ankylosing spondylitis yet, the landscape of research is rapidly evolving. Scientists are uncovering more about the genetic and immunological underpinnings of the disease. Studies are exploring how gut microbiota may influence inflammation, and how diet, lifestyle, and stress impact disease activity.

Clinical trials are ongoing for new biologics and small-molecule therapies that may offer alternatives with fewer side effects or better efficacy. Researchers are also developing predictive tools to identify who is most likely to develop AS among those who carry the HLA-B27 gene. Earlier diagnosis means earlier treatment—and better outcomes.

In parallel, technological innovations are helping patients better monitor their condition. Smartphone apps, wearable devices, and telehealth consultations are bringing a more personalized, responsive approach to managing chronic illness.

Embracing Adaptation Over Resignation

Ankylosing spondylitis is not a disease that yields easily. It requires vigilance, flexibility, and perseverance. But it is not a hopeless diagnosis. With modern treatments, informed self-care, and a proactive medical team, many people with AS live full, active lives.

Adaptation becomes the central theme—learning to move differently, rest strategically, advocate for oneself, and rebuild a life around shifting limitations. It’s not about surrendering to stiffness but confronting it with intelligence, tenacity, and sometimes humor.

The spine may try to stiffen, but the human spirit can remain unyielding. And in that resistance, in that stubborn refusal to give up the joy of motion and meaning, lies the truest form of resilience.