We often take the mechanics of motion for granted. Every time you lift a grocery bag, throw a ball, or even swipe your phone, your body is executing a marvel of coordinated action. Beneath the skin, muscles pull on tendons, tendons tug on bones, and tiny fluid-filled sacs cushion the rubbing parts to keep everything running smoothly. But this elegant choreography can falter when one element is overworked.

Tendonitis and bursitis are two of the most common results of such failure—twin afflictions of the musculoskeletal system that arise not from dramatic trauma, but from repetition. They don’t appear suddenly with the snap of a ligament or the fracture of a bone. Instead, they creep in silently, the body’s protest against persistent strain.

Both conditions are known as overuse injuries, often appearing in athletes, laborers, musicians, and increasingly, desk workers tethered to keyboards and smartphones. Though they may sound mundane compared to broken bones or torn ACLs, they can be surprisingly disruptive, and their mechanisms offer a window into the intimate workings of the body’s motion machinery.

The Anatomy of Tendons and Bursae

To understand tendonitis and bursitis, we first need to know what tendons and bursae are and what they do.

Tendons are strong, fibrous cords of collagen-rich connective tissue that tether muscle to bone. Their job is to transmit the force generated by muscle contraction to the skeleton, allowing movement. Unlike muscles, tendons do not contract; they are passive transmitters of force. But they’re not inert—they bend, stretch slightly, and must withstand enormous loads, especially during rapid or repetitive activity.

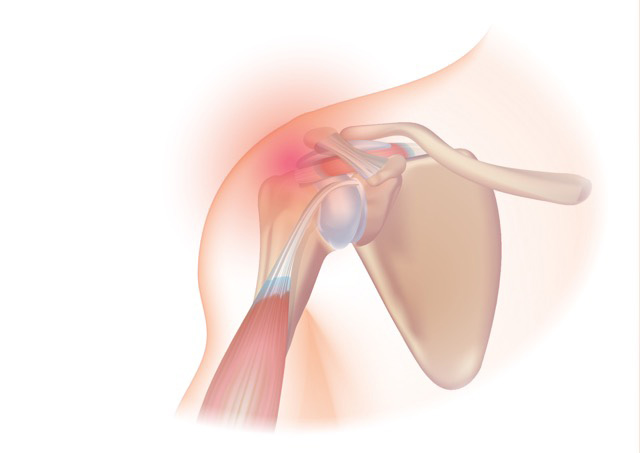

Bursae, on the other hand, are small, fluid-filled sacs that act as cushions between bones and soft tissues such as skin, muscles, or tendons. There are more than 150 bursae in the human body, and they are typically located near major joints—the shoulders, elbows, hips, and knees. Their role is simple but crucial: they reduce friction. Like tiny water balloons, they allow moving parts to glide past one another with minimal resistance.

Both structures exist in a finely tuned environment where movement should be fluid and pain-free. When things go wrong, however, inflammation can strike either—or both—leading to tendonitis or bursitis.

What Happens When Tendons Cry Out

Tendonitis, also spelled tendinitis, is an inflammatory condition of the tendon. It typically arises when a tendon is subjected to more strain than it can handle, especially in a repetitive manner.

The classic picture is familiar: the tennis player with a sore elbow, the runner with an aching Achilles, or the office worker with wrist pain from hours of typing. These are not injuries caused by one bad move but by many small ones—the repeated microtrauma of everyday tasks or sports that eventually overpowers the tendon’s ability to repair itself.

In healthy tendons, microscopic damage is continuously repaired by a network of cells called tenocytes. These cells maintain the structure and health of the tendon by managing collagen turnover. But when the rate of damage exceeds the rate of repair, inflammation ensues. Swelling, pain, and limited mobility follow.

Interestingly, research has shown that true inflammation in the traditional immune sense (with white blood cell infiltration) is not always present in what we call tendonitis. Some experts prefer the term “tendinopathy” or “tendinosis” for chronic cases, where the tendon degenerates rather than inflames. Still, the pain is real, and the functional decline can be significant.

The Quiet Rebellion of the Bursae

Bursitis is the inflammation of a bursa. Like tendonitis, it often results from repetitive motion or pressure. For example, spending hours kneeling on a hard surface can irritate the prepatellar bursa in the knee, leading to what is sometimes called “housemaid’s knee.” Repeated overhead lifting can inflame the subacromial bursa in the shoulder.

Sometimes bursitis occurs from direct trauma, like a fall on the elbow, or from infection, in which case it is called septic bursitis. But more commonly, it is non-infectious and stems from irritation due to overuse or underlying joint problems.

When a bursa becomes inflamed, it swells with extra fluid, leading to pain, tenderness, and decreased joint range of motion. The symptoms can mimic other joint problems like arthritis, making diagnosis challenging without imaging or clinical expertise.

Common Sites of Injury in the Modern World

Certain areas of the body are more prone to tendonitis and bursitis due to their workload and anatomical design.

The shoulder, with its extraordinary range of motion, is a prime target. The rotator cuff tendons are frequently inflamed in athletes and manual laborers. The nearby subacromial bursa is also commonly affected, often in tandem with rotator cuff issues.

The elbow is another frequent site. “Tennis elbow” (lateral epicondylitis) affects the tendons on the outer side of the elbow, while “golfer’s elbow” (medial epicondylitis) affects the inner side. Though named after sports, these injuries are common in office workers, plumbers, and painters alike.

In the hip, the trochanteric bursa can become inflamed, particularly in runners and older adults. The Achilles tendon at the back of the ankle is another hotspot, especially in runners or those who suddenly ramp up physical activity.

Even the wrist and thumb can become victims—conditions like De Quervain’s tenosynovitis often affect new parents who frequently lift their babies in awkward positions, as well as anyone who engages in repetitive hand movements.

Why Repetition Is the Root of the Problem

The body thrives on movement—but only in the right doses. Tendons and bursae are designed to handle dynamic loads, but not relentless, unchanging stress.

When a movement is repeated without sufficient rest or variation, the mechanical stress on the tissues accumulates. This is especially problematic when posture, ergonomics, or technique are poor. Over time, even a small mechanical inefficiency—an odd angle of the wrist, a slouched shoulder, an improperly fitting shoe—can lead to tissue breakdown.

Modern life often encourages exactly the kind of behavior that leads to overuse. We sit for hours at desks, often in poor positions. We click mice and tap keyboards with microscopic but constant motions. We text, swipe, and scroll. And when we exercise, we often do so with a narrow focus—running the same route, lifting the same weights, performing the same strokes or swings.

The lack of variety, rest, and balance sets the stage for chronic stress injuries. Tendonitis and bursitis are not signs of aging or weakness—they are red flags of imbalance, of motion gone awry.

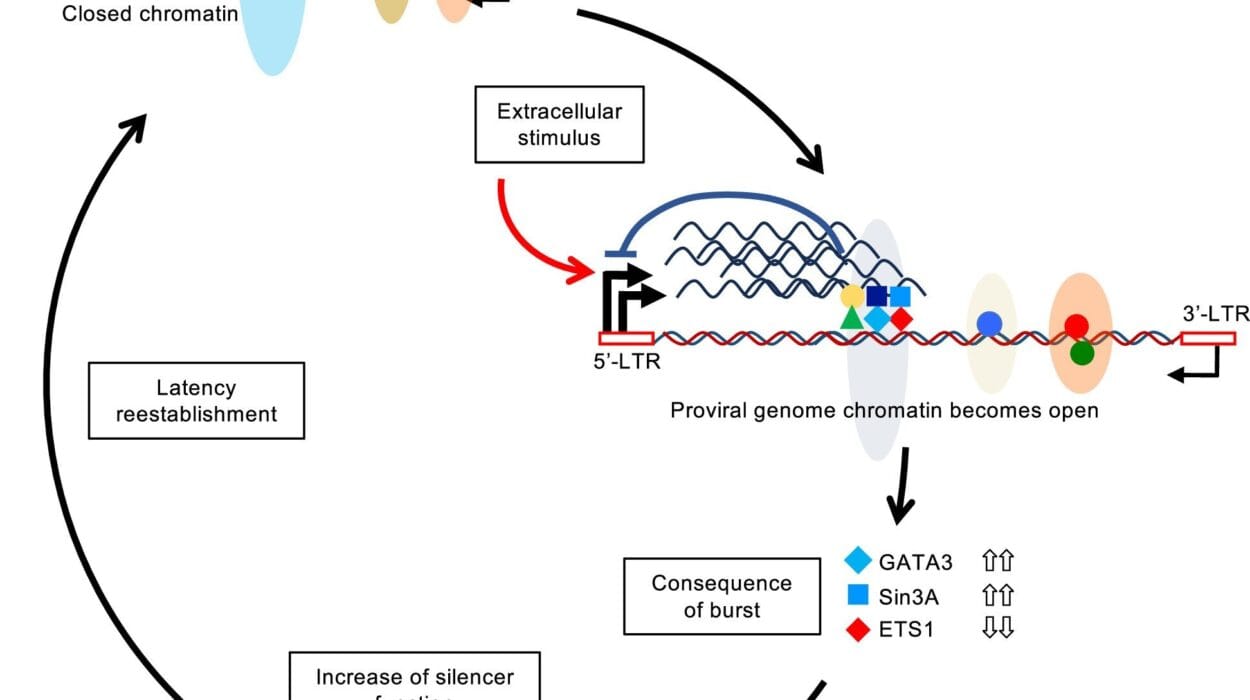

How the Body Tries to Heal

When overuse causes microdamage, the body responds with inflammation. Blood vessels dilate, immune cells rush in, and pain signals are triggered. In the short term, this is protective—pain discourages further use, giving the tissue a chance to heal.

But if the triggering activity continues, the inflammation may become chronic. In tendons, the collagen fibers can begin to fray. In bursae, the fluid may accumulate excessively, distending the sac and crowding nearby tissues. Over time, these changes can lead to scar formation, reduced flexibility, and persistent discomfort.

Rest is the body’s first instinct, and for good reason. However, complete immobilization can lead to stiffness and weakness. The ideal treatment requires a balance of rest and targeted activity—a delicate negotiation between movement and stillness.

Diagnosis in a Sea of Similar Symptoms

Because many conditions can cause joint or soft tissue pain, diagnosing tendonitis or bursitis can be a challenge. Both present with pain, tenderness, swelling, and restricted movement. Differentiating them from arthritis, fractures, nerve entrapments, or other inflammatory conditions often requires a careful history and physical exam.

Imaging can help. Ultrasound can visualize inflamed tendons or bursae, while MRI can provide detailed views of soft tissue structures. In cases of suspected infection or autoimmune disease, blood tests may be used.

Yet in many cases, the diagnosis is clinical—a matter of piecing together the story of the pain. When it started, what triggers it, which movements are difficult, and how the body has responded. Like a detective, the clinician must listen to the body’s clues.

Healing Through Movement and Medicine

Treatment for tendonitis and bursitis follows the same general principle: reduce inflammation, allow healing, and restore function.

In the acute phase, rest, ice, compression, and elevation—known as the RICE protocol—can reduce swelling and pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen may also help.

But rest alone is rarely sufficient. Once pain begins to subside, gentle stretching and strengthening exercises become crucial. Physical therapy plays a central role in both treatment and prevention. A skilled therapist can assess movement patterns, identify imbalances, and create a program to rehabilitate the affected area while addressing root causes.

In some cases, corticosteroid injections may be used to reduce stubborn inflammation, particularly in bursitis. These injections offer rapid relief but are used cautiously, especially in tendons, where repeated steroid use can weaken the tissue.

Surgery is rarely necessary but may be considered in severe or unresponsive cases—such as tendon tears or chronic bursitis that limits mobility.

Prevention as the Most Powerful Medicine

Perhaps the most important insight from these conditions is the value of prevention. Because tendonitis and bursitis result from repeated strain, they are often avoidable with a few key strategies.

Proper ergonomics at work and during exercise can significantly reduce risk. This means paying attention to posture, equipment setup, and technique. Warming up before activity, taking regular breaks, and cross-training to engage different muscle groups also protect against overuse.

Equally important is listening to the body. Pain is not just a nuisance—it is information. It tells us when something is amiss, when tissues are overloaded, or when rest is needed. Ignoring these signals out of habit, pride, or productivity can turn a minor issue into a major setback.

Strengthening and stretching programs tailored to your lifestyle can help keep tendons and bursae healthy. This is especially vital as we age, since connective tissue loses elasticity and blood flow decreases.

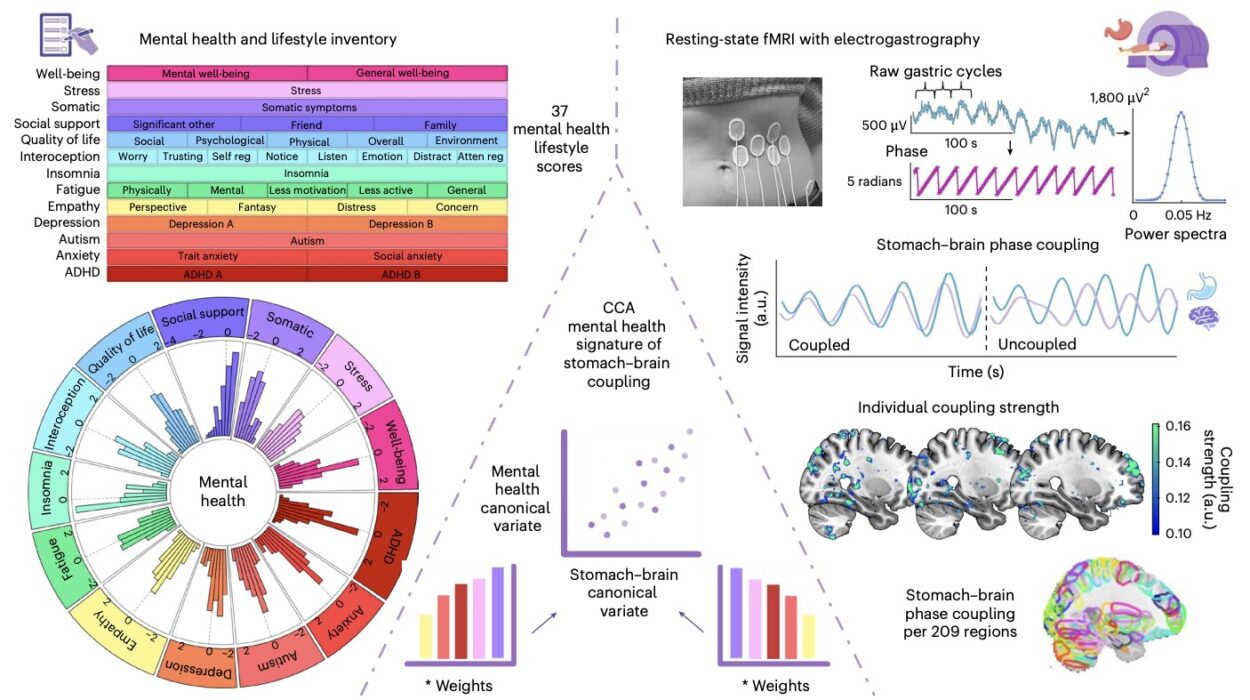

The Mind Body Connection in Chronic Pain

Tendonitis and bursitis are physical conditions, but they are not separate from the emotional life of the person experiencing them. Chronic pain affects mood, sleep, and productivity. It can lead to frustration, anxiety, and even depression.

Conversely, psychological stress can amplify physical pain. The nervous system’s perception of pain is modulated by emotional and cognitive factors. This is not to say the pain is imagined—it is very real—but its intensity and persistence can be influenced by the mind.

Integrative approaches that address both body and mind—such as mindfulness, stress management, and cognitive-behavioral therapy—can be helpful for individuals with persistent pain. In some cases, pain becomes entrenched in neural circuits even after the tissue has healed, creating a cycle that needs to be broken through rehabilitation and neuroplasticity-based therapies.

A Future Where Prevention Is Personalized

As medicine becomes more personalized and technology advances, our understanding of overuse injuries is evolving. Wearable sensors can now monitor joint angles, repetition counts, and muscular activation in real time. Artificial intelligence can detect subtle biomechanical deviations that predispose to injury. Genetic studies may one day reveal individual susceptibilities to tendon degeneration or inflammation.

In elite sports, movement analysis, predictive modeling, and data-driven training are already helping to prevent injury. These tools are gradually becoming accessible to the general public. With proper use, they could help identify risk before pain begins, ushering in an era of proactive rather than reactive care.

Ultimately, the goal is to foster a relationship with our bodies that is sustainable, respectful, and responsive. Tendonitis and bursitis are reminders that even the strongest tissues have limits—and that healing requires attention, adaptation, and care.

Returning to the Joy of Motion

Though they are common and often frustrating, tendonitis and bursitis are rarely permanent. With the right approach, most people make a full recovery and return to their normal activities—sometimes even stronger than before.

These conditions offer not just a challenge, but an opportunity. An opportunity to reassess how we move, how we rest, how we work, and how we care for the intricate machinery of our own bodies.

Motion is life. And when the body sends us a warning, as it does with tendonitis or bursitis, it’s not to punish us—but to teach us. To ask us to listen more closely, move more mindfully, and restore balance to the ever-evolving dance of anatomy and action.