In a quiet office buzzing with fluorescent lights and rows of high-performance computers, Ahmed Abdeen Hamed stared at something remarkable—and unnerving. The artificial intelligence that millions now casually turn to for advice, reassurance, or even medical guidance had just passed a critical scientific test with flying colors. Or had it?

Across the globe, people with a sore throat, a racing heart, or an unexplained ache are skipping the doctor’s waiting room and opening ChatGPT instead. “Do I have cancer?” they ask. “Is this cardiac arrest?” “What does this gene mean?” And while the machine might answer within seconds, the consequences of its words could linger for a lifetime.

Ahmed Abdeen Hamed, a research fellow at Binghamton University’s Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science, wanted to know just how much trust we should place in a generative AI’s response when the stakes are nothing less than life and death. Along with collaborators from Poland’s AGH University of Krakow, Howard University, and the University of Vermont, Hamed launched a study that would push ChatGPT into the heart of medical science—and measure its truthfulness there.

What they found was both thrilling and troubling.

A Surprising Source of Medical Truth

ChatGPT, like all large language models, is designed to predict the next word in a sentence based on an immense sea of data. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it understands what it’s saying—especially when it comes to something as specialized as medicine. So how could it possibly know what’s real and what’s dangerous guesswork?

Hamed wasn’t expecting miracles. He assumed accuracy would be low—maybe 25% if they were lucky. Instead, what he and his team saw was astonishing. The model accurately classified disease names, drug terms, and genetic information at rates as high as 97%. When prompted with questions like “Is BRCA a gene?” or “Is Remdesivir a drug?” ChatGPT consistently offered correct answers.

“It was incredible,” Hamed said. “Absolutely incredible. I was shocked. ChatGPT said cancer is a disease, hypertension is a disease, fever is a symptom, Remdesivir is a drug, and BRCA is a gene related to breast cancer.”

For a tool never formally trained on biomedical databases or ontologies—the structured systems used by professionals to define and organize scientific knowledge—this level of understanding was almost surreal.

The Cracks Beneath the Surface

But like a beautifully painted portrait that starts to flake under close inspection, ChatGPT’s shine dulled when researchers dug deeper.

When it came to symptoms—perhaps the most relatable part of a medical experience—the model faltered. Accuracy dropped to between 49% and 61%. And while that might sound like a coin toss, it could be the difference between comfort and catastrophe for someone relying on the tool in a moment of fear.

The problem seems to stem not from ignorance, but from translation. ChatGPT is trained to sound like your friend—warm, informal, and approachable. But the world of medicine doesn’t speak that way. It uses precise terms drawn from biomedical ontologies, and those terms are rarely the way ordinary people describe what they feel. A “mild, intermittent chest pressure” might be labeled as “angina pectoris” in the medical literature, but few people would ever type that into a chat box.

“The LLM is apparently trying to simplify the definition of these symptoms,” Hamed noted. “Because there is a lot of traffic asking such questions, it started to minimize the formalities of medical language to appeal to those users.”

In other words, it’s adapting to us—and in doing so, sometimes straying further from scientific precision.

The Ghost in the Genome

One discovery in the study wasn’t just concerning—it was downright eerie.

The National Institutes of Health maintains a rigorous, detailed database called GenBank. Each DNA sequence in this database is assigned a unique accession number, such as NM_007294.4 for the BRCA1 gene. These identifiers are like the barcodes of genetic science: they ensure every gene is tracked and unambiguous.

When ChatGPT was asked for these numbers, it didn’t retrieve them. It didn’t say it didn’t know. It simply made them up.

This phenomenon, known as “hallucination,” is a known issue with large language models. But in the realm of medicine—where misinformation can lead someone to delay care or accept false reassurance—hallucination becomes far more than a glitch. It’s a breach of trust.

“That was a major failing,” Hamed admitted. “You can’t just fabricate genetic identifiers and expect the user to know they’re wrong.”

This points to a broader problem. Even when AI seems helpful, it may only be confidently incorrect. And unless you’re an expert, you may never know the difference.

A Vision for Safer AI

Rather than condemn the technology, Hamed sees opportunity. The success of the model in some areas proves its potential. The hallucinations and inaccuracies reveal the need for deeper integration with vetted, structured scientific resources.

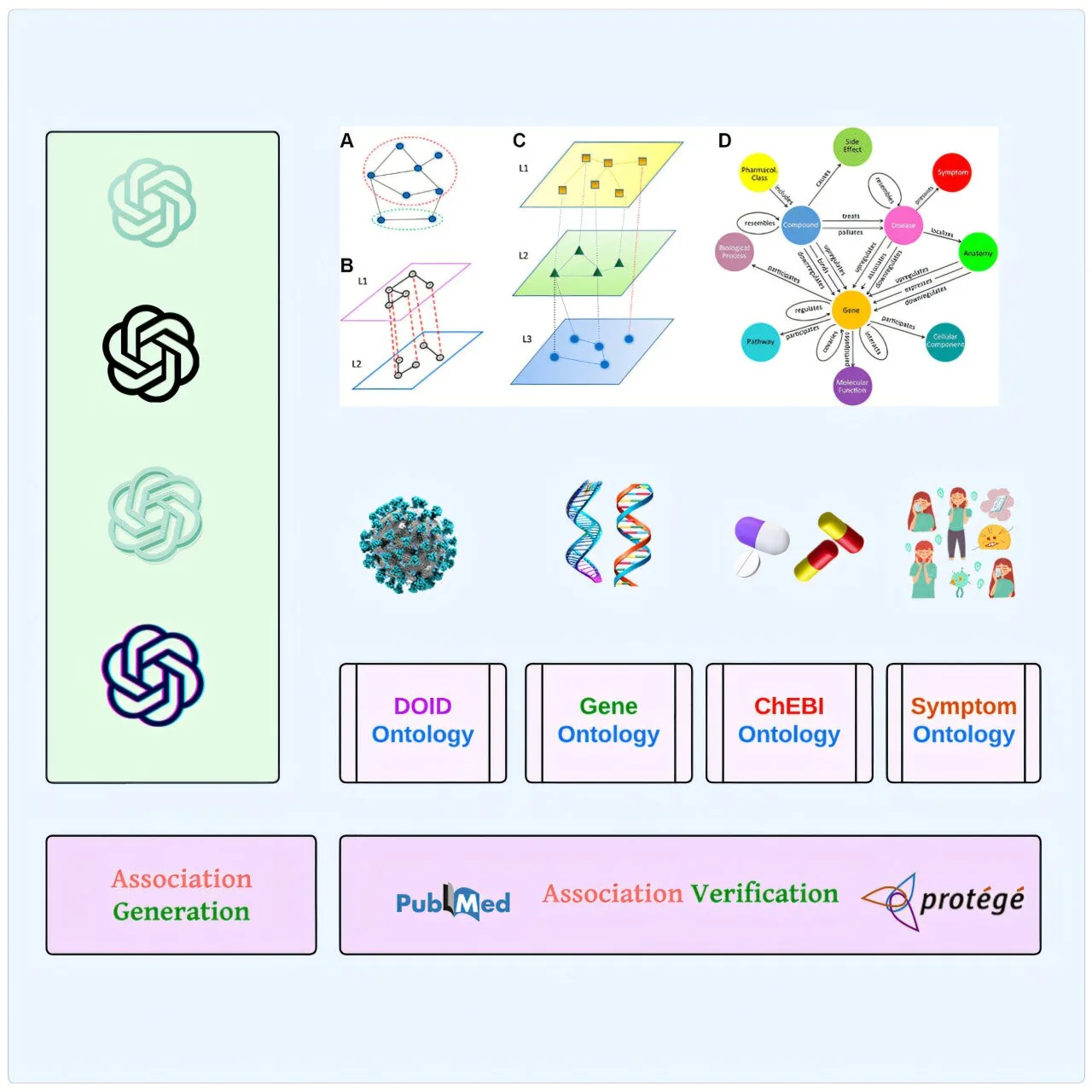

His earlier work—an algorithm called xFakeSci that could detect fraudulent scientific articles with 94% accuracy—laid the foundation for this new endeavor. Now, he envisions a future in which AI like ChatGPT is seamlessly linked to biomedical ontologies, constantly cross-checking its answers against gold-standard databases like GenBank and PubMed.

“Maybe there is an opportunity here,” he said. “We can start introducing these biomedical ontologies to the LLMs, provide much higher accuracy, get rid of hallucinations, and make these tools into something amazing.”

But doing so means accepting that AI is not a mirror of truth—it is a mosaic of probabilities. And like any mosaic, its beauty lies in structure. Without it, even the best intentions fall apart.

The Emotional Cost of Curiosity

It’s tempting to dismiss these findings as technical—numbers and percentages, accuracies and algorithms. But behind every symptom typed into a chatbot is a human being. Someone afraid. Someone hoping for an answer. Someone who, perhaps at 2 a.m., didn’t want to bother anyone but still needed to know: “Am I okay?”

AI offers comfort. It offers speed. But it also offers a mirage. And the most dangerous mirages are the ones that look the most real.

When ChatGPT guesses at a diagnosis, it does so without a heartbeat. It doesn’t know fear. It doesn’t sit in a clinic wondering how to tell a patient they have cancer. It doesn’t feel the ethical weight of a lie.

That’s why studies like this matter so much. Not because AI will replace doctors—most experts agree it won’t—but because it’s already replacing something else: the first point of contact. And if that contact is flawed, what comes next might be too.

Toward a Smarter, Kinder Machine

There’s a strange poetry in training a machine to understand suffering. In making lines of code grasp what it means to ache, to worry, to hope for healing. But if we want AI to serve us in our most vulnerable moments, we must first make sure it knows how not to harm us.

For Hamed, that means more than accuracy—it means alignment with real science, real facts, and real human needs.

“If I am analyzing knowledge,” he said, “I want to make sure that I remove anything that may seem fishy before I build my theories and make something that is not accurate.”

And that’s the heart of this story. Not just whether ChatGPT can tell you what a symptom means—but whether we can build a future where it’s safe to ask.

Reference: Ahmed Abdeen Hamed et al, From knowledge generation to knowledge verification: examining the biomedical generative capabilities of ChatGPT, iScience (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.112492