In the limestone hills of Anhui Province, China, a cluster of ancient teeth is forcing scientists to rethink what they thought they knew about our species’ tangled ancestry. At the Hualongdong site, archaeologists have unearthed human fossil remains dating back more than 300,000 years—and what they reveal is nothing short of extraordinary.

A new study published in the Journal of Human Evolution, led by Professor Wu Xiujie and supported by an international team including researchers from Spain’s Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), describes a set of dental fossils that defy conventional categories. These teeth, some preserved in the skull of a nearly complete cranium, don’t belong neatly to Homo erectus, Homo sapiens, or even the enigmatic Denisovans. Instead, they embody a mosaic of features—some ancient, some surprisingly modern—hinting at a complex evolutionary experiment in Asia that may have played a deeper role in our own story than previously imagined.

A Tooth in Time

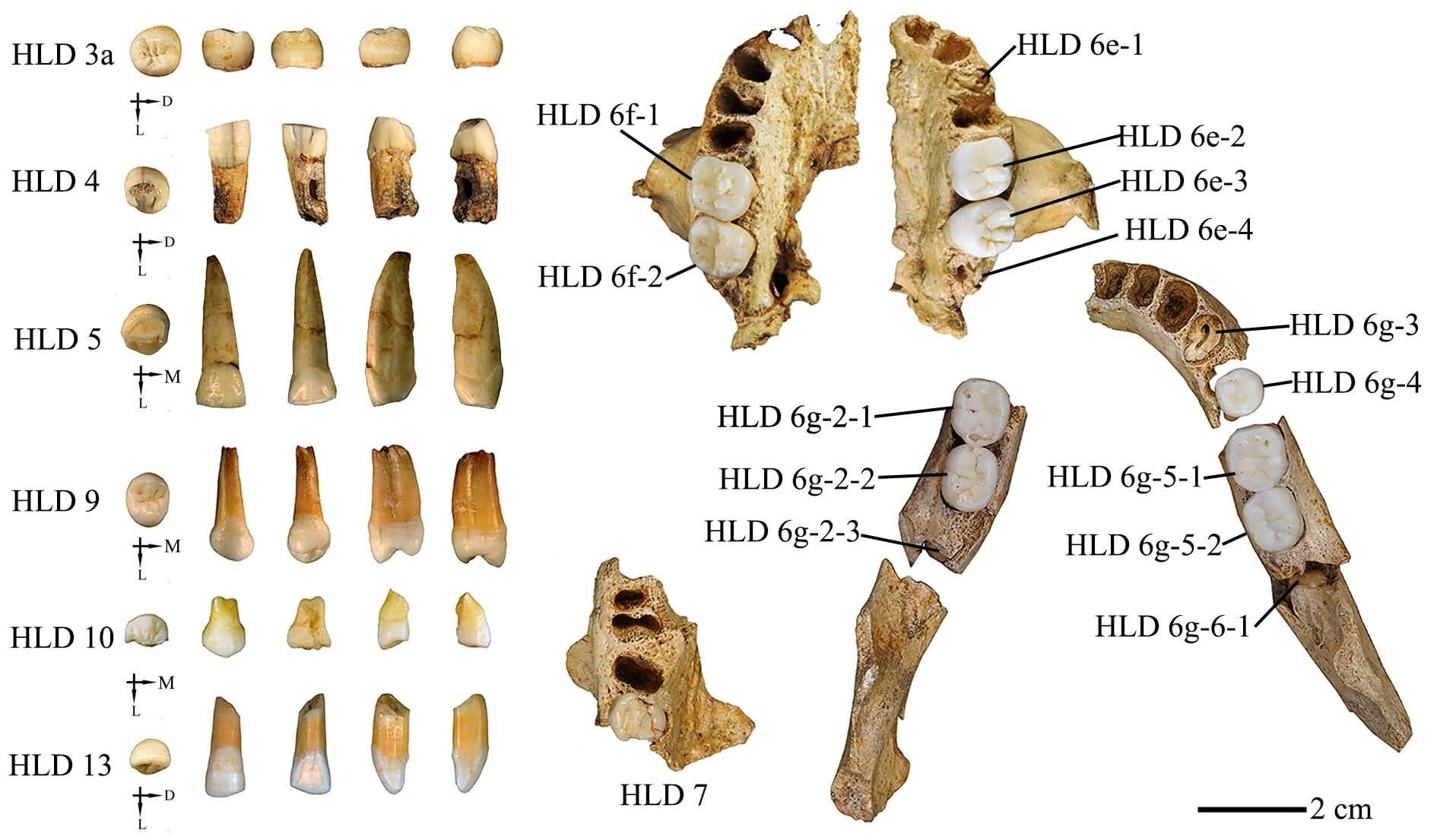

Teeth may seem unremarkable, but to paleoanthropologists, they are evolutionary gold. Their shape, wear, and inner structure carry echoes of diet, development, and species identity. At Hualongdong, the research team conducted a detailed comparative analysis of 21 dental elements, uncovering a startling mix of characteristics.

The fossil teeth possess thick, robust roots—a hallmark of archaic human species like Homo erectus—but they also show a significant reduction in the size of the third molar, or wisdom tooth, a trait associated with modern humans. “It’s a mosaic of primitive and derived traits never seen before—almost as if the evolutionary clock were ticking at different speeds in different parts of the body,” says Dr. María Martinón-Torres, Director of CENIEH and co-author of the study.

The team was particularly struck by what wasn’t present. The dental patterns showed no trace of Neanderthal traits, even though Neanderthals are known to have lived across large parts of Eurasia during this time. This absence suggests that the Hualongdong hominins belonged to a distinct population, possibly a sister lineage to Homo sapiens—one that branched out on its own evolutionary path deep within the heart of Asia.

Ghosts in the Ancestral Tree

For decades, the dominant narrative in human evolution cast Africa as the undisputed cradle of modern humans, with other regions playing more peripheral roles. Asia, in that storyline, was home to Homo erectus and, later, to migrating waves of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. But the Hualongdong fossils challenge that view.

Their anatomy implies a much more intricate picture of hominin diversity in Asia during the Middle Pleistocene. Far from being a quiet cul-de-sac on the evolutionary highway, East Asia may have been a bustling crossroads—where multiple lineages evolved, mingled, and occasionally converged toward modernity on their own terms.

“This discovery reminds us that human evolution was neither linear nor uniform,” says José María Bermúdez de Castro, co-author and honorary researcher at CENIEH. “Asia hosted multiple evolutionary experiments with unique anatomical outcomes.”

One possibility is that the Hualongdong individuals descended from a local population of Homo erectus that began developing modern traits independently—a case of parallel evolution. Another is that they represent a now-extinct branch closely related to Homo sapiens, perhaps even a ghost lineage that once contributed genes to modern humans, but left behind no clear descendants.

The Evolutionary Mosaic

The term “evolutionary mosaic” has become something of a mantra in recent paleoanthropology, but Hualongdong gives it vivid, literal form. While the skull’s facial structure leans toward modernity, with a flat midface and lightly built features, the jaw and teeth pull in the opposite direction—toward ancient forms built for a tougher, rawer diet.

It’s as if nature was experimenting, testing which combinations of traits would be most successful in the changing environments of Pleistocene Asia. These anatomical hybrids might not have looked much like us—or each other—but they show that evolution was not progressing along a single, preordained path.

Crucially, this is not an isolated case. A previous study at Hualongdong revealed a juvenile individual whose features echoed this same mix of modern and archaic traits. Now, with additional adult specimens showing similar patterns, the evidence points to a stable population—a long-lasting evolutionary experiment that deserves its own chapter in the human story.

Rethinking Asia’s Role

Until recently, much of the focus in human origins research has hovered around Europe and Africa, where abundant fossils and genetic data have shaped most of our theories. But sites like Hualongdong, Panxian Dadong, and Jinniushan are pulling back the curtain on a more nuanced tale—one in which Asia may have birthed its own evolutionary innovations, some of which may have left faint traces in our own DNA.

These fossils could also help explain longstanding mysteries, such as the identity of the Denisovans—a shadowy population known almost entirely from a few bones and teeth in Siberia and Tibet. Could the Hualongdong population be part of that broader Denisovan world, or perhaps another, still unnamed branch of humanity?

The truth remains hidden in stone and sediment. But what’s becoming clear is that Asia was not a passive backdrop in the human saga. It was a laboratory of life, where evolution ran multiple experiments in parallel—and sometimes, those experiments came close to producing something very much like us.

A Future Written in Fossils

The study at Hualongdong is the fruit of years of collaboration between the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing and CENIEH in Spain. Led by Professor Wu Xiujie, with key contributions from Martinón-Torres and Bermúdez de Castro, the project demonstrates what can be achieved when international teams bring together their expertise—and their curiosity.

These findings may not rewrite the entire book of human evolution, but they do add bold new chapters. They remind us that our lineage is not a straight line from primitive to advanced, but a branching tree with many twigs—some dead ends, others turning points. The teeth at Hualongdong don’t just tell us who lived there. They whisper of all the ways our species might have been.

As researchers continue to excavate, date, and analyze these ancient bones, one thing is certain: the past is not finished with us yet. With each new find, our understanding of what it means to be human grows deeper, richer—and more beautifully complex.

Reference: Xiujie Wu et al, The hominin teeth from the late Middle Pleistocene Hualongdong site, China, Journal of Human Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103727