Imagine holding a secret that’s been hidden in plain sight for nearly a century — a mysterious fossil waiting silently for its other half to reunite. That’s exactly what happened recently in the fascinating world of paleontology, where a doctoral student’s chance discovery has transformed a long-known but incomplete fossil into a vivid portrait of a new ancient reptile species.

The Tale of Two Fossils: A Century-Old Mystery

Since the 1930s, a peculiar impression of a small reptile had intrigued scientists at the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt. Preserved in the famous Solnhofen limestone slabs, this ancient creature was estimated to have lived about 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic. Its delicate body imprint bore the unmistakable outline of a long-limbed, lizard-like reptile.

Scientists had classified it as Homoeosaurus maximiliani, part of a group known as Rhynchocephalia — a lineage now nearly extinct except for a curious survivor, the tuatara of New Zealand. But without the skeleton, much about this fossil remained a mystery.

Then came the discovery that changed everything.

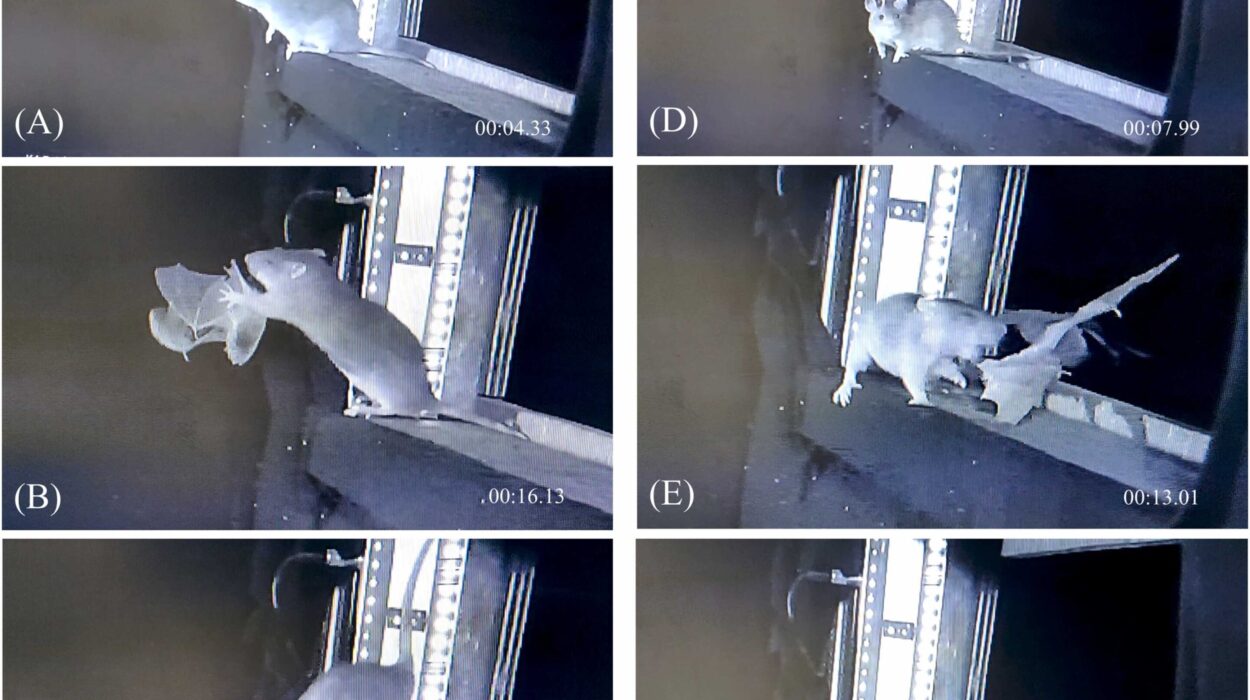

Victor Beccari, a Ph.D. student working at the Bavarian State Collection of Paleontology and Geology and LMU Munich, was studying the Natural History Museum in London’s vast collections when he stumbled upon a fossil that resembled the Frankfurt specimen. This wasn’t just any fossil — it was the counterslab, the other half of the limestone slab that perfectly matched the Frankfurt fossil, containing the actual bones missing from the body impression.

For nearly a hundred years, these two pieces had been separated, hidden in different museums, their connection lost to time.

Reuniting the Past: The Birth of Sphenodraco scandentis

When Beccari and his international team pieced together the two slabs, a startling revelation emerged. This was no ordinary reptile; it was a new species entirely, which they named Sphenodraco scandentis. The name reflects its lizard-like appearance (Sphenodraco means “wedge dragon”) and hints at its climbing prowess (scandentis means “climber”).

This discovery was not just a matter of classification — it opened a window into the life and habitat of an ancient reptile that lived alongside dinosaurs in the Jurassic period. The fossils came from the limestone-rich Altmühl valley between Solnhofen and Kelheim in Bavaria, a place world-famous for its exquisitely preserved fossils, including the iconic Archaeopteryx, the earliest known bird.

A Tree-Climbing Reptile of the Jurassic

What made Sphenodraco truly unique was its long limbs relative to its small body. This was unusual compared to other known rhynchocephalians. By comparing Sphenodraco’s anatomy with modern lizards of similar build, the researchers proposed an exciting lifestyle: this ancient reptile was likely an adept climber, spending much of its life navigating the trees of the Jurassic archipelago.

This would make Sphenodraco potentially the first known arboreal species from its group — a remarkable adaptation in a lineage mostly known for ground-dwelling species. Its slender, elongated limbs would have helped it grasp branches and move agilely through foliage, escaping predators and hunting for food in the treetops.

Professor Oliver Rauhut, a renowned paleontologist and co-author of the study, emphasized the significance of this find. “The Solnhofen Archipelago is famous for its diverse rhynchocephalian fauna. Every new fossil, like Sphenodraco scandentis, sheds light on the evolution and behavior of these fascinating reptiles.”

Why the Solnhofen Limestone Is a Treasure Trove

The Solnhofen limestone deposits have long been a window into prehistoric life due to their unique mode of preservation. When ancient limestone layers split, they often reveal fossils flattened into two complementary slabs: one showing the bones, the other the body outline or impressions. Typically, these slabs are kept together as a single specimen.

But Sphenodraco’s two halves had taken divergent paths—one ending up in Frankfurt, the other in London, separated by geography and decades. Thanks to careful research and a bit of serendipity, these two halves have finally been reunited, allowing scientists to see the full picture for the first time.

Uncovering Evolutionary Secrets

Rhynchocephalians were once widespread, roaming alongside dinosaurs across continents during the Triassic and Jurassic periods. Today, the tuatara stands as the last living witness to this ancient lineage.

Discoveries like Sphenodraco help paleontologists understand how diverse and adaptable these reptiles once were. They reveal evolutionary experiments with different lifestyles — including climbing — long before modern lizards perfected the art.

This not only enriches our understanding of reptilian evolution but also illustrates how ecosystems of the past supported a complex web of life, with creatures occupying every niche from the forest floor to the treetops.

A Discovery That Bridges Time and Museums

The story of Sphenodraco scandentis is a reminder of how science can be a detective story spanning decades, continents, and institutions. It shows how museum collections, sometimes overlooked or forgotten, hold untold treasures awaiting rediscovery.

Victor Beccari’s finding underscores the importance of careful curation and the excitement that can come from revisiting old specimens with fresh eyes and new technologies.

As paleontology continues to piece together Earth’s distant past, the reunion of Sphenodraco’s fossil halves will stand as a shining example of how patience, collaboration, and curiosity can bring ancient worlds back to life — one stone slab at a time.

Reference: Victor Beccari et al, An arboreal rhynchocephalian from the Late Jurassic of Germany, and the importance of the appendicular skeleton for ecomorphology in lepidosaurs, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2025). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf073